San Andreas Fault Walk in San Juan Bautista

|

|

| Field trip overview: San Juan Bautista is one of the oldest towns on the Central Coast of California. At the entrance to the town is a sign that calls itself "the City of History"—for good reason. This fieldtrip report is a guide to the town's natural and cultural history (two topics that cannot be justifiably separated!). Geologically, the region around and including "San Juan" is spectacular. The historic downtown area is built on a rising crustal block on the west (Pacific) side of the San Andreas Fault. The region surrounding San Juan Bautista is host to rocks of all types (igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic). These rocks range in age from recently formed (spring-fed travertine deposits) to rocks that date back at least 200 million years (seafloor rocks formed in Jurassic Period) Some rocks exposed in the Gavilan Range may be over a billion years (pieces of ancient continental crust ripped from far away places and carried to their curren location by ongoing plate tectonic forces. |

Click on maps and photos for larger views. |

|

|

| Central Coast regional map showing San Juan Bautista |

San Juan Bautista local field trip destinations map |

Geography

The town is located along the south side of San Juan Valley (drained by the San Benito River). To the south is the Gavilan Range with it's nearby high peak: Fremont Peak (named after US western explorer John C. Fremont) but was originally named Gavilan Peak (gavilan means hawk in Spanish). Tthe Lomita Muertas ("the barren hills" in Spanish, also named the Flint Hills) rise on the north side of San Juan Valley beyond the San Benito River. To the northwest is the Santa Cruz Mountains with its highest peak, Loma Prieta, in the distance. At the west end of the valley is the confluence of the San Benito River with the Pajaro River. West of the confluence the Pajaro River flows through a canyon (Pajaro Gap) on its route through Watsonville before draining into Monterey Bay. Visible to the west beyond Hollister is the Quien Sabe Range (Spanish for "who knows? range") which are part of the more extensive Gavilan Range.

|

|

|

| San Andreas Fault Walk map of San Juan Bautista State Historic Park and Old Mission area |

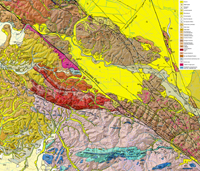

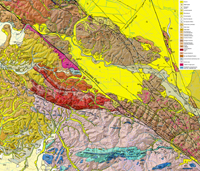

Geologic Map of the San Juan Bautista region (modified from California Geological Survey, Monterey 1:100,000 scale map, 20022) |

| Between the north end of the Gavilan Range and the south end of the Santa Cruz Mountains is a relatively low, erosionally dissected plateau. This gap allows fog to roll through between to mountain ranges into the San Juan Valley region. It also was the route used by the first Spanish expedition (families and soldiers totallying about 200 people) lead by Juan Bautista de Anza. The group travelled overland from northern Mexico, passing over the low plateau between Salinas Valley into San Juan Valley in 1769 before continuing north to settle in the region around San Francisco Bay. What they saw as they passed through San Juan Valley was probably marshlands, an abundance of wildlife, and scattered Indian villages (Amah Mutsun Ohlone tribe) and associated croplands along the San Benito River—a landscape and community that probably appeared much the same for the previous few thousand years. |

Short History of San Juan Bautista

Mission San Juan Bautista was established on June 24, 1797, the location was selected by Fr. Fermin de Lasuen, Presidente of the California Missions. Mission San Juan Bautista was the 15th of 21 missions established in California. The mission was established roughly midway between missions in Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo (in Carmel, CA) and Mission Santa Clara (near southern San Francisco Bay). The road connecting the 21 missions was named the El Camino Real ("The Kings Highway") and later renamed in sections—the Monterey Highway.

The Old Mission is located on a low hill overlooking the fertile San Juan Valley, near the intersection of the San Benito and Pajaro Rivers. Prior to Spanish conquest, the land belonged to the Mutson Indians, a subset of the Ohlone Indians the lived in the region from San Jose to Monterey. At the time the Spanish first arrived in the area probably more than 3,000 indians lived in small villages along the San Benito and Pajaro Rivers. These indians were subjugated into working for the missions, and many more were brought in from elsewhere. Like elsewhere in the world at the time, the mission's indians suffered greatly under subjugation—diseases, harsh treatment, loss of family, idenity and freedom, and associated depression.

Construction of the first mission church began in 1797, but it was heavily damaged by a large earthquake in 1798. Construction resumed, but again construction efforts were severely damaged by another major earthquakes (actually 4 large ones in one day, and likely many smaller ones in the following weeks) in 1803. It was after that earthquake that plans were made to build the next version with enough reinforcement to survive a major earthquake while occupied by a thousand people. The cornerstone of the new (now Old Mission) is dated 1803.

