12.1

12.1

Coastlines are a dynamic interface between land and sea. Coastlines preserve evidence of many process from the past, going back hundreds, thousands, even millions of years. Coastlines are shaped by an ongoing series of processes involving daily wind and wave action, tides, occasional storms and superstorms, earthquakes, and massive tsunamis. Coastlines reflect process of their origin including erosion of bedrock features, and are influenced by regional geology, geography, and climate.

Understanding coastline dynamics is important considering that about 75% of the worlds megacities are on coastlines. According to the United Nations. presently about 40% of the world’s population lives within 100 kilometers of the coast, with hundreds of millions living in low-lying coastal areas (below about 10 meters elevation).

Wave erosion is persistent and intense, especially when storm waves combine with high tides. As a result, coastal landforms are generally delicate, and short-lived features.

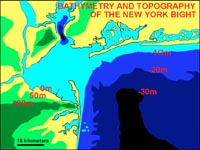

The sediment supply to coasts are offset by erosion rates along shorelines. Sediment supply is influenced by climate factors and geography, and can vary significantly from place to place, season to season, and by isolated events, such as changes caused by a massive superstorm (Figure 12-2).

|

Click on thumbnail images for a larger view. |

Fig. 12-1. New York, the largest coastal city in North America. More than 12 million people in the US live in regions within 3 meters above current sea level.

|

12.2

Classifications of Coastlines and Shoreline Features

Three different classification schemes of coastlines include:

a. Primary or Secondary Coastlines

b. Active or Passive Margins

c. Emergent or Submergent Coasts

Note below that characteristics of each classification scheme overlap and complement each other. |

Fig. 12-2. Hurricane Katrina, North America's most expensive disaster, wiped out an estimated 328 square miles of coastal land along the Gulf of Mexico. Fig. 12-2. Hurricane Katrina, North America's most expensive disaster, wiped out an estimated 328 square miles of coastal land along the Gulf of Mexico. |

12.3

Primary and Secondary Coastlines

Primary: Young coasts formed by terrestrial influences, not significantly altered by marine processes.

Secondary: Coasts that have been significantly changed by marine processes after sea level has stabilized.

|

Fig. 12-3. Jade Beach, CA

|

12.4

Primary Coasts - 5 Types

Ria Coasts: Drowned river valleys caused by a rise in sea level.

Examples: Chesapeake Bay (Figure 12-4).

Glacial Coasts: Coastlines influenced by recent glacial activity such as glacial cut “U shaped” valleys called “fjords.” Examples: Norway, British Columbia, Alaska, Hudson Valley, New England region, Long Island (Figure 12-5).

Deltaic Coasts: Coastlines associated with active river and delta systems.

Examples: Mississippi and Nile Rivers (Figure 12-6).

Volcanic Coasts: Coastlines associated with recent or active volcanoes (mostly basaltic or andesitic volcanoes).

Examples: Hawaii, Aleutian Islands, Japan, Philippines, Indonesia (Figure 12-7).

Fault/tectonic Coasts: Coastlines associated with major active fault systems along continental margins

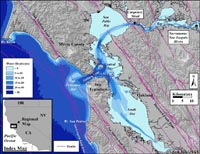

Example: San Andreas fault going off shore at San Francisco (Figure 12-8). |

Fig. 12-4. Ria Coast: Chesapeake and Delaware Bays (estuaries), and the Delmarva Peninsula. Sea-level rise has back filled river valleys draining into the Atlantic Ocean. Ridges on land became peninsulas.

|

Fig. 12-5. Glacial Coast: Kenai Fjords NP, Alaska

|

Fig. 12-6. Deltaic Coast: Nile River Delta

|

Fig. 12-7. Volcanic Coast: Hawaii Volcanoes NP

|

Fig. 12-8. Tectonic Coast:

Thornton SP, San Francisco

|

|

12.5

Secondary Coasts

Secondary coasts are coastlines that have been significantly changed by marine processes after sea level has stabilized allowing erosional and/or depositional processes to dominate shaping of the landscape. However, to explain this better, we need to examine the other classifications of coastlines first.

|

Both primary and secondary coasts are influenced by whether they are active or passive continental margins (the second method of coast classification).

