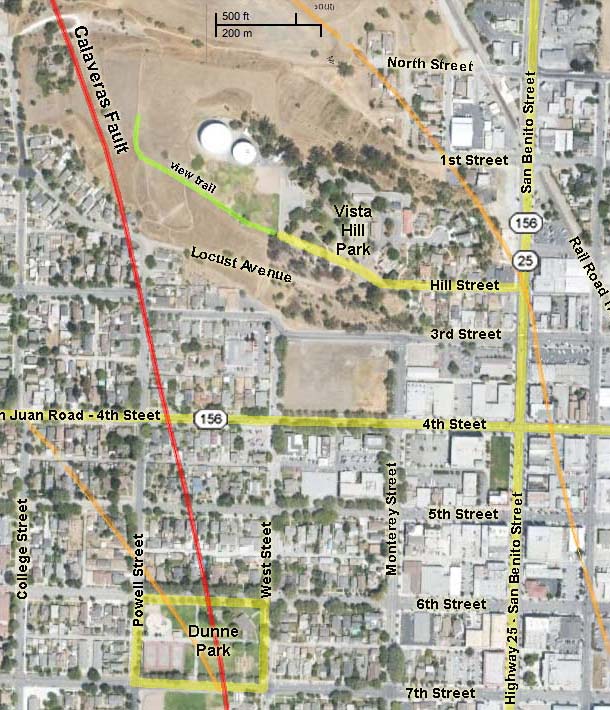

Calaveras Fault in Hollister, California

|

|

Field Trip Overview

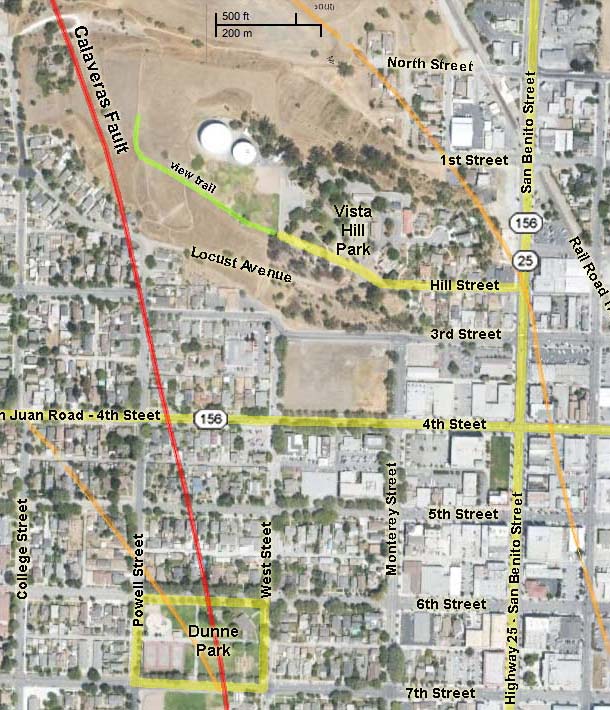

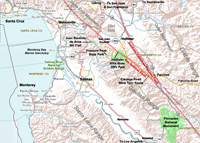

Downtown Hollister is one of the most important geology field trip destinations in the United States, and for good reason. Hollister is one of three towns in California that declares itself "the Earthquake Capital of the World" (a claim shared with Coalinga and Parkfield). The town of Hollister was built directly on the highly geologically active Calaveras Fault, a strand of the greater San Andreas Fault system. Field trip destinations include Stop 1: a walk around a scenic overlook of region from Vista Hill Park, and Stop 2: a visit to the actively seismic creeping trace of the Calaveras Fault in Dunne Park (between 6th and 7th Streets in a suburban neighborhood near downtown. Other field trip destinations nearby include San Juan Bautista, Fremont Peak State Park, the San Andreas Fault in Cienega Valley, and Pinnacles National Park.

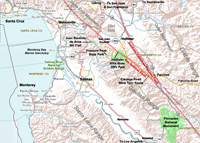

History of Hollister region: The city of Hollister is located in Hollister Valley, a broad lowland basin at the southern end of the greater Santa Clara Valley that extends northward to southern San Francisco Bay. Hollister Valley is surrounded by coastal mountains including the Gavilan Range to the southwest, the Quien Sabe Range (part of the greater Diablo Range) to the east, and the Lomerias Muertas (or Flint Hills) and the more distant Santa Cruz Mountains to the northwest. The city was built on the elevated river terraces of the San Benito River floodplain.