Living conditions for the indians was extremely poor, and most died of disease and related depression illnesses not long after arriving at the mission. By 1812 only little over a thousand indians remained working for the mission. In 1835 the California missions were secularized in 1835, and most of the mission property was seized by the Mexican government. At that time, the mission lands were taken and the Indians were no longer under direct subjugation of the church, but conditions for them got no better. All their land had been taken and they were still mostly treated harshly by the new land owners (pointedly, not by all) or abandoned to starve, or flee, or to assimilate into Hispanic communities, hiding their native identities. In the time between 1797 when the mission was established to when secularization took place, as many as 19,000 indians were forced to move to San Juan to work for the mission1. Their remains are buried in the fields around San Juan with a few thousand buried in the historic graveyard behind the mission (in an area adjacent to the San Andreas Fault scarp).

However, Mission San Juan Bautista was still used for Catholic religious services and remained the center of activity in the region. Land around the San Juan valley was split up into rancheros (land grants). The discovery of gold in 1848 brought a flood of non-spanish europeans and other immigrant groups into the area. The remaining indians were forced to work on ranches or crowded into a small adobe and stone housing area near the mission.

San Juan continued to experience earthquakes with large ones reported in 1836 and 1838, but little damage was reported.

With the Gold Rush, the area population grew rapidly and San Juan began to experience it's "Hay Day" - litterally! Hay and other crops were harvested in the San Juan valley and shipped by wagon northward to growing communities in San Francisco. San Juan was a major crossroads along the route between Los Angeles and San Francisco, between the mercury mines in New Idria, and roads to Watsonville and Santa Cruz. San Juan Bautista has the only original Spanish Plaza remaining in California. The Plaza and the main street (3d Street, The Alameda) was a thriving commerce district with hotels, stores, businesses, restaurants, barracks for soldiers, and an abundance of bars and bordellos. The town was a destination for entertainment of all kinds. When fairs and rodeos took place, the town's population would swell to about 20,000 residents. The El Camino Real route became the Old Stage Road (now the Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail). In the late 19th century it was nearly a one-day stage ride from the Salinas Valley over the Stage Road into San Juan, then another full day ride northward to the Bay Area.

1867—the start of a bad year for San Juan.

The year 1868 experienced the original Great San Francisco Earthquake (a major quake on the Hayward Fault, not the San Andreas Fault). It caused severe damage in the very rural side of the East San Francisco Bay area, but damaging shaking was experience throughout the region, including in San Juan where damage was relatively minor. However, other problems were taking place that were more human in nature. It was also the year that the dominantly non-Hispanic and Indian town of Hollister was established (San Juan was by then a community still dominated by other nationalities: Hispanic, Oriental, and Indian. A choice was made to bring a rail line linking Hollister to San Francisco, by passing San Juan, and essentially stealing the majority of commerce. In that year San Juan also experienced a major fire that burned down a large section of downtown and a surrounding neighborhood. Perhaps most tragic was that the remaining indians, living in closely packed housing were wiped out by a smallpox outbreak. San Juan's asperations to become the economically covetted county seat ended with the split of San Benito County away from Monterey County (Hollister got the county seat for San Benito, and Salinas got Monterey County).

Despite all the troubles, San Juan Bautista incorporated as a city in 1869. As a result of the fire, San Juan establish a fire station, the first in California. San Juan continued to struggle on through difficult economic times whereas other cities connected to rail lines in the region prospered and grew rapidly by comparison. In 1895, the present mission buildings and 55 acres were given back to the Church by Federal decree of the United States government. Just south of downtown a cement plant with lime kilns was established in 1903 and named the Old Mission Portland Cement Company. The cement plant utilizing marble mined in the foothills around Fremont Peak and remained a major employer in town until it finally closed into the 1970s.

The mission was heavily damaged in the 1906 earthquake, but the town site on the west of the San Andreas Fault survived relatively unscathed compared to homes and buildings built on the unconsolidated sediments that underly the fields north and east of the Mission where earthquake shaking was amplified. Ground rupture was noted in some places along the trace of the fault in the San Juan area.

