| Switch to: |

|

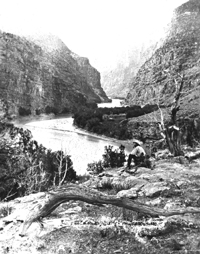

"Fantastic Rock," foot of Browns Park, Vermillion Creek. Colorado The Second Expedition (1871) took more time than the First (1869) to traverse the Green River section around the Uinta Mountains and through Dinosaur National Monument, taking time to explore side canyons, collect fossils, observe wildlife and plants, and photograph. By comparison to the First Expedition, the second trip through the region was relatively uneventful. In 1869, the expedition experienced loss of one of their boats loaded with supplies, a fire that nearly destroyed their supplies, and three of their crew who had abandoned the mission near its end were killed by Indians. The also faced the daily unknown terror of rapids and falls in potentially unescapable canyons in unexplored territory. |

|

Vermillion Creek drains into the Green River near the eastern end of the Uinta Range. John C. Fremont's expedition passed eastward through the Vermillion Valley in route to the mountain "park" valleys of Colorado in 1842. |

|

James C. Pilling in the Canyon of Lodore, Green River, just

within the entrance. Dinosaur National Monument. Moffat County, Colorado.

June 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital files: hjk00505 and hjk0505a Upon seeing the rapids at the entrance of an unnamed chasm of the Green River, a crew member of the First Expedition (1869), Andy Hall, recited part of a childhood poem that Major Powell knew well ("Cataract of Lodore" by Robert Southey, 1774-1843). Powell named Canyon of Lodore, after the poem. Canyon of Lodore is at the western end of Dinosaur National Monument. In 1909, paleontologist, Earl Douglass, made a spectacular discovery of dinosaur bone beds at the western end of Split Mountain. Initial excavations were conducted by the Carnegie Museum. Publicity led to the establishment of an 80-acre national monument in 1915. The monument was expanded in 1938 to preserve over 200,000 acres in Utah and Colorado. The modern park encompasses four major river canyons: Canyon of Lodore, Whirlpool Canyon, Split Mountain Canyon, and the Yampa River Canyon. The northern mouth of the canyon is called the Gate of Lodore where the Green River leaves the softer sedimentary and volcanic bedrock of Tertiary age and enters a canyon carved in more resistant and more ancient bedrock. |

|

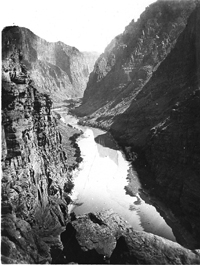

Canyon of Lodore, Green River. Dinosaur National Monument.

Moffat County, Colorado. 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital files: hjk00500 and hjk0500a The Canyon of Lodore cuts through an uplifted plateau, exposing strata of the Uinta Mountain Group (dense sandstone and quartzite of late Precambrian age, about 1 billion years old). Downstream the river canyon cuts through progressively younger strata including the Lodore Formation (Cambrian sandstone, about 525 to 505 million years old) and strata consisting of limestone, sandstone, and shale of late Paleozoic Age (about 350 to 250 million years old). The dinosaur-fossil bearing strata of Mesozoic age (250 to 65 million years old) crop out along the southern and western margins of this uplifted region and along the Yampa River (but not in the vicinity of Canyon of Lodore). The mountain ranges of the Rocky Mountain region (including the uplift of the Uinta Arch) occurred in multiple stages of Laramide Orogeny (roughly 70 to 20 million years ago), and uplift is still proceeding in the region. Younger sedimentary deposits derived from the surrounding Laramide uplifts cap many of the mesas and uplifted areas throughout the park region. |

|

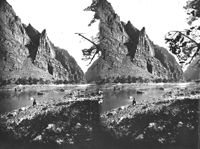

Heart of Lodore, Green River. Dinosaur National Monument. Moffat

County, Colorado. June 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00501 Today tamarisk (salt cedar) grows in abundance along the Colorado and Green Rivers. Tamarisk probably arrived in the southern Colorado River basin in the early 20th century and has since spread upstream to nearly all of the tributaries in Utah, crowding out many of the native species. |

|

The washed-out character of this image shows the difficulty of getting the right exposure. Experience and a trained eye were necessary for getting the right lighting of landscape features balanced with the right photographic exposure and processing. |

