|

Del Dios Gorge and Santa Fe Valley Trails |

|

A1

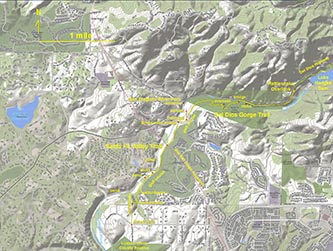

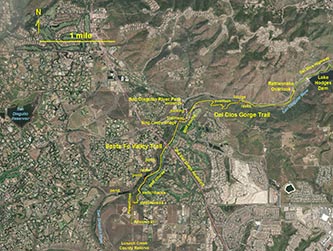

The Coast To Crest Trail associated with the San Dieguito River Parks runs through Del Dios Gorge and the Santa Fe Valley. Figure 1 shows where the trails field trip area is located in northern San Diego County.

A trailhead parking area is located at a off of the Del Dios Highway (Figure 2). The park entrance is next to the Paradise Produce Market (use caution, it is easy to miss while driving). There is limited parking that can fill on busy weekends (Figures 3 and 4). The trails are popular for both hikers and mountain bikes (so be careful!). The two trails start at the south end of the parking area drive (Figure 5) . The Del Dios Gorge Trail connects to the North Shore Trails around Lake Hodges about 2 miles to the east at the Rattlesnake Viewpoint. The Santa Fe Valley Trail follows the San Dieguito River valley to the west to a series of switchback that lead to the top of a mesa on the south side of the canyon.

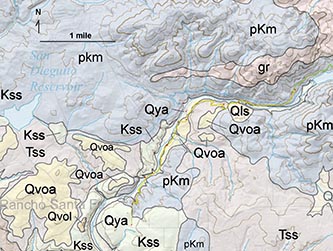

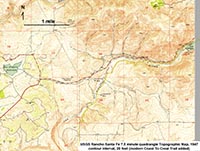

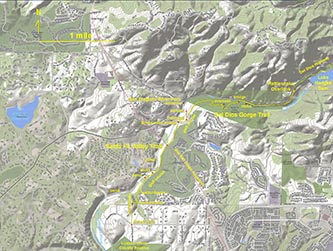

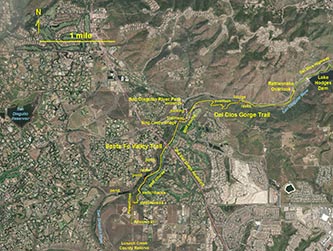

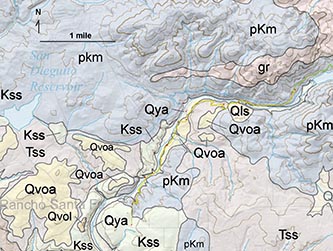

Figures 6 and 7 are maps that show the location of the trails with important reference features discussed in the image galleries below. Figure 8 is a generalized geologic map that shows the dominant bedrock in the the vicinity. Both sections of the Coast To Crest Trail are host to interesting and unique geologic features, wildlife habitats, and landscape features. The trails cross the transition between the coastal mountains of western Peninsular Ranges to the elevated coastal plain of northern San Diego County. |

Click on images for a

larger view. |

Fig. 1. Map of north western San Diego County showing the field trip study area.

|

Fig. 2. River Park entrance. |

Fig. 3. Trail parking sign. |

Fig. 4. Trail information kiosk. |

Fig. 5. Trailhead mileage sign. |

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 6. Topographic map of the trails area. |

Fig. 7. Satellite map of the trails area. |

Fig. 8. Geologic map of the trails area. |

Symbols on the Geologic Map

Qya - Quaternary, young alluvium - stream valley fill and floodplain deposits along the San Dieguito River (Santa Fe Valley).

Qvoa - Quaternary, very old alluvium - elevated stream terrace deposits and older coastal plain and elevated marine terrace deposits; 1-2 million years.

Qls and Qvol - Quaternary landslide deposits, recent and very old.

Tss - Tertiary sandstone and shale, mostly Eocene-age sedimentary rock formations of coastal and marine environments; 45-50 million years old.