San Juan experienced some growth with the appearance of automobile transportation. Before completion of Highway 101 all the traffic between SoCal and the San Francisco Bay region

went through downtown San Juan. South of town, the Old Stage Road was partly replaced by a new route through the foothills of the Gavilan Range named the Salinas Road (or San Juan Grade). In town, the main travel route from Salinas connected to The Alameda (3rd Street in downtown San Juan) and continued northward out of town on the San Juan Highway to Gilroy and beyond. In its day, downtown San Juan was bustling with vehicular traffic, including large trucks. Construction of Highway 156 between the Coast Highway and Hollister (and beyond) bypassed San Juan, and essentially killed the town as a thriving business community. Today the town is preserved as the Downtown Historic District and San Juan Bautista State Historic Park next to the Old Mission. The community is now largely a commuter and retirement community, and a regional destination for weekend travelers and tourism, but nothing like in it Hay Days when huge events, such as the San Juan Rodeo, took place in town. San Juan's population dipped to a census low of 1,359 but has steadily risen to its 2011 census population estimate of 1,890.

|

San Andreas Fault Walking Tour

|

Click on images for a larger view. |

Guided walking tours are organized by Tops Rock Shop and GeoZeum at 209 3rd Street. The field trip groups gather across the street from the Rock Shop at the gates to San Juan Bautista State Historic Park (introduction and walk overview discussion).

Stop 1: Corner of 3rd Street and Mariposa Street. Introduction and overview of field trip for participants.

Question: What do geologists look for when searching for faults in a place like San Juan? Answer: offset, cracked, and bent walls, and stories from long-lived local residents. Note: nearly all rocks you see in walls and along paths in town were probably hand carried by indians from stone quarried in the foothills outside of town. The rocks were recycled over and over from walls of older structures. Note: The town's only bank is located on the site of an earlier adobe building built in 1849 that later burned in 1867. The 1867 fire demolished a large part of town south and west. After the fire, the town residents established a firehouse—the first in California! |

|

| View looking downhill (south) along Mariposa Street to fire-scorched hills (burned in 2012) with fog flowing over the Gavilan Range. |

Stop 2: Two-Story Outhouse—a rare addition, connected to the Plaza Hotel. Women got the second floor.

The Plaza Hotel was originally a one-story adobe barracks built in 1813-14 for soldiers stationed in San Juan by the Spanish government. In 1858 Angelo Zanetta added a second story to the building and operated it as a hotel for many years. Note: Cracks appeared in the stucko-covered adobe walls on the west-facing outer wall of the Plaza Hotel after a small earthquake in November, 2011. Note: A trench dug near the Old Mission in 2010 revealed that sediments (mostly gravel) underlying the area were deposited on an alluvial fan until about 20,000 years ago. The fan formed around the mouth of San Juan Canyon and drained toward the San Benito River. However, uplift along the San Andreas Fault uplifted the hill where the Mission and Plaza are located. What was "downhill" 20,000 years ago is now "uphill" on Mariposa Street! |

|

| Park wall with cactus, and two-story outhouse attached to the Plaza Hotel on Mariposa Street. |

| Stop 3: Settlers' Cabin (with gardens)—located in forested lot on the corner of Mariposa and 2nd Street, opposite from the Plaza Hotel and the Old Mission. The Settlers' Cabin was originally located in the fields east of town near Mission Vineyard Road. It was probably originally constructed in the 1830s. Note: many of the rocks around the garden are typical of the bedrock in the hills around San Juan. Look for marine fossils in some of the chunks of brown sandstone. Other rocks include specimens of granite, gneiss, metachert, and marble. |

|

| Settlers' Cabin |

| Stop 4: Old Mission San Juan Bautista and Plaza: The layout of the Old Mission and Plaza area is typical of old Spanish community design. The Plaza is the last remaining plaza associated with missions in California. The Old Mission itself is the largest. after the first church and buildings were heavily damaged by earthquakes of October 1798 and 1803. The cornerstone of the mission was laid in 1803. By then the population of the settlement of San Juan Bautista was growing quickly with Spanish settlers moving in from Mexico and subjugation of the regional Indian tribes.The church was constructed by indian labor and dedicated in 1812. Based on experiences with earthquakes the church was designed a little stronger to prevent large causualties from earthquake damage (making it perhaps the oldest earthquake-engineered building in America). It survived large earthquakes in 1836, 1838, and 1868, but was heavily damaged in the 1906 earthquake with little damage from the 1989 thanks to earthquake retrofitting. |

|

| Old Mission San Juan Bautista and Plaza |

| |

Stop 5: View of Fremont Peak: A good place to see the mountain peak is just outside of the Old Mission Gift Store. Fremont Peak is the highest point in the northern Gavilan Range. Formerly named Gavilan Peak, the mountain became part of regional history when US Army explorer John C. Fremont and his crew climbed the peak in 1848 to make observations, but drew ire from local Mexican General Castro when it was reported he a ascended the peak and planted a US flag on Mexican soil. Fremont and Company fled the mountain before gunfire started. The mountain range is underlain by Salinian basement complex: granitic rocks and metamorphic rocks of Cretaceous and older age. Salinian rocks were once attached to southern California and carried northward by plate tectonic forces along California's coastal fault systems (on the west side of the San Andreas Fault). The high peak is composed of marble of undertermined ancient age.