Prior to the establishment of Mission San Juan Bautista, the land in the region was inhabited by the Amah Mutsun Ohlone Indians. Small communities were scattered along the elevated river terraces along the San Benito and Pajaro rivers. With the establishment of the mission in 1797, the Mutson and other indians in the region were subjugated into service with the arrival of the Spanish/Mexican settlers in the early 1800s, and all the land was subdivided into ranchos and homesteads. The California missions were secularized in 1834 when California separated from Spanish control.

|

|

| Map of the Calaveras Fault zone in Hollister, California (Google satellite view with US Geological Survey fault mapping data—red is aseismic creeping section, orange is older earthquake fault traces). |

U.S. Army exploration party lead by John C. Fremont passed through the area in 1847 and had a nearly disastrous encounter with troops under the Commandante General of the Mexican army, José Antonio Castro. Fremont's crew had climbed nearby Gavilan Peak and had planted a flag for the United States, but decided to flee when the odds of surviving a military encounter didn't appear in their favor. Fremont and his crew continued to Sutter's Fort and Sacramento where they organized a revolt and declared the region as the Bear Flag Republic. The California Gold Rush of 1849 began a flood of non-Spanish speaking people into the region. With the overwhelming surge of immigrants, the republic became the state of California on September 9th, 1850.

The town of Hollister was founded on November 19,1868 when land was sold by the owner of the property—William Hollister. At the time, the area was still part of Monterey County. Southern Pacific Railroad began train service to Hollister on July 13, 1871. As the population grew, the City of Hollister was incorporated in August 29, 1872. The local population voted to split from Monterey County in 1874, and Hollister became the county seat of San Benito County. With access to the railroad, the regional wealth grew, providing agricultural products to the growing cities and ports around San Francisco Bay. The region's primary export was hay and cattle, but expanded into a rich variety of agricultural products and limited industry, and home to a growing commuter and retirement community. The 2010 U.S. census population of Hollister was 34,928.

|

Geologic Setting: The town of Hollister has a very interesting geologic setting. The town is built on the valley floor of the southern end of the greater Santa Clara Valley that extends northwestward to southern San Francisco Bay (between the Santa Cruz Mountains to the northwest and the Diablo Range to the east). The Quien Sabe Range to the east is a portion of the greater Diablo Range that encompasses a rugged mountainous area—remnants of an ancient volcanic field, along the eastern side of Hollister Valley. The low hills to the south and west of Hollister are called the Hollister Hills, which are foothills to the higher Gavilan Range to the southeast.

The city of Hollister was built across the fault line traces of the Calaveras Fault zone. The San Andreas Fault runs along the southern side of the San Juan Valley and crosses through the Hollister Hills along the northeastern flank of the Gavilan Range. The Sargent Fault zone runs through the Lomerias Muertas (Spanish for "barren hills"—these were also named the Flint Hills, a family name, not named for the rock flint). The Sargent, Calaveras, and San Andreas fault converge southward into the San Benito River Valley in the region south of Hollister and Pinnacles National Park. Other faults in the region include the Quien Sabe and Tres Pinos fault zones in the hills south and east of Hollister. The Quien Sabe Fault runs along the eastern mountain front of the Quien Sabe Range (see the geologic map). Movement along these faults are largely responsible for the shape of the landscape, with movement pushing up the hills and mountains while the Hollister and San Juan valleys are sinking and filling with alluvial sediments.

Both the Hollister and San Juan Valleys have been filled with shallow lakes during cooler and wetter periods in the recent geologic past (during and shortly after the last ice age that ended about 15,000 years ago). Ancient Lake San Benito proceeded the small Ancient Lake San Juan. Step-like terraces along flanks of the Lomerias Muertas and along the river valley record the progress of changing stages of valley filling and erosional downcutting though the major wet to dry periods during the Quaternary Period. These terraces also reveal aspects of the gradual uplift and warping of the hills and mountain ranges along the regional fault system.

By the time of the arrival of the Spanish ephemeral wetlands and marshes spread throughout the low areas around Hollister and San Juan valleys along the San Benito River and other shifting drainages. The gradually shifting faults played a roll in controlling stream migration and capture. At different times in the geologic past rivers drained northward into San Francisco Bay, through the San Juan Valley, and through the gap drained by the modern Pajaro River between Gilroy and western San Juan Valley. South of Hollister fault motion caused changes to the drainage patterns of Tres Pinos Creek and the San Benito River. In the past, the primary drainage was through a gap between the Ridgemark hills along the Highway 25. Today the two streams cut through canyons before merging as near the vicinity of Southside and Union Roads a couple miles south of Hollister.

|

Click on maps and photos for larger views. |

|

| California's Central Coast regional topographic map including the Hollister area |

|

| Geologic Map of the Hollister region (modified from California Geological Survey, Monterey 1:100,000 scale map, 20022) |

| |

Field Trip Destinations

Stop 1—Vista Hill Park: This small park is located on a small hill top that provides exceptional views of the surrounding region. Park Street intersects San Benito Street (Highway 25) on the west side of the street between 1st and 2nd Streets (a block south of the Taco Bell on San Benito Street—pay attention when driving in that the street entrance is easy to miss!). Follow Park Street to the hilltop and park next to the playing field. The hilltop view to the south overlooks downtown Hollister and the original older suburban part of Hollister (see Stop 2 below). Beyond the urban area to the south is a linear hill in the vicinity of the Ridgemark neighborhood. The small ridge is bounded on either side by strands of the Calaveras Fault. To the right of the hill is the canyon of the San Benito River near its confluence with Tres Pinos Creek. To the left of the Ridgemark ridge is a water gap that used to be the valley of primary drainage from the south. The low, now dry, gap was used for the Union Pacific Railroad line to its terminal destination in Tres Pinos about 6 miles south of downtown Hollister.