Kss - Cretaceous sandstone and shale, mostly Late Cretaceous marine sandstone, shale, and conglomerate, about 70-90 million years old.

gr - Granitic rocks of Cretaceous-age associated with the Western Peninsular Ranges Batholith, intruded into older rocks about 100-90 million years ago.

pKm - Pre-Cretaceous metavolcanic rocks: lava flows, pyroclastic and volcanoclastic sedimentary deposits), mostly of Late Jurassic age. |

A2

Del Dios Gorge Trail

The parking area for the trails is located on the floodplain for the San Dieguito River (Figures 9 and 10). This environment has been significantly altered by the construction of Lake Hodges Dam. Before the dam, this area was probably covered with a sand and gravel bars scoured by seasonal floods. The dam cut off the sediment supply that used to flow through the canyon, ultimately supplying sediment to the coastline downstream. Areas that were probably exposed stream channels during dry seasons are now choked with dense vegetation, displacing and replacing habitats that probably once hosted a variety of different plant and animal species that we see today. Some areas of the floodplain are now covered with boulders and cobbles, mostly of basalt and granite composition derived from sources upstream. Nearly all the finer gravel, sand, and silt has been stripped away from the floodplain. The massive size of the boulders exposed on the floodplain are a testament of the massive size and intensity of floods that once moved these materials down the valley (Figures 11 and 12).

|

Fig. 9. View of parking area from Del Dios Gorge Trail. |

Fig. 10. San Dieguito River floodplain east of parking area. |

Fig. 11. Floodplain gravel bar and marsh near parking area. |

Fig. 12. Granite and basalt boulders on the floodplain. |

|

A3

Elevated Stream Terraces

From the trailhead parking area, the Del Dios Gorge Trail departs eastward along an elevated river terrace on the south side of the river canyon. There are actually multiple elevated stream terraces along the canyons and valleys of the San Dieguito River between the high peaks of the Peninsular Ranges and where it drains into the ocean.

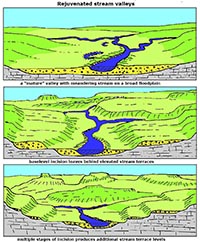

Base level is the lowest level to which a land surface can be reduced by the action of running water. It is typically equivalent to the lowest point a river or stream can reach entering the ocean or other large body of water. Base level of a stream entering the ocean will rise and fall with changes in sea level.

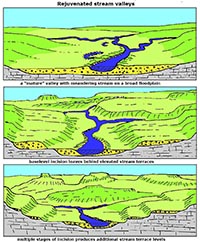

Figure 13 illustrates how stream terrace levels form over time. A stream terrace is one of a possible series of level surfaces on a stream valley flanking and parallel to a stream channel and above that marks the level of a floodplain in the geologic past. A change in stream gradient or stream flow can cause streams to carve into their floodplain, leaving a step like terrace along the side of the valley. Multiple events related to these changes can leave a series of step-like terraces (old floodplain surfaces) preserved along a stream valley. The erosional down cutting of a stream into its floodplain is called rejuvenation. |

Fig. 13. Formation of elevated stream terraces.

Fig. 13. Formation of elevated stream terraces.

|

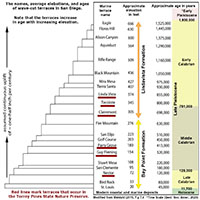

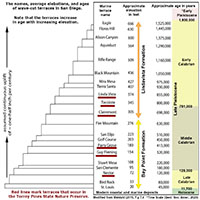

Once you can recognize the landscape features associated with elevated stream terraces, you can see them appearing as a series of steps going up the mountainsides. The lowest ones are easiest to see because because they are youngest and most recently formed. As they get older (and higher) on the sides of canyons erosion strips them away. Over time, erosion rounds off sharp boundaries, buries the terrace surfaces with sediments from above, and side streams carve canyons, cutting away older terrace deposits. The ages of the stream terraces in the Del Dios Gorge area is uncertain, but their origin is probably linked to climate cycles and sea level changes associated with the Quaternary ice ages and interglacial periods. Figure 14 compares the age and elevation of named elevated marine terraces on the San Diego coastal plain. How these ages correspond with inland stream terraces may be inferred.

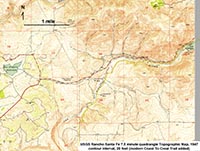

Figure 15 is the 1947 USGS topographic map with 20 foot elevation contours that reveal terrace level surfaces in the Del Dios Gorge area. Terraces appear as wider spaced contours in areas of less relief. Figures 16 to 18 shows the nearly level stream terrace surfaces along the Del Dios Gorge Trail. The two lower terraces are roughly 70 feet and 160 feet above the stream bed (possibly equivalent to the Nestor and Guy Fleming marine terraces). Figures 19 and 20 show terraces on the mountainside on the north side of the canyon.