Stop 6: Old Mission Church and Pioneer Cemetary: The Church at Mission San Juan Bautista is the widest of the California mission, having 3 isles and seating for about 1,000 people. The Church is ornately decorated inside. One of the interesting design facets is that on the morning of the winter solstace sunlight streaming into the front of the church strikes the alter—a dazzling display to experience the astronomical new year! Next to the Church is the Mission Cemetery. A sign next to the gated entrance states "buried in this sacred ground in unmarked graves ar about 4300 mission indians, Spanish and pioneer settlers." A wall along the Mision Cemetery basically follows the San Andreas Faultline. It shows evidence of repairs and additional layers added over the centuries. Afred Hitchcock filmed the 1956 movie, in part, in San Juan Bautista. For the movie his artists added a bell tower to the Old Mission, because an original tower was removed for potential earthquake failure. The current bell arrangement was added later.

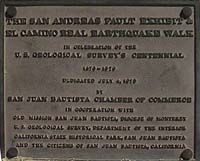

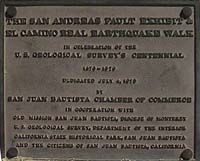

Stop 7: US Geological Survey comemmorative plaque for San Andreas Fault Walk: Located near a statue representing St. John the Baptist is a small monument with a brass plaque placed in this location in 1979 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the establishment of the U.S. Geological Survey. This location was chosen for good reason. Starting with the 1906 earthquake, the geoscience community began to study earthquakes and fault system. The San Andreas Fault is perhaps the most studied geologic feature on the planet. The fault's right-lateral strike-slip movement in the 1906 earthquake defied established theories about the origin of mountain ranges, and ultimate contributed to the establishment of modern Plate Tectonics Theory, with thegreater San Andreas Fault system (including faults throughout California and offshore) representing a complex boundary between the North American Plate and the Pacific Plate. The Pacific Plate is moving northward relative to the North American Plate at a rate of about 2 inches per year with most of the slip taking place along the San Andreas and Calaveras Faults (in San Benito County). Where the fault is locked up, pressure builds up until rupture takes place causing earthquakes. Fortunately, in the San Benito County region, the faults are mostly gradually creeping, preventing massive earthquakes from happening in the immediate vicinity. However, a few miles north of San Juan, the San Andreas Fault is not actively creeping, and other faults in the region have a history of causing damaging earthquakes. Predicting earthquakes has remained an impossibility, so disaster preparedness is the only practical means of preventing severe damage to property and injury.

Stop 9: Stairs descending San Andreas Fault escarpment: The stairway at the north side of the Plaza descends the San Andreas Fault scarp. The San Andreas Fault is moving laterally, with the side the mission is on is moving north and west relative to the side the valley side. However, the fault in this location also has movement in a vertical direction. Studies of the sediments under the mission grounds show that the surface where the Plaza and Old Mission is located was a gravel-rich alluvial fan that had spread across the landscape from the mouth of San Juan Canyon. As little as 20,000 years ago, the alluvial fan spilled across the fault zone, merging with the river floodplain and lakebed deposits. Today the hilltop is displaced upward about 70 feet above the surface of the fields. Fault zones are typically complex. A fault plain deep underground may by be a simple break, but closer to the surface faults will bifrucate and splay, creating breaks around rotating blocks of earth, and where steep slopes occur gravity with produce slumps that may mask or obscure fault traces. The USGS have mapped the trace of the fault along the edge of the field at the slope, however, historical reports from the 1906 earthquake described rupture break along the slope above the cement rodeo grandstand, about halfway up the staircase. Small cracks in a low wall along the staircase reveal the location of the break, however there is no significan horizonal displacement observable on the stairs, suggesting that the slip is taking place further down the slope below the El Camino

Real.Stop 10: El Camino Real, views of Lomerias Muertas, San Andreas Fault scarp. Support wall behind mission cemetary shows multiple layers of additions with possible repairs to damage caused by the 1906 earthquake. Note: Ancient Lake San Juan filled the valley until about 7,000 years ago (reason why the fields are so flat). At the time the mission was established wetland marshes covered much of San Juan Valley; ditches were dug to drain the fields. Note: tree line opposite the old rodeo field was the location of a rail line that connected the Cement Plant (south of town) to the Union Pacific rail line that follows the Pajaro River from Watsonville to Gilroy (and beyond).