The best views are along a trail that follows the ball field fence out into the fields on the hilltop to a vista point at the west end of the hilltop (see panorama below. The sweeping view ranges from the high peaks of the Quien Sabe Range to the east, the Santa Clara Valley to the north, the Lomerias Muertas ("barren hills") and Santa Cruz Mountains to the northwest, the San Juan Valley to the west, and the northern end of the Gavilan Range with Fremont Peak to the southwest.

|

|

|

| Entrance to Vista Hill Park, a hilltop park near downtown Hollister |

View of Ridgemark Ridge and the valley south of downtown Hollister |

|

|

| View looking south along Powell Street toward McHarlan Peak in the Gavilan Range (see map above). |

Zoomed-in view of McHarlan Peak and the Hollister Hills (low foothills on the north side of the San Andreas Fault) |

Panorama view from Vista Hill Park in Hollister, California showing the regional landscape features (click on image for larger view).

|

The Calaveras Fault: It is possible to walk down Locust Street from Vista Hill Park and walk through the neighborhood to examine the structural damage to streets, curbs, walls, and buildings that are slowly being deformed, warped, or broken by the slow creeping motion of the Calaveras Fault. In Hollister the Calaveras Fault is displaying aseismic motion—one side of the fault is slipping past the other side of the fault slowly without earthquakes. The fault is moving on average a little less that a centimeter a year. The US Geological Survey has been measuring the rate of movement of the slip for decades. The rate of measurable movement varies slightly from year to year and from one location to another. The most rapid slip rates measured was about 15 millimeters per year in the period between 1961 and 1967. It has slowed to just under 7 millimeters per year.

Whereas it is possible to go street-to-street to examine the damage along the trace of the fault, please be aware that many sites of the visible damage are on private property or in alleyways behind homes. Residents are very aware of the fault trace and are rightly concerned about out-of-towners peaking around their neighborhood. They deal with field trip groups and classes on a regular basis. Although most are good natured about it, some may be otherwise. It is recommended here to go directly to the best visually interesting site to see the fault in and around Dunne Park.

|

Stop 2—Dunne Park: Dunne Park is located between 6th and 7th Streets (north and south) and West and Powell Streets (east and west). There is ample parking around the park. Midway between West and Powell Streets is a gentle slope that represents the weathered scarp of the Calaveras Fault. On either side of the park it is possible to observe the offset walls, sidewalk, street curbs, and fractures in the street pavement. Repairs to the concrete and asphalt are relatively short lived.

Although the Calaveras Fault is slipping at the surface, how it is behaving at depth is uncertain. Earthquake data shows that small earthquakes are occurring along the fault and other faults in the region on a nearly daily basis—most are to small to feel. However, Hollister has experienced many damaging earthquake. Large ones affected the region in 1868, The largest (modern) earthquake within 100 miles of Hollister, California was the 6.9 magnitude Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989. Other strong earthquakes in the area recorded by the USGS were a 5.7 and 5.5 in 1988, 5.7 in 1986, 5.7 in 1979. Many moderate earthquakes (below magnitude 5.5) have been recorded in the region.

The USGS earthquake hazard estimates suggest that there is an almost 100 percent chance of a major earthquake within 50 kilometers of Hollister, California within the next 50 years. |

|

|

| Offset curb on 6th Street caused by aseismic creep on the Calaveras Fault |

Offset wall and sidewalk on 6th Street across from Dunne Park. |

| |

| |

Selected References

City of Hollister website: http://www.hollister.ca.gov/site/index.asp

Drinkwater, J.L., Sorg, D.H., and Russell, P.C., 1992, Geologic map showing ages and mineralization of the Quien Sabe volcanics, Mariposa Peak Quadrangle, West-central California: USGS Miscellaneous Field Studies Map- 2200.

Rogers, T. H. and Nason, R. D., 1971, Active fault displacement on the Calaveras fault zone at Hollister, California, Seism. Soc. Am. Bull., 61, 399-416.

Schweitzer, P., [2012], Tertiary volcanic flow rocks, unit 1 (Quien Sabe-Burdell Mountain): U.S. Geological Survey, Mineral Resources Database (website): http://tin.er.usgs.gov/geology/state/sgmc-unit.php?unit=CATv1%3B0

Stoffer, P. W., 2006, Where's the San Andreas Fault? A Guidebook to Tracing the Fault on Public Lands in the San Francisco Bay Region.U.S. Geological Survey General Information Product 16, 123 p. Available on-line at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/2006/16/.

Sylvester, A. G., and Crowell, J. C. 1989, The San Andreas Transform Belt, Field trip guidebook T309, 28th International Geological Congress, American Geophysical Union, Washington, D. C.

Taliaferro, N.L., 1948, Geologic map of the Hollister quadrangle, California: California Division of Mines and Geology, vol. 143, 2 plates. |

|