The Del Dios Gorge Overlook is a good place to study the geology on the opposite side of the canyon (Figures 21 and 22). East of the overlook the terraces are not preserved and the trail descends into the canyon within the gorge below the dam. |

Diagram showing the step-like character of marine terraces with their names and elevations shown. Diagram showing the step-like character of marine terraces with their names and elevations shown.

Fig. 14. Age and elevation of named wave-cut marine terraces on the San Diego elevated coastal plains and mesas.

|

Fig. 15. 1947 topographic map shows terraces levels. |

Fig. 16. Elevated terraces on opposite side of the canyon. |

Fig. 17. Elevated Terrace along Del Dios Gorge Trail. |

Fig. 18. Del Dios Gorge Trail view looking east in spring. Fig. 18. Del Dios Gorge Trail view looking east in spring. |

Fig. 19. Elevated terrace above the Del Dios Highway. |

Fig. 20. Elevated terraces higher on the mountainside. |

Fig. 21. Side trail (to left) leads to a gorge overlook. |

Fig. 22. Overlook of the Del Dios Gorge. |

|

A4

Bedrock Geology of the Del Dios Gorge

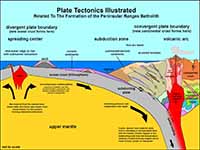

Within Del Dios Gorge there are two groups of rocks that make up the bedrock in the mountainsides. The oldest is labeled pKm on the geologic map; pKm stand for pre-Cretaceous metavolcanic rocks. This bedrock consists of ancient lava flows, pyroclastic eruption deposits (tuff or volcanic breccia), and volcanoclastic sedimentary deposits consisting of volcanic ash and rock fragments reworked and deposited on the seafloor. In the surrounding coastal mountains are called the Santiago Peak volcanics, named after rocks of similar age and composition studied on Santiago Peak in the northern Peninsular Ranges southeast of Los Angeles. of the same age ),. The rocks have been determined to be Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous age (about 160 to 120 Million years), however possibly older bedrock materials of Triassic and possibly older age are incorporated into these rocks in some locations nearby in the Lake Hodges and Del Dios Highlands areas, but not observed in the gorge. These rocks display varying degrees of metamorphic alteration.

The second group of rocks are labeled gr on the geologic map; gr stands for granitic rocks of the Western Belt of the Peninsular Ranges Batholith. These rocks formed from magmatic intrusions that melted their way into the older pKm rocks and solidified (crystallized) as massive igneous plutons far below the surface. These intrusive igneous rocks were determined to have formed in late-Early Cretaceous time, roughly 120 to 105 million years ago.

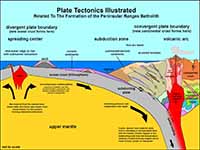

Both the pKm and gr rocks formed in association with volcanic arc associated with subduction zone settings (Figure 23). The older pKm probably formed as an volcanic island arc offshore with some of the rocks forming as submarine volcanoes in a similar setting comparable to the modern Aleutian Islands or Tonga volcanic arcs. The younger gr rocks formed in association with a volcanic arc batholith that developed along the western margin of the North American continent, similar to the modern Cascade Ranges in northern California to British Columbia, or the Andes volcanic mountains of South America. The Peninsular Ranges Batholith formed as part of the greater Cordilleran Ranges batholiths that developed along the west coast of North America during the Mesozoic Era including the batholith exposed throughout the core of the Sierra Nevada Range.

|

Fig. 23. Plate tectonics illustrated.

This model generally illustrates how the rocks of San Diego's Peninsular Ranges formed during the Mesozoic Era.

The pKm rocks represent rocks that formed in association with submarine volcanoes (originally formed at or near the surface). The younger gr rocks represent igneous plutons that formed deeper below the surface long after the pKm rocks were formed and deeply buried . |

| Fig. 24. Granitic Sill in Del Dios Gorge: This panoramic view is looking north across Del Dios Gorge from near the overlook area. A large sill of light-colored, cliff-forming granitic rock (gr) cuts horizontally across the upper part of the mountain. This feature is labeled gr on the geologic map (Figure 8). The granitic pluton forms a lens-shape body that appear to have injected horizontally into the pKm bedrock (older metavolcanic bedrock exposed throughout the gorge area). This massive sill is attached to the larger plutonic granitic body that underlies much of the Elfin Forest and Del Dios Highlands region to the northeast of the gorge. |

A5

Del Dios Gorge Bridge Area

The Del Dios Gorge Bridge is a pedestrian bridge over the San Dieguito River located about a mile east of the trailhead parking area (Figures 25 to 27).