Both primary and secondary coasts are influenced by whether they are emergent or submergent coastlines (the third method of coast classification - discussed below). Passive margins tend to be submergent due to the ongoing rise in sea level (Figure 12-10). In contrast, active margins can be both emergent or submergent depending on local tectonic forces, such as caused by faulting.

|

|

|

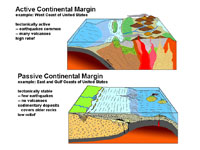

| Fig. 12-9. Active versus passive continental margins. |

Fig. 12-10. Changing sea level trends around North America. |

12.6

Coastlines on Active and. Passive Continental Margins

In North America, the Pacific Coast is an active continental margin, whereas the Atlantic Coast is a passive continental margin (Figures 12-11 and 12-12).

An active continental margin is a coastal region that is characterized by mountain-building activity including earthquakes, volcanic activity, and tectonic motion resulting from movement of tectonic plates. Active margins typically have a narrower and steeper continental shelf and slope. They can also be subsiding or uplifting. Active continental margins are also associated with subduction zones, often include a deep offshore trench. The Pacific Coast is an active margin that is characterized by narrow beach, steep cliffs, rugged coastlines with headlands and sea stacks (see features discussed below).

Passive continental margins occur where the transition between oceanic and continental crust which is not an active plate boundary. Passive margins are characterized by wide beaches, barrier islands, broad coastal plains. Offshore passive margins typically have a wider and flatter continental shelf and slope. They are usually subsiding. Examples of passive margins are the Atlantic and Gulf coastal regions which represent setting where thick accumulations of sedimentary materials have buried ancient rifted continental boundaries formed by the opening of the Atlantic Ocean basin.

|

Fig. 12-11. Passive margin: North Carolina's Outer Banks region showing coastal plain, rivers, tidal estuaries, lagoon, barrier islands, and shallow Atlantic continental shelf.

|

Fig. 12-12. Active margin: San Francisco Bay and Monterey Bay region has actively rising coastal range mountains and sinking coastal basins.

|

12.7

Erosional coastal landforms or features

Emergent coastlines typically have sea cliffs carved by wave and current action along the shoreline, typically on secondary coastlines. The geometry of a coastline is largely a reflection of how some rocks along a coastline are more resistant to erosion.

Sea Cliffs, Wave-Cut Platforms and Features

* Sea cliffs form where persistent wave erosion carves into elevated coastlines.

* Waves erode the base of cliff, causing it to subside or fail (Figure 12-13).

* Waves carve a flat surface where they scour the seabed leading up to the beach creating a wave-cut platform.

* When sea level locally falls falls (such as from uplift of a regional earthquake) wave action scours out a new wave-cut platform, leaving remnants of the old seabed surfaces exposed as expose wave-cut bench (Figure 12-14). A wave-cut bench is a flat bench-like platform of rock typically preserved in the upper surf zone associated with an actively eroding sea cliff on an emergent coastline (Figures 12-14 and 12-17, also see marine terraces below).

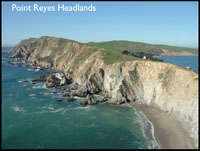

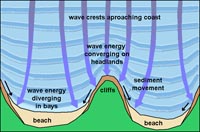

Headlands are rocky shorelines that have resisted wave erosion more than surrounding areas, forming points or small peninsulas that jut seaward. Small sandy beaches typically occur in bays between headlands (Figure 12-15).

Sea stacks are large rocky outcrops that have resisted wave erosion and stand offshore as the beach and sea cliff continues to erode landward

* Mound of rock and debris that eventually is taken to sea by waves.

* The product of a sea arch caving in

(Figure 12-16).

A sea cave is an underground passage or enclosed overhang carved into a sea cliff carved by focused wave action (Figure 12-17).

A sea arch is a natural rock arch caved by wave action. Sea arches form where two caves join together or where a cave cuts through a narrow fin of rock

(Figure 12-18).

