Elfin Forest Recreational Reserve and Vicinity |

|

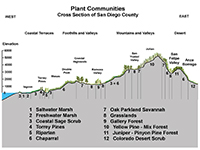

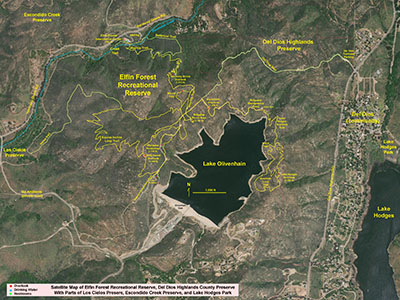

| Elfin Forest Recreational Reserve is one of the most popular hiking destinations in northern San Diego County (Figure 1). The Elfin Forest reserve is bounded on the north and east by the Del Dios Highlands County Preserve , a preserve located in the mountainous landscape south of Escondido and west of the community of Del Dios along the shore of Lake Hodges. The Elfin Forest reserve is bounded on west by the Escondido Creek Preserve and Los Cielos Preserve; both of these preserves are watershed and wildlife protection preserves located along the Escondido River and hillsides along San Elijo Canyon. The combined area of the reserve and preserves covers about 7 square miles of dominantly mountain chaparral and coastal sage scrub habitats in upland areas, and riparian forest (with oak, sycamore, and willow) and meadow grasslands along the valleys. |

Click on images for a larger view. |

Fig. 1. Satellite map of the Elfin Forest Recreational Reserve with trails and reservoirs. |

| Fig. 11. View looking upstream along Escondido Creek near the Elfin Forest Interpretive Center showing rapids and pools amid stream-side boulders and granite outcrops that are scoured by infrequent floods. |

| Fig. 12. View looking downstream near the Elfin Forest Interpretive Center showing rapids and clear-water pools typical of periods of low-water flow. |

Trails to the Elfin Forest HighlandsThere are 11 miles of trails available for hiking, mountain biking, and horseback riding. Everyone has to share the trails, and mountain bikers need to most especially cautious and courteous to hikers and horse riders. Sections of the trail are narrow and rocky, with blind turns, and rattlesnakes and other wildlife can be encountered on the trails at any time. Figure 13 is a map of named trails and destinations in the Elfin Forest Recreational Reserve. It is strongly recommended to bring a trail map with you. The Way Up Trail is the most used trail in the reserve—it links the main paring area with the trails in the highlands (Figure 14). Although there are trail marker signs along trails and at intersections, it is easy to get disoriented on trails in the highlands chaparral (Figure 15). Distances can be deceiving, and weather can change unexpectedly. Dehydration is a big problem during hot, dry weather. Pay close attention to the time that the reserve closes. Fines can be stiff for trespassing after hours or requiring reckless emergency assistance. Note that some of the trails connect with other trails in the surrounding preserves, and trails in those areas have different restrictions. For instance, Figure 16 shows a reserve boundary sign on the Horse Trail that connects to the Los Cielos Preserve. Some trails on the Los Cielos Preserve area are on private land requiring permission to access. For the safety of horseback riders, hikers, and wildlife (particularly rattlesnakes), mountain biking is discouraged on the narrow horse trails. |

| Fig. 18. Panoramic view of Olivenhain Reservoir and Dam from the hilltop on the west shore in Elfin Forest Recreational Reserve. Note that the reservoir is used for drinking water, so fishing, swimming, boating, or access to the shoreline, dam, or water pumping/treatment facilities are not permitted. |

| Fig. 24. Panoramic zoomed-in view from an overlook along the Lake Hodges Overlook Trail near the east end of Lake Hodges. Lake Hodges Park access road runs along the north shore of the lake. Bernardo Mountain (elevation 1,138 feet) is to the left at the far end of the Reservoir. Beyond Lake Hodges is Woodson Mountain (elevation 2,881 feet). To the left isthe peak of Starvation Mountain (elevation 2,103 feet), and in the distance beyond are the 3 high peaks of the Cuyamaca Mountains near Julian: North Peak (5,991 feet), Middle Peak (5,889 feet), and Cuyamaca Peak (6,493 feet). |

| Fig. 25. Panoramic wide-angle view of the Lake Hodges region from the Lake Hodges Overlook area. From this view the Del Dios Highway runs along the valley between the community of Del Dios and the mountain slopes within the Del Dios Highland County Preserve (that borders the Elfin Forest reserve along the ridgeline). The distant high peak to the right is Black Mountain (elevation 1,558 feet). |