Traveling east, the Del Dios Gorge trail descends off the stream terraces and crosses the river. The path then follows north side of the floodplain up to Lake Hodges Dam. Most of the riverbed is obscured by riparian growth (mostly willow) bordered by a mixed coastal sage scrub plant community (Figures 28 to 30).

Above the bridge, the river canyon narrows and the stream gradient steepens. Below the bridge the stream gradient is about 20 feet per mile. Above the bridge the stream gradient increases to about 60 feet per mile (up to the dam). Before the dam was constructed, floods must have raged through this section of the canyon. Several hundred feet north of the bridge is a small unmarked path that leads to a rocky section of the riverbed (Figures 31 to 36). From a geologic perspective is particularly interesting. Floods in the past have completely scoured the bedrock down creating a rugged riverbed typical of river with intense falls and rapids. The bedrock itself is polished and fluted. It consists of a very dark, dense, fine-crystalline metabasalt (basalt that has been metamorphosed, removing bubbles and lava-flow bedding structures). In contrast to the dark basaltic bedrock are the massive large light-colored granitic boulders scattered on the river bed that have been transported in from elsewhere. There are no significant silt, sand, and gravel deposits in this area.

|

Fig. 33. Massive granite boulders on the river bed. |

Fig. 34. Basalt outcrops and a falls plunge pool. |

Fig. 35. Small falls and a plunge pool. |

Fig. 36. Stream-polished basalt outcrop near stream. |

|

A6

Del Dios Gorge Trail From the Bridge To the Dam

East of the bridge, the Del Dios Gorge Trail gently ascends along

the north side of the river bed (Figures 37 to 39). Although this mile-long section of the trail is closer to the highway it is actually less impacted by highway noise because the sound is deflected away and above the trail in the canyon below.

Figure 40 shows a side canyon that enters the gorge from the south. East of that canyon, the trail passes through a large bend in the gorge. Steep slopes and cliffs line the south side of the canyon. Ravines (hour-glass canyons) cut into the slopes that rise 800-900 feet above the stream (Figures 41 to 45).

|

Fig. 37. Del Dios Gorge Trail between bridge and dam. Fig. 37. Del Dios Gorge Trail between bridge and dam. |

Fig. 38. Del Dios Gorge Trail between bridge and dam. |

Fig. 39. One-mile trail marker below the dam. |

Fig. 40. Canyon entering the gorge from the south side. |

Fig. 41. Del Dios Gorge south high wall, west of the dam. |

Fig. 42. Hour-glass-shaped ravines on gorge's south side. |

Fig. 43. Hour-glass-shaped ravines on gorge's south side. |

Fig. 44. Hour-glass-shaped ravines on gorge's south side. |

|

| Fig. 45. Panoramic view of Del Dios Gorge taken from the Del Dios Gorge Trail (Coast To Crest Trail) showing the river bed below the dam, the highlands with ravines on the south side of the gorge, to the side canyon coming in on the south (to the right). |

A7

Lake Hodges Dam

Figures 46 to 49 show views of Lake Hodges Dam. The Rattlesnake Overlook is located about 2 miles from the Del Dios Gorge parking area. From the Rattlesnake Overlook the Coast To Crest Trail continues along the north shore of Lake Hodges.

The San Dieguito River watershed is among the largest west of the divide in the Peninsular Ranges in San Diego County. During dry seasons and drought, the river is little more than a small stream. However, during periods of intense rainfall catastrophic flooding has cause widespread flooding along valleys in the coastal San Diego Region. Massive flooding events occurred in San Diego between Christmas of 1861 and January 1862. Other massive winter storms caused massive flooding 1891 and 1916.

Lake Hodges Dam was constructed in Del Dios Gorge in 1916 to provide flood protection and water supply for lands being developed by the Santa Fe Railroad in the lower San Dieguito River valley. The dam was purchased in 1925 by the City of San Diego and has been operated by city ever since (as described in Figure 4). The dam went through as second phase of construction and renovation in 1937 to reinforce the dam from potential earthquake damage.