|

Note about anaglyphic images: the red color is associated with the left image, the cyan color is associated with the right. In this case the "left" side of plate was broken, causing the cyan to stand out where part of the plate is missing (both images were typically burned onto a single plate negative in the camera equipped with dual lenses). When red and cyan are combined in the images, the result is a gray-scale palette (white to black). The aged original photographs also had brownish tones that come through in many of the images. Unusual shaped patches of red or cyan color are usually imperfections in the original negative plates, either scratches or where the coating may of rubbed off or were perfectly prepared before exposure. Considering the time constrains, methods involved, and circumstances required to take and transport the glass plates, cameras, and photographs supplies, the survival of so many scenes is a reflection of the remarkable dedication to the photographic aspects of the expedition. |

|

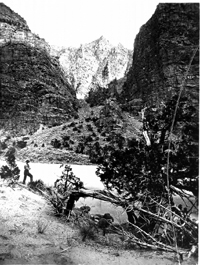

Canyon of Lodore, Green River. Dinosaur National Monument. Moffat County, Colorado. June 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00504 On the First Expedition (1869), crew member, George Bradley, noted that the Canyon of Lodore was practically one long series of rapids compared to the canyons upstream. |

|

Canyon of Lodore, Green River. Dinosaur National Monument. Moffat County, Colorado. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00539 |

|

Canyon of Lodore, Green River. Dinosaur National Monument. Moffat County, Colorado. June 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00562 |

|

View across Green River in Canyon of Lodore. Dinosaur National Monument. Moffat County, Colorado. June 1871. Negative cracked. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital files: hjk00571 and hjk0571a |

|

Green River in the Canyon of Lodore. Dinosaur National Monument. Moffat County, Colorado. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00575 |

|

|

|

Disaster Rapids in Canyon of Lodore, Green River. Dinosaur National Monument. Moffat County, Colorado. 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk0580a At Disaster Rapids, the river drops 35 feet through a 0.6 mile section of the canyon. |

|

Near view of The Haystack, Canyon of Lodore, Green River. Dinosaur National Monument. Moffat County, Colorado. June 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00588 |

|

Some of Powell's party in boats in Canyon of Lodore, Green River. Dinosaur National Monument Moffat County, Colorado. 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital files: hjk00590 and hjk0590a |

|

Canyon of Lodore, Green River. Dinosaur National Monument. Moffat County,

Colorado. 1871. |

|

Canyon of Lodore, Green River. Dinosaur National Monument. Moffat County, Colorado. June 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00601 |

|

Canyon of Lodore, Green River. Dinosaur National Monument.

Moffat County, Colorado. June 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00604 |

|

Canyon of Lodore, Green River. Dinosaur National Monument.

Moffat County, Colorado. June 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00610 |

|

Rapid at Canyon of Lodore, Green River. Head of Hell's Half

Mile. Jones, Hillers, and Dellenbaugh in the Emma Dean at foot of rapid.

Dinosaur National Monument. Moffat County, Colorado. June 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00612 |

|

Canyon of Lodore, Green River. Dinosaur National Monument.

Moffat County, Colorado. 1871. Photo by E. O. Beaman.

USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00628 |

|

Angel's Whisper, a side canyon of Lodore Canyon. Dinosaur National Monument.

Moffat County, Colorado. June 1871. |

|

Dunn's Cliff (2700 feet high), Canyon of Lodore, Green river.

Dinosaur National Monument. Moffat County, Colorado. June 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00620 Dunn's Cliff is named in honor of one of the men reported to have been killed by Indians near the end of Powell's First Expedition in 1869. |

|

Nearer view of Dunn's Cliff, Canyon of Lodore, Green River.

Dinosaur National Monument. Moffat County, Colorado. June 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00621 Most of the cliffs in the Canyon of Lodore are sandstones of the Precambrian Uinta Mountain Group. However, sedimentary rocks of Cambrian and Mississippian age crop out along the upper part of Dunn's Cliff (the light-colored upper portion of this view). The Lodgepole Limestone (Mississippian) forms the top of the cliff. Juniper and pinyon-pine forests grow on the the slopes and crevasses throughout the mountainsides. |

|

Bruce R. Julian (USGS), however, has identified the location as Warm Springs rapid on the Yampa River. Hillers and others did go on frequent scouting mission throughout the voyage. Bruce wrote: "This picture is particularly

important because it was the site of a major (~1000 year) flash

flood/debris flow on June 10, 1965. I know because I was there, and

was nearly killed. (The next day a professional boatman WAS killed by

the rapid.)" |

|

Echo Park, looking down from upper end. Yampa River in the

foreground. Green River enters from the right. Dinosaur National Monument.