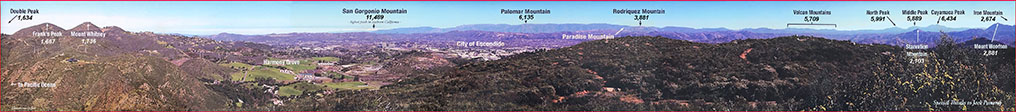

Escondido OverlookThe Escondido Overlook area is located along the Ridgeline Maintenance Road near the intersection with the Del Dios Trail that descended into the valley through the Del Dios Highlands County Preserve. The overlook provides views to the north and east that are different than the view from the Lake Hodges Overlook. Figure 26 is a panoramic view with features labeled. This is a partially restored version of the panoramic photo on a display panel at the Escondido Overlook picnic area. The elevations on this panel view have been revised to current USGS elevation data. |

| Fig. 26. A restored view of a panorama display at the Escondido Overlook located near the intersection of the Del Dios Trail that shows many of the named mountain peaks visible in the distance to the north and east on a clear day. (Click on images for a larger view.) |

The Botanical TrailOne of the best places to learn about local native plant communities is to walk the self-guided Botanical Trail (Figure 27). The 1.1 mile trail loop starts at the Elfin Forest Recreational Reserve parking area near the Interpretive Center. Note that the trail requires a relatively difficult, rocky creek crossing which should definitely not be attempted during high water (the trail will be closed, Figure 28). The Botanical Trail focuses on plants and ecology along Escondido Creek and the mountainsides of San Elijo Canyon (Figures 30 and 31). The Botanical Trail connects to the Way Up Trail that leads to the highlands of the reserve (Figure 32). Below are resources about the Botanical Trail.Botanical Trail Interactive Guide—This website includes an interactive map that provides information about 27 stop locations. Elfin Forest Botanical Trail Guide—Take this printout with you when you hike the trail; it has stop descriptions for 17 posted sign stops along the trail). Plants of the San Dieguito River Valley - This is a useful guide to many of the different common plants and habitats you can find in the coastal mountains and valleys of San Diego County. |

Fig. 27. Trail sign for the Botanical Trail. |

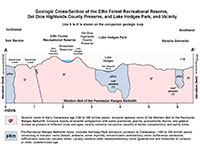

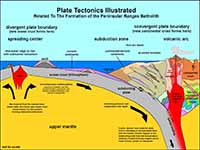

Geology of the Elfin Forest Recreational ReserveThe bedrock geology of the Elfin Forest Recreational Reserve is dominated by granitic rocks (mostly tonalite and diorite) that are locally exposed as outcrops or boulders on the mountainsides and along the trails (Figure 41).Figure 42 is a satellite map that shows the coastal mountains region around the Elfin Forest Recreational Reserve and Lake Hodges. Figure 43 is a geologic map of the same region that highlights the two dominant rock types in the region.

Figure 45 is a plate tectonics model showing a cross section of subduction zone associated with the formation of a volcanic arc. This model applies to similar volcanic islands chains around the world today, such the Aleutian Islands, Japan, Philippines, Tonga, or Andes Mountains. This model shows how the local rocks formed long ago during the Mesozoic Era. |

Fig. 41. Granitic cliffs along the Way Up Trail. Fig. 41. Granitic cliffs along the Way Up Trail. |