Lake Hodges spillway is at 315 feet above sea level. It's maximum depth was 115 feet at maximum level. In 2019, the maximum water level of the reservoir has been reset to 295 feet to ensure the safety of the aging dam. The reservoir was designed to hold 33,550 acre-feet of water (about 10 billion gallons). The land surrounding the reservoir is now part of Lake Hodges Recreation Area, a part of the San Dieguito River Parks watershed protection lands. The Coast To Crest runs along the north shore of the reservoir |

Fig. 45. The trail intersects a restricted road t to the dam. |

Fig. 46. View of the dam from the Del Dios Gorge Trail. |

Fig. 47. Zoom view of Lake Hodges Dam. |

Fig. 48. Rattlesnake Overlook view of Lake Hodges Dam. |

|

A8

Examples of Rock Types in the Del Dios Gorge and Santa Fe Valley

All the bedrock the Del Dios Gorge is of igneous origin. The images below represent some of the varieties of rock types exposed in outcrops and boulders along the trails. The most of older pKm rocks throughout the gorge area consist of the extrusive volcanic rocks, basalt or andesite. Freshly exposed surfaces of basalt tends to have a dark gray to black, fine grained appearance (Figure 49). Andesite is a fine-grained volcanic rock and occurs locally in an , mostly medium gray or an assortment of colors, shades of purple, blue and green. Some local rocks are porphyry that contains larger crystals (phenocrysts) of feldspars or other minerals embedded in a fine-grained volcanic matrix (Figure 50). Some of the rocks are tuff (or volcanic breccia) formed from materials that were blasted out in volcanic eruptions and welded back together by residual heat (Figures 52 and 53). Most of these older rocks have endured some degree of metamorphism. The name greenstone applies to altered basalt and andesite containing green replacement minerals chlorite, epidote, and others (Figures 54 and 55).

The younger gr rocks intrusive igneous rocks that have a coarser crystalline granitic texture. Granitic rocks in the area include diorite, tonalite, and gabbro. Many of the local granitic rocks display an abundance of inclusions—fragments of the surrounding host rock that were trapped within the surrounding magma as it cooled (Figure 57 and 58). The dark inclusions in the granite (gr) are fragments of basalt and andesite from older pKm that shattered, broke off and sank into the magma as it forced into the host rock under great pressure.

Over the last 100 million years (after the pKm and gr rocks formed), the rocks have undergone a tremendous journey as plate-tectonic subduction ended and the western margin of North America split apart, forming the San Andreas Fault system and the opening of the Gulf of California. Over time, the region experience many thousand of strong earthquakes that shattered the rocks. Wherever the bedrock is exposed you can see fractures (Figure 59).In addition, tectonic uplift pushed up rocks that were once deep underground but are now exposed by surface weathering and erosion. Air and water react with minerals at or near the surface breaking them down, dissolving some or converting them to other minerals. Iron-rich minerals become clays or limonite, an iron-hydroxide mineral that gives soils a brownish color. Insoluble mineral grains get carried away as silt, sand, and gravel. Some of these materials are preserved as deposits on the ancient river terraces (Figures 60 and 61). Some of the gravel clasts tell an interesting story of their long journey along rivers starting in the highlands of Mexico to the coastline before the opening of the Gulf of California. Some of the durable cobbles are reworked from ancient shoreline beach gravel deposits along the coastline that existed in this region before the modern coastal mountains were uplifted to their current heights. |

Fig. 49. Basalt |

Fig. 50. Andesite porphyry |

Fig. 52. Andesite tuff. |

Fig. 53. Andesite tuff |

Fig. 54. Purple andesite with greenstone. |

Fig. 55. Greenstone with quartz hydrothermal veins. |

Fig. 56. Granitic rock (tonalite) with an inclusion. |

Fig. 57. Basalt inclusions in granitic rock. |

Fig. 58. Andesite inclusion in granitic rock. |

Fig. 59. Fractured and weathered bedrock. |

Fig. 60. Conglomeratic soil of a stream terrace deposit. |

Fig. 61. Stream terrace gravel deposits exposed along trail. |

|

A9

Santa Fe Valley Trail

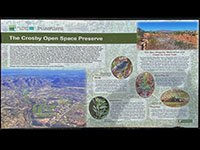

The Santa Fe Valley Trail starts at the San Dieguito River Parks parking area and extends westward for about 2 miles along the canyon of the San Dieguito River (Figures 62). This area, the Santa Fe Valley, has changed significantly over time. It was initially used for agricultural lands but is now being restored as protected watershed and a wildlife corridor. This well-maintained section of the trail cuts through the 170-acre Crosby Open Space Preserve west of Bing Crosby Boulevard (Figures 63 and 64). The open space preserve is a joint conservation effort between the County of San Diego, San Dieguito River Parks, Crosby-Rancho Santa Fe Home Owners Association, and the Rincon Consultants, Inc. Habitat Management Team. |