Moffat County, Colorado. 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00645 Echo Park is a wide bottom at the confluence of the Green and Yampa rivers. Cliffs along this section of the canyon consist of Weber Sandstone (Pennsylvanian and Permian age). Powell named the area for the tremendous echoes his crew could produce off the cliffs. Members of the First Expedition had already been to down the Yampa River valley. After the trials of the Canyon of Lodore the expedition's morale was improved knowing that they were camping in a familiar location. Downstream of Echo Park, the Green River enters Whirlpool Canyon. |

|

Echo Park from upper end. Yampa River in foreground coming from the left. Green River enters from the right. Dinosaur National Monument. Moffat County, Colorado. July 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00600 |

|

Island Park, Green River. Dinosaur National Monument. Uintah

County, Utah. July 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00681 At the downstream end of Whirlpool Canyon, the bedrock changes from Paleozoic age to Mesozoic age. Cliffs of cross-bedded sandstone of the Glen Canyon Formation (Late Triassic to Early Jurassic) crop out around the broad cove at Island Park. |

|

Island Park, Green River. Dinosaur National Monument. Uintah

County, Utah. July 1871 (Photo by E. O. Beaman) USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00684 |

|

View from small cave in Split Mountain Canyon, Green River. Dinosaur National Monument. Moffat County, Colorado. July 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00545 |

|

General view of Green River in Split Mountain Canyon from

above (3000 feet) at entrance. Looking downstream. Dinosaur National Monument.

Uintah County, Utah. July 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00687 |

|

Green River. Split Mountain Canyon. Not far from entrance

to canyons. Dinosaur National Monument. Uintah County, Utah. July 10, 1871.

USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00690 The Green River cuts through a great anticlinal structure at Split Mountain, exposing rocks of Paleozoic age. |

|

Boats on Green River in Split Mountain Canyon. Dinosaur National

Monument. Uintah County, Utah. 1871. Negative broken.

USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00698 |

|

Cliffs of Weber Sandstone (Pennsylvanian and Permian age) form the canyon rim throughout the Split Mountain. |

|

Split Mountain. Dinosaur National Monument. Uintah County, Utah. This view looking downstream toward the lower canyon where cliffs of Weber Sandstone (Pennsylvanian and Permian age) crop out high on the mountainsides. Downstream of the lower gorge the Green River crosses through hogbacks of steeply dipping strata of Mesozoic age that crop out along the south side of the Split Mountain anticline. |

|

Mouth of Ashley Creek. Uintah County, Utah. July 4, 1871. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00672 Ashley Creek is about 21 miles downstream of the lower end of Split Canyon (about 13 miles south of the park). Ashley Creek enters the Green River from the west. These photos are probably a section of the stream where the creek carves a canyon in Late Cretaceous Mesaverde Sandstone. |

|

"Twin Pinnacles," on Ashley Creek, Green River.

Uintah County, Utah. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00489 |

|

Rock Pinnacle on Ashley Fork. Uintah County, Utah. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00490 |

|

Rocky gorge of Brush Creek, on Ashley Fork, Green River. Uintah County, Utah. USGS Earth Science Photographic Archive digital file: hjk00491 |

|

Rocky gorge of Brush Creek, on Ashley Fork, Green River. Uintah County,

Utah. On the First Expedition (1869), Powell's party camped near the mouth of Ashley Creek while the Major's boat proceeded downstream to the Uintah [Duchense] River -- the next tributary to the south where a overland route between Denver and Salt Lake City crosses the Green River. At the crossroads, Powell and his companions continued 40 miles west to the Uintah Ute Agency to collect and send mail, ship fossils, and purchase more food for the journey. The remaining men trailed behind hunting, fishing, and exploring the river valley, waiting for the Major's return near the confluence of the Duchense and Green Rivers. They reported having had a miserable experience dealing with mosquitoes waiting for Powell's return a week later. They then departed downstream into uncharted territory along the Green River: the Desolation Canyon wilderness. On the Second Expedition (1871) Powell left at Ashley Creek to be with

his child-bearing wife, Emma, in Salt Lake City and to troubleshoot problems

for the rest of the journey. Powell turned the command over to his brother-in-law

"Prof" Almon Harris "Harry" Thompson to lead the expedition

downstream. Powell rejoined the Second Expedition in at "Gunnison

Crossing" (Green River, Utah) on September 3rd. |