Stop 11: Cemetery Wall along San Andreas Fault scarp:As time passed, the cemetery filled. Like old church cemeteries in Europe, the ground level rose as the cemetary filled. The old wall shows 4 levels of additions in its construction. Old adobe roof shingles and bricks can be seen included in the oldest layer of construction.

Stop 12:

View of Quien Sabe Range: At the east end of the El Camino Real walking path, the path climbs up the fault zone escarpment to become Franklin Street. A gap between trees allows a view to the east toward a gap between the Lomitas Muertas (on the left) and the Hollister Hills (on the right). Beyond the gap is Hollister Valley and the Quien Sabe Range in the distance. The Calaveras Fault runs through downtown Hollister and another major fault, the Quien Sabe Fault, runs along the base of the west facing mountain front. The high peaks in the Quien Sabe range are weathering-resistant igneous rocks preserved as vents and dikes assocated with an ancient volcanic field that formed about 13 to 9.5 million years ago. Like the Pinnacles Volcano to the south, the Quien Sabe volcanoes erupted along the newly forming San Andreas Fault system as it propogated northward across the region as the western plate boundary of the North America changed from a subduction zone to a transform boundary.

Stop 13: Broken stone wall near the Faultline Restaurant: The Faultline Restaurant is located at the top of the San Andreas escarpment although the rupture zone of the 1906 earthquake extended through the patio in the restaurant grounds. Small offsets are visible in an old cement driveway are a result of fault creep or associated slumping in the rupture zone. At the high point of the road is a brick wall that has a fracture where the break at the tow of the wall is about 2 inches wider than the base of the wall. The break could be a result of expanding tree roots but it's location at the hilltop suggests that it may be associated with cracking with the slowly rising anticline. Franklin Street was repaved in the summer of 2012. Before paving, the old asphalt roadway was heavily broken up in the vicinity of the ridge top and extending down the escarpment.

Stop 14: Coastal Redwood and location of historic Indian housing in park maintenance area: During construction of the mission, indians were forced to move to a densely populated housing area that existed in the area that is now the park maintenance area. Probably more than 1000 indians may have been packed into this small area. The densely packed housing no doubt contributed to why all the indians died from a smallpox outbreak in 1868. After the indians were gone, the stones used in the construction were used in wall construction elsewhere around town. Note: visitors from beyond the region may enjoy examining the relatively large coastal redwood along Franklin Street near the crest of the hill. An unobstructed view of Fremont Peak and the northern foothills of the Gavilan Range is visible near the entrance to the park maintenance area (which is unfortuantely closed to the public). Note: Franklin Street descends downhill to 4th Street to the low point where historically a branch of San Juan Creek used to flow around the rising hilltop in the mission area. North of the Park Maintenance area the escarpment ends where the anticline plunges beneath younger sediment cover in the vicinity of the town's sports playing field.

Stop 15: Old town jail and Park restrooms: Walking back toward the Plaza on 2nd Street, examine the rock walls along the beneath the Plaza Stables building—probably composed of rock removed from the indian settlement area. On the corner of 2nd and Washington Streets are the park restrooms and a small building used as the historic town jail. In it's hay days, San Juan Bautista was a racous place, hosting as many as 20 establishments serving alcoholic beverages and probably as many bordellos. It is possible to imagine on a weekend night hearing the shouts and gunshots of excited men riding into town from the surrounding ranches. The town has a history of numerous lynchings and other wild and bewildering acts that contribute to the colorful history of the town.

Stop 8: Plaza Hall, Plaza Stables, and Vicky Cottage: The stables building grounds on the opposite side of the Plaza are accessible for a $3 entrance fee (payable in the Park Office in the Castro/Breen House). Exhibits in the park building contain an abundance of historical artifacts which visitors can marvel at. From a geologic perspective there are some facets worth considering. The Plaza Hall was constructed in the 1850s, replacing an earlier building on the site. The Vicky Cottage used to be a Wells-Fargo office originally located on the corner of 3rd and Mariposa (where the town bank is located). The Vicky Cottage was moved to its current location in 1885. It can be assumed that at the time of construction and layout of the Plaza and Plaza Hall that the ground surface was leveled. However today, on the east side of the Plaza the ground is gently warped with the high point centered in the middle of Plaza Hall. The area is on the crest of an anticline that is actively rising on the west side of the San Andreas Fault. The Vicky House is situated directly on top of a fault trace that ruptured in the 1906 earthquake.

