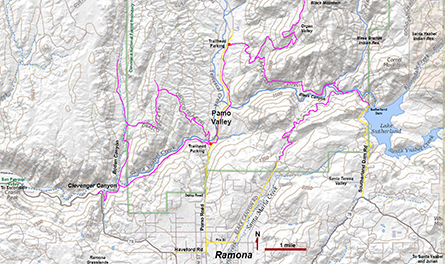

Pamo Valley part of the vast watershed/open space/ecological protection region north of Ramona in central San Diego County. The valley is drained by Santa Ysabel Creek, one of the headwater tributaries of the San Dieguito River. Much of the area is part of the Cleveland National Forest. This impressively scenic rural valley (or canyon) is surrounded by the high mountainous plateaus (or mesas) and ranges in the core or the Peninsular Ranges (map, Figure 1).

Pamo Valley is host to a section of the Coast to Crest Trail system (managed by the San Dieguito River Park. The Trailhead Parking is located on Pamo Road (about 3 miles north of downtown Ramona). The lower Pamo Valley Trail begins at the trailhead parking area and links to other trails to the west including the Orasco Truck Trail (loop) and Boden Canyon Trail. The Boden Canyon Trail provides access to lands to the east and north managed by the Boden Canyon Ecological Reserve. The upper Pamo Valley Trail also starts at the trailhead parking area and connects to a trail system including the Black Mountain Trail, the Santa Ysabel Truck Trail, and Black Canyon Trail, and Lake Sutherland (a reservoir/park for the City of San Diego).

|

Click on images for a larger view.

|

Figure 1. A map of Pamo Vally near Ramona, California.

Figure 1. A map of Pamo Vally near Ramona, California. |

Pamo Valley is accessible from Ramona via Pamo Road. Travelling north, Pamo Road crosses a couple miles of the broad upland valley that surrounds the town of Ramona. The broad upland is also host to the Ramona Grasslands County Preserve. Driving north along Pamo Road, the road suddenly drops down a relatively steep descent of about 1,000 feet in one mile down into Pamo Valley. The geologic map of San Diego County show that the linear valley (Pamo Valley) carved by stream erosion follows the trace of an old fault zone (Figure 2).

A large trailhead parking area next to Pamo Road on the left at the base of the hill (about 3 miles from downtown Ramona). There are two trails starting at the parking area. The upper Pamo Valley Trail follows the valley northward a couple miles to another trailhead parking area for the Black Mountain Trail system (Figure 3). The lower Pamo Valley Trail follows the Santa Ysabel Creek canyon southward to where it connects with the Orasco Truck Trail (loop) and the Boden Canyon Trail, and trails in the Clevenger Canyon area (Figure 4). The lower Pamo Valley Trail is a more shady path that cuts through oak forest and sycamore riparian forests (Figure 5).

|

Fig. 2. View north along Pamo Road toward Pamo Valley. Santa Ysabel Creek carved a linear valley along an old fault. |

Fig. 3. This sign with trails and park rules is posted near the trailhead parking area off of Pamo Road. |

Fig. 4. This is a gate on the Pamo Valley Trail that leads west into Clevenger Canyon and Boden Canyon areas. |

Fig. 5. View looking east at the oak and sycamore forest that covers the floodplain of Santa Ysabel Creek. |

|

Santa Ysabel Creek is part of the greater San Dieguito River watershed (Figure 6). It extends from headwaters in Volcan Mountain area near Julian downstream into the San Pasqual Valley near Escondido, where it merges with Santa Maria Creek to become the San Dieguito River (near the San Diego Zoo Safari Park in San Pasqual Valley).

East of the Volcan Mountain area, Santa Ysabel Creek drains through the Santa Ysabel upland valley near the town and indian reservation that share the name. Continuing downstream it cuts through an incised canyon on Mesa Grande before draining into Lake Sutherland (see map, Figure 1). Construction on Sutherland Dam started in 1927, but it was not completed until 1954. When the reservoir is full, it has a water storage capacity of 29,508 acre feet; the lake covers 556.8 acres, has a maximum water depth of 145 feet, and has 5.25 miles of shoreline.

Below

Sutherland Reservoir, Santa Ysabel Creek drains through Black Canyon for several miles before draining into the the broad upper part of Pamo Valley (Figure 7). The controlled flow from Sutherland Reservoir moderates the discharge into the stream and moderates flooding. Much of the flow sinks into the aquifer storage beneath Pamo Valley before discharging again into the stream before flowing through Clevenger Canyon into San Pasqual Valley (Figures 8-10). |

Figure 6. Watershed basins of San Diego County.