Fig. 62. Trailhead sign for the Santa Fe Valley Trail |

Fig. 63. Trail exhibit about the Crosby Open Space Preserve. |

Fig. 64. The trail near the Bing Cosby Boulevard bridge. |

Fig. 65. Santa Fe Valley near the trailhead parking area. |

Fig. 66. One of several bridges that cross small side streams. |

|

| Fig. 67. Panoramic view looking north and west across the broad Santa Fe Valley floodplain. The floodplain is gradually being restored to reflect native habitats, but only the removal of the dam might allow trapped sediments to fill in the valley to return it to it natural state. That is not likely to happen. Unfortunately, invasive species of plants and animals have impacted the setting and are likely here to stay without intensive conservation efforts. |

A10

Geology of the Elevated Coastal Plain in the Rancho Santa Fe Area

This section of the Coast To Crest Trail crosses the transition from the coastal mountain front of the Del Dios Highlands to the elevated coastal plain in the Rancho Santa Fe area. This transition expresses itself with the broader floodplain and lower hills along the Santa Fe Valley (Figures 67 to 69).

Figure 70 shows vertically tilted pkm strata on the north side of the river floodplain. These vertical layers are unconformably overlain by flat-lying sedimentary strata (poorly exposed but expressed as the gentle slope beneath the homes). This sedimentary strata is part of the Lusardi Formation of Late Cretaceous age (about 90 to 70 million years). The Lusardi Formation formed from boulders, cobbles, and sandy sediments deposited along the ancient coastline and offshore along the continental shelf margin. The Lusardi Formation is named after the formation's type area in the Lusardi Creek County Preserve (south of the Santa Fe Valley area). The Lusardi Formation pinches out along the mountain front and grows to about 400 feet thick in the type area around Lusardi Creek. The Lusardi Formation is labeled as Kss on the geologic map, Figure 9. The geologic map shows it locally cropping out along the west side of the Santa Fe Valley.

The Lusardi Formation is overlain by the La Jolla Formation (or La Jolla Group) of Eocene age (about 50 to 45 million years). Like the Lusardi Formation, the La Jolla Formation is thins out along the mountain front and thickens to hundreds of feet thick along the coastline. The La Jolla Group includes the Del Mar Formation, Torrey Sandstone, Scripps Formation exposed in the sea cliffs between La Jolla Cove to Carlsbad beaches (see description of these formations at Torrey Pines State Nature Preserve. The La Jolla Formation is labeled as Tss on the geologic map, Figure 9. The geologic map shows the La Jolla Formation cropping out along the on the hillsides east of the parking area throughout the Rancho Santa Fe area. |

| Figure 70 shows where the Santa Fe Trail passes a fenced area. It is here where the trail crosses the Second San Diego Aqueduct (buried beneath the gravel in this view). It is interesting to ponder how much more water flow though this underground pipeline than all the waters flowing in the local watersheds of San Diego! See the website: Where Does San Diego Get Its Water? |

A11

Rock Garden Area Along the Santa Fe Valley Trail

West of the fenced field near the Second San Diego Aqueduct, the Santa Fe Valley Trail enters an "important wildlife corridor" (Figure 72). About a mile from the trailhead parking area, the trail enters a scenic area informally named here the Rock Garden ( Figures 73 to 81). This is an area where the trail passes through a belt of large barren rocky outcrops and boulders on the river floodplain. During floods in the pre-Lake Hodges Dam era, this area must have hosted ragging rapids and falls. Today pools of standing water fill in gaps between rocky outcrops of pKm bedrock. Three small dams probably initial constructed as stock ponds and local water supply are now preserved for freshwater habitat for waterfowl and other wildlife. |