Stop 16: California Pepper Tree (Schinus molle): San Juan is host to many old California Pepper Trees. These attractive trees have a handsome, rustic look with weeping branches which yield clusters of pinkish fruit in fall and winter. This tree is native to the Andes Mountains of Peru and belongs to the cashew family. Seeds were collected by Spanish colonials for tree planting into North America.

Stop 17: Historic adobe building (fromerly an famous art galery - Galeria Tonantzin) located on the southeast corner of 3rd and Washington Streets (right next to Jardines Mexican Restaurant and Garden Patio). The historic adobe building has a hatch in its floor that leads to one of possibly several historic tunnels connecting to the mission and served of questionable purpose. All the tunnels are now inaccessible.Other old adobe buildings on 3rd Street (The Alameda) date from the Spanish era before secularization of the Old Mission.

|

|

| Fremont Peak visible over the top of the Castro/Breen House (former soldier barracks). |

|

| Old Mission Church at at San Juan Bautista |

|

| Commerative USGS plaque |

|

| San Andreas Fault scarp and El Camino Real path |

|

| Cemetary wall behind Old Mission |

|

| Lomerias Muertas north of San Juan Valley |

|

| Quien Sabe Range east of Hollister Valley |

|

| Broken wall by Faultline Restaurant on Franklin Street |

|

| Coast redwood on Franklin Steet-looking south downhill. |

|

| Plaza Hall and Plaza Stables |

|

| Vicky Cottage is situated on a fault trace |

|

| California Pepper Tree |

|

Galeria Tonantzin art gallery

|

Places to visit to learn more local history and geology:

Stop A: Tops Rock Shop & GeoZeum - this museum store has maps and exhibits about local geology. The rock shop offers area tours and introductory geology classes to groups visiting San Juan Bautista.

Stop B: Visitor Center, San Juan Bautista State Historic Park - a $3 fee is required to tour the historic buildings and exhibits throughout the park buildings. The visitor center also has a small book store and museum.

Stop C: Old Mission San Juan Bautista, Gift Shop Entrance to Mission - The Gift Shop provides access to the Church, Museum, and garden area associationed with the Mission. A donation fee is requested to visit the mission. |

|

| Tops Rock Shop and GeoZeum on 3rd Street |

| |

Selected references Selected reference sources: note that the information presented here was taken from numerous historic plaques and signs around town, and knowledge gained from numerous local resident "historians," many whom are descendants of early settlers in the area. Some of the links below may have changed.

1Val Lopez, director, Alma Mutsun Tribe, personal communication, 2012

2Wagner, D.L., Green, H.G., Saucedo, G.J., and Pridmore, C.L., 2002, Geologic map of the Monterey 30'x60' Quadrangle and adjacent areas, California. California Geological Survey, Regional Geologic Map No. 1, 1:100000 scale: http://www.quake.ca.gov/gmaps/RGM/monterey/monterey.html

City of San Juan Bautista (official city website): http://www.san-juan-bautista.ca.us/index.htm

Gilroy Dispatch (newspaper), Amah-Mutsun: Recognition from City of San Juan Bautista is 'icing on the cake': posted Tuesday, June 19, 2012, URL.

Old Mission San Juan Bautista (mission website): http://www.oldmissionsjb.org/

Curry, R., 2003, Pájaro River Watershed Flood Protection Plan: Watershed Institute, CSU Monterey Bay, Seaside, California, 64 p.: http://www.pajarowatershed.org/archive/uploads/Flood%20Protection/Watershed%20Studies/Curry%20Flood%20Protection%20Plan%202003.pdf

Perazzo, P.B. and Perazzo, G.P., 2012, San Benito County List of Stone Quarries, Etc.:

http://quarriesandbeyond.org/states/ca/quarry_photo/ca-san_benito_photos.html

San Juan Bautista, community statistics: http://www.city-data.com/city/San-Juan-Bautista-California.html

Stoffer, P.S., 2006, Field-trip guide to the Hollister and San Juan Bautista area (Chapter 2): Where's the San Andreas Fault? U.S. Geological Survey, General Interest Publication no. 16, p. 19-32.http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/2006/16/

|

|