Figure 6. Watershed basins of San Diego County. |

Fig. 7. Wild turkeys graze in open grasslands (former hay fields, now watershed) in upper Pamo Valley floodplain.

Fig. 7. Wild turkeys graze in open grasslands (former hay fields, now watershed) in upper Pamo Valley floodplain.

|

Fig. 8. Low summer flow in Santa Ysabel Creek in the summer replenishes the aquifer beneath the valley. |

Fig. 9. View of the dry, sandy stream bed of Santa Ysabel Creek in the summer in Pamo Valley (near the trailhead). |

Fig. 10. View looking west from Pamo Valley Trail about 2 miles east of the trailhead showing Clevenger Canyon. |

|

| Parts of Pamo Valley is leased by the City of San Diego to an active cattle grazing operation. Despite the cattle, the valley is host to abundant wildlife that utilize the variety of habitats including the riparian sycamore and willow forest along the stream, the oak forests and grasslands throughout the valley, and the along the chaparral-covered mountain slopes (Figures 11-14). Wildlife frequently seen in the valley include mule deer, coyote, bobcat, many kinds of raptors (including golden eagle), and many types of songbirds, rodents, lizards, frogs and toads. |

Fig. 11. Sycamore and willow riparian forest along Santa Ysabel Creek. |

Fig. 12. Live oak forest and grassland habitat along the lower Pamo Valley Trail. |

Fig. 13. One of many large live oaks along the lower Pamo Valley Trail. |

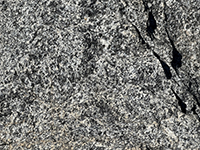

Fig. 14. Granitic bedrock exposed in outcrops along the lower Pamo Valley Trail. |

|

| The mountainous region around Pamo Valley is within a physiographic region called the Area of the "Old Erosion Surface" and is part of the Santa Ana Tectonic Block (Figure 15). Remnants of this old erosion surface are partly preserved as the rolling uplands of the surrounding plateaus and mesas (like nearby Mesa Grande). During Miocene time while the San Andreas Fault was developing along with the opening of the Gulf of California, the region around Ramona was a low rolling coastal plain and interior lowlands plateaus. Since middle Miocene time (about 10 million years ago) the landscape has slowly risen, nearly a couple thousand feet as the modern Peninsular Ranges began to rise. Streams like Santa Ysabel Creek carved downward, cutting into to ancient crystalline basement rocks that had formed much earlier in the late Mesozoic Era. These crystalline rocks formed before about 90 million years ago deep beneath a great volcanic arc. The volcanic arc was part of the ancestral Cordilleran Mountain chain that ran along the West Coast from southern Mexico to Alaska. These ancient mountains eroded away long ago, long before the later uplift of the modern Peninsular Ranges. |

Fig. 15. Physiographic map of San Diego County. |

| Bedrock Geology: The ancient crystalline bedrock is exposed as barren rocky outcrops and boulders on the mountain slopes. These rocks preserve characteristics of the ancient igneous plutons associated with the Peninsular Ranges batholith. Some of the exposures preserve aspects long geologic history of igneous intrusion, faulting, and metamorphism. Figure 16 is an outcrop of complexly altered granite and gneiss cross-cut by smaller dikes and intrusions (a migmatite). Figures 17 and 18 show outcrops of banded gneiss exposed along the lower Pamo Valley Trail. Figure 19 is a closer view of an outcrop of the coarse crystalline gabbro. |

Fig. 16. Complexly altered granite and gneiss (migmatite) exposed along Pamo Road. |

Fig. 17. Granitic gneiss bedrock outcrop along the lower Pamo Valley Trail. |

Fig. 18. Banded gneiss outcrop along the lower Pamo Valley Trail. |

Fig. 19. Coarse crystalline gabbro outcrop exposure along the lower Pamo Valley Trail. |

|

| Fig. 20. This panoramic view is looking north along the lower Pamo Valley Trail showing the forested valley and the chaparral-covered mountainsides. The rolling skyline partly reveals the character of the deeply erosionally dissected plateau and highlands of the Area of the "Old Erosion Surface." |

https://gotbooks.miracosta.edu/fieldtrips/Pamo_Valley/index.html

|

5/26/2022 |

|