Bedrock GeologyTwo groups of rocks are found in the of the Elfin Forest Recreational Reserve illustrated on the map and cross section above: pKm (pre-Cretaceous metavolcanic rocks) and gr (Cretaceous granitic rocks).pKm (pre-Cretaceous metavolcanic rocks)The pKm rocks are exposed in a few locations in and around the reserve (including some places too small or not shown on the map above). The pKm rocks consist of volcanic rocks including lava flows, volcanic breccia or tuff (materials ejected from volcanoes), and sedimentary deposits made up of volcanic ash and other materials. Most of these rocks formed mostly during the Jurassic Period. However, some formed earlier (Triassic or older) and some fored later (actually in Early Cretaceous time). Because these rocks are older than other rocks discussed below, they have experience a longer geologic journey, and some have been metamorphosed by exposure to varying degrees of high heat and pressure. In San Diego County these rocks have been mapped and named Santiago Peak volcanics—named after Santiago Peak in the mountains south of Los Angeles where rocks of similar character and geologic age occur. Some of the pre-Cretaceous age metamorphic rocks (schist and gneiss) probably originally formed as ancient seafloor rocks that are are locally incorporated into theyounger pKm rocks. Research suggest the Santiago Peak volcanics formed in association with an ancient volcanic island arc system between 128 to 110 million years ago ((Herzig and Kimbrough, 2014). Figure 46 is an example of pKm rocks exposed in a road cut along Harmony Grove Road a couple hundred yards west of the entrance to the Elfin Forest parking area. These rocks have the appearance of layered lava flows and volcanic ash deposits similar to what you might see on a modern volcano, but these have be heavily compacted and chemically altered over geologic time. They may have accumulated on the side of an ancient underwater volcano. pKm rocks are well exposed in the highlands and peaks north of Elfin Forest in the Franks Peak and Double Peak Park areas (these links are to other field trip areas nearby with good exposure of pKm rocks). gr (Cretaceous granitic rocks)The gr rocks are granitic rocks that dominate the bedrock of the Elfin Forest Recreational Reserve. The peak of igneous activity in the western part of San Diego County region occurred in Early Cretaceous time, roughly 120 to 105 million years ago with the formation of the Western Belt of the Peninsular Ranges Batholith. A batholith consists of series of large igneous plutons that extend deep into the crust and have formed over time in association with an ancient volcanic arc. These granitic rocks are expressed as pink colors on the regional geologic map and cross section illustrated above.Figure 47 illustrates the massive and mostly homogeneous (non-layered) character of the granitic bedrock exposed in some locations throughout the reserve. Figure 48 show the same rock type, but where it is heavily fractured. Most of the granitic rock exposures in the area are heavily fracture. They have been shattered from perhaps many thousands of major earthquakes over many millions of years. They also have shattered from the gradual release of internal pressure from the removal of overburden pressure. Erosion has stripped away perhaps thousands of feet of old volcanic rocks and seafloor deposits that once covered the region long ago. As erosion gradually strips away weathered rock and soil, it leaves behind boulders that accumulate on the surface (Figure 49). |

Intrusive Igneous Rocks (Plutonic Rocks) in the Elfin Forest AreaThe gr rocks are plutonic rocks. These rocks formed within large bodies of molten rock that migrated upward from their sources deep in a subduction zone to where the eventually crystallized into rock, forming plutons. A pluton is a body of intrusive igneous rock. Bodies of molten material (magma) rise and cool deep below the surface where they are well insulated by the surrounding rocks. This gives the material more time cool and crystallize slowly, allowing larger, visible crystals to form. Perhaps the most common intrusive igneous rocks in San Diego's Peninsular Ranges is tonalite (or quartz diorite). |

What Happened After Cretaceous Igneous Activity EndedAbout 90 million years ago (in Late Cretaceous time), subduction and associated igneous activity along the West Coast ended (it continued farther to the east). The ancient coastal regions that was to become San Diego County was still attached to what is now northern Mexico. As time passed, the ranges of ancient volcanoes that covered the landscape completely wore down to a nearly level coastal plain with low relief (a peneplain). By about 45 million years ago (in Eocene time), higher sea levels relative the land allowed wave action to erode the coastline landward. Meanwhile, rivers draining from the Sonoran highlands region dumped sediments along the ancient continental shelf margin. These sediments are preserved as the sedimentary rock formations we see along the coastline such as at Torrey Pine State Nature Reserve.About 30 million years ago, the plate-tectonic scenario changed again, as North America moved westward over a spreading center. This lead to the rifting open of the Gulf of California and formation of the San Andreas fault system. The impact of these events are preserved on the landscape. Tectonic forces created numerous fault cutting across the San Diego region. An example of one cuts through the San Elijo Gorge near the Interpretation Center (Figure 54). Tectonic forces have uplifted the coastal region of San Diego and left behind high weathered erosion surfaces and elevated stream terraces. |