Fig. 72. Important wildlife corridor sign along trail. |

Fig. 73. Rock garden area along Santa Fe Valley Trail. |

Fig. 74. Rock garden along the Santa Fe Valley Trail. |

Fig. 75. Standing water between rocks along the trail. |

Fig. 76. Vertical fractures in the rock garden area. |

Fig. 77. Santa Fe Valley Trail in the rock garden area. |

Fig. 78. Outcrop of pKm rocks along the trail. |

Fig. 79. Important wildlife corridor sign along trail. |

|

| Fig. 80. Panoramic view of the east end of the rock garden area along the Santa Fe Valley Trail. |

| Fig. 81. Panoramic view of the west end of the rock garden area along the Santa Fe Valley Trail. |

A12

Switchbacks Area Along the Santa Fe Valley Trail

In the second mile of the Santa Fe Valley Trail beyond the rock garden area, the trail passes a couple ponds. The first is not easy to see from the trail because of the dense riparian foliage and a cattail marsh surrounding it.

Figure 82 shows an alluring outcrop next to the second pond along the trail. Signs say the pond is under 24 hour surveillance to keep out potential swimmers out of this sensitive wildlife habitat. The outcrop appears to consist of a stack of several lava flows that preserve columnar jointing patterns (typical fractures that form in lava flows as they pool and cool). The layers of these pKm rocks now dip steep to the west.

West of the pond the Santa Fe Trail beings a climb through a series of switchback, first up, down again, that back up again to the level top of the mesa in this part of Rancho Santa Fe.

Figures 83 to 95 show views along the Santa Fe Valley Trail in the vicinity of the switchbacks along the last mile of the trail. Some of the views show the character of the upland surface of the mesa (actually an erosionally dissected plateau) that owes its nearly level upper surface to that is was the seabed on the continental shelf as little as a couple million years ago. Through the last couple million years the San Diego coastline has been slowly rising, about 1/2 inch per century (probably in halts and starts associated with large earthquake adding to the mix). While this has been going on, sea level has been rising and falling with the passing ice ages—falling as continental ice sheets formed, and rising when the ice sheets melted. This resulted in the formation of the marine terraces (as illustrated in Figure 14).

|

Fig. 82. Pond with basalt cliff displaying columnar jointing. |

Fig. 83. Trail view with mesa below the switchbacks. |

Fig. 84. View of the fenced 1st set switchbacks. |

Fig. 85. View down the Santa Fe Valley with the 2rd pond. |

Fig. 86. View of the distant mountain front near the gorge. |

Fig. 87. Weathered basalt outcrop along the switchbacks. |

Fig. 88. Second set of switchbacks to top of mesa. |

Fig. 89. Zoom view east along the Santa Fe Valley Trail area. |

Fig. 91. Deeply weathered bedrock along the trail. |

Fig. 92. View looking back from the top of switchbacks. |

Fig. 93. View of the Santa Fe Valley from top of the mesa. |

Fig. 94. View of flat top of the mesa along power-lines road. |

|

| Fig. 95. Panoramic view that highlights the level surface of the erosionally dissected plateau (mesa) in the Rancho Santa Fe area. Step-like terraces are visible from the golf-course level to the top of the mesa on the right. Double Peak and the Del Dios Highlands near Elfin Forest are above the mountain front in the distance. |

A13

Selected Resources

Kennedy, M.P., and Moore, G.W., 1971, Stratigraphic relations of Upper Cretaceous and Eocene formations, San Diego coastal area, California: American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, v. 55, no. 5, p. 709-722.

Kennedy, M.P., Tan, S.S., Bovard, K.R., Alvarez, R.M., Watson, M.J., and Gutierrez, C.I., 2007, Geologic map of the Oceanside 30'x 60' Quadrangle, California California Geological Survey, Regional Geologic Map No. 2, 1:100,000 scale.

Nordstrom, C.E., 1970, Lusardi Formation; a post-batholithic Cretaceous conglomerate north of San Diego, California, IN Note and Discussion: Geological Society of America Bulletin, v. 81, no. 2, p. 601-606.

San Diego River Park: Preserving and interpreting the natural and cultural resources of the San Dieguito River Valley: Website (2021) with links to trail maps and information: http://www.sdrp.org/wordpress/trails/.

Todd, V.R., 1995, Geology of the Mount Laguna Quadrangle, California. U.S. geologicl Survey, Open-File Report 95-522, 34 p. (link). |

| https://gotbooks.miracosta.edu/fieldtrips/Del_Dios_Gorge/index.html |

7/20/2020 |

|

Diagram showing the step-like character of marine terraces with their names and elevations shown.

Diagram showing the step-like character of marine terraces with their names and elevations shown.