Fig. 54. Cliffs of granitic rock exposed in the mountainside of San Elijo Gorge near the Interpretation Center. The ravine lit up by sunlight to the left of the cliff is a fault trace (shown on map Figure 43). |

The Old Erosion Surface and Highland TerracesFigure 55 is a map of the physiographic regions of San Diego County. The Elfin Forest Recreational Reserve is located in a region known as the Area of High Terraces. The character of the this region can be easily seen from the high overlooks, such as at the Lake Hodges Overlook (see Figure 25). Looking off to the south and west it is easy to see that nearly all the mountain peaks on the horizon are within a limited elevation range. That is the Old Erosion Surface associated with the broad, relatively low peneplain surface that had developed by late Eocene to early Oligocenetime (45 to 30 million years ago). The coastline had eroded inland creating shallow embayments and broad coastal valleys. Since then, the land has steadily risen, and some of sediments deposited in those ancient embayments and flood plains are still locally preserved in scattered locations across the Highland Terraces landscape. The old erosion surfaces and small patches of ancient terrace terrace deposits are still partly preserved locally on the ridgeline/mesas within in the Elfin Forest and surounding higlands. |

Fig. 55. Map of Coastal Plain Terraces, High Terraces, and Old Erosion Surface regions. |

San Diego County's Slowly Rising Coastal Plain and MountainsStudies of the elevated marine terrace deposits along the San Diego coast suggest that coastline is slowly rising at a rate of about 0.5 inches per century. This uplift has been going on for millions of years and explains how the ridgelines/mesas we see today were once lowlands along a broad coastal plain. See the Torrey Pines geology fieldtrip section to learn more about elevated marine terraces along the coastline in San Diego County.Figure 56 shows an outcrop near the Escondido Overlook where wetting and drying over the millennia is slowly breaking down the granitic rock to produce sediments and soil. Circular patterns in the weather granite are called liesgang rings that are created as water seeps into the rock, dissolving some of the iron minerals, but as the rock dries out, it leaves behind a small circular pattern where evaporation leaves behind rust-like deposits (limonite) preserved in the pores of the rock. Figure 57 shows an even older weathered surface on a granite surface (revealed by its even brighter orange and red mineral coloration). This is an an ancient soil surface that preserves some fossilized desiccation cracks preserved in its surface. Figure 58 is an ancient sand deposit that has an abundance of small brown ironstone concreations weathering out. Figure 59 shows a concentrated deposit of ironstone concretions left behind where the sand eroded away. These deposits are nearly identical in character to the concretion-bearing sandstone deposits on elevated marine terraces of the Linda Vista Formation (on Torrey Pines Mesa), only these deposits are much higher and older. Learn more about similar Highland Terrace deposits nearby Frank Peak on the opposite side of San Elijo Gorge. |

Selected ResourcesFrost, B.R and Frost, C.D., 2008, A Geochmical Classification for Feldspathic Igneous Rocks: Journal of Petrology, v. 49, no. 11, p. 1955-1963.Herzig, C.T. and Kimbrough, D.L., 2014, Santiago Peak volcanics: Early Cretaceous arc volcanism of the western Peninsular Ranges batholith, southern California: in Peninsular Ranges Batholith, Baja California and Southern California; Morton, D. M. and Miller, F.K., editors, Geological Society of America Memoir v. 211. (web link) Kenedy, M.P., Tan, SS, Bovard, J.R., Alvarez, R.M, Watson, M.J., and Guiterrrez, C.I., 2007, Geologic map of theOceanside 30x60-minute quadrangle, California: California Geological Surve, Regional Geologic Map No. 2, map scale: 1:100,000. Miller, F.S., 1957, Petrology of the San Marcos Gabbro, Southern California: Bulletin of the Geological Society of America, V. 48, p 1397-1425. Le Bas, M.J. and Streckeisein, A.L, 1991, The IUGS ststematics of igneous rocks: Journal of the Geological Society, v. 148, no. 5, p. 825-833. U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Board on Geographic Names: Domestic Names [database search, 2020]: https://www.usgs.gov/core-science-systems/ngp/board-on-geographic-names/domestic-names |

| https://gotbooks.miracosta.edu/fieldtrips/Elfin_Forest/index.html | 12/14/2020 |