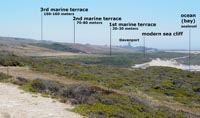

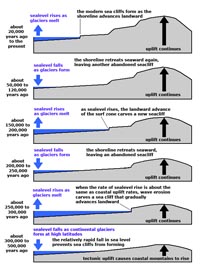

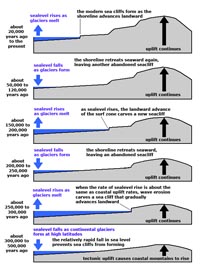

Marine terraces are elevated step-like benches formed by the combined effects of long-term wave erosion during the rise and fall of sea level on an emergent coastline (Figures 12-19 to 11-22). Marine terraces are old wave-cut platforms and benches that have been elevated by the land rising relative to the ocean surface. |

Fig. 12-13. Sea cliff rise above the wave-cut platform (with beach) at Del Mar Dog Beach, CA

|

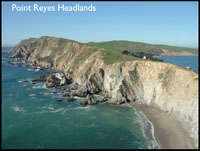

Fig. 12-14. Wave-cut platform, wave-cut bench, and sea cliffs on Point Reyes National Seashore, CA

|

Fig. 12-15. Headlands and bays at Point Reyes National Seashore. Fig. 12-15. Headlands and bays at Point Reyes National Seashore.

|

Fig. 12-16. Sea stacks along the coast at Olympic National Park, WA

|

Fig. 12-17. A sea cave and wave-cut benches at Wilder Ranch State Park, Santa Cruz, CA.

|

Fig. 12-18. A sea arch at Natural Bridges State Park, Santa Cruz, CA.

|

12.8

Elevated marine terraces

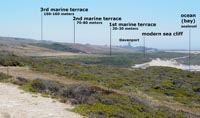

Elevated marine terraces occur in many locations along the California coastline, see Figures 12-19 and 12-20.

California preserves much evidence of geologic, geographic, and climatic changes caused by ice ages. During the last ice age, alpine glaciers and ice caps covered upland regions in the Sierra Nevada Range and Cascades volcanoes, but lower elevations were ice free (Figure 12-21). The formation of continental glaciers in North America and Europe caused sea level to fall almost 400 feet, causing the shoreline to migrate seaward as much as 10 to 70 miles (16 to 110 km) westward of the current coastline in some locations. This rise and fall of sea level happened with each glaciation cycle (of which there were many through the ice ages of the Pleistocene Epoch). In places where the California coastline is slowly rising, each of the major glaciation cycles is preserved as a step-like bench, called a marine terrace. The formation of marine terraces is illustrated in Figure 12-22. |

Fig. 12-19. Marine terraces at Davenport, California

|

Fig. 12-21. California at the peak of the last ice age. Glaciers covered the higher mountains, lakes filled inland valleys, and a coastal plain was extended offshore.

|

Fig. 12-22. Formation of marine terraces. This example shows the formation of two terraces. At least seven major terrace levels are preserved in some areas along the California coast.

|

Fig. 12-20. Step-like marine terraces on San Clement Island located offshore in southern California

|

12.9

Depositional coastal landforms or features:

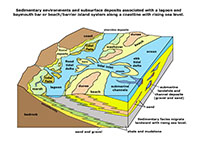

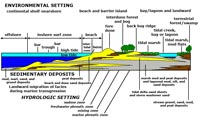

A beach is the most obvious depositional landform along a coastline. Beaches may change, grow, shrink, or even disappear with changing seasons, tides, and storm cycles. They migrate landward or seaward as sea level is either gradually rising of falling (Figure 12-23). Beaches are typically sandy, but may also consist of gravel or shell material. Features associated with beaches include beach berms and dunes in the upper beach region. Beaches along lagoons and the entrances to rivers may be sand bars or may be muddy and be associated with tidal flats. Areas overgrown with plants in the intertidal zone are called a marsh.

Spits are ridges of sand projected from land into the bay

(Figure 12-24). Over time they may change grow down current for many miles, but are often cut by tidal inlets.

A bay-mouth bar is a sandbar that stretches across a bay, separating it from the ocean (Figure 12-25).

Barrier islands are ridges of sand islands that run parallel to the coast (Figure 12-26). Spits may be split into barrier islands. In locations where inlets occur cutting across bay-mouth bars or barrier islands, tidal deltas can accumulate sediments on both ends of an inlet. Ebb tidal deltas form as the outgoing tidal current erode and move and deposit sand on the seaward side of an inlet. Flood-tide deltas form where incoming tidal currents carry sediments eroded from the ocean-beach side of a barrier-island inlet and deposit them in the lagoon or bay side of an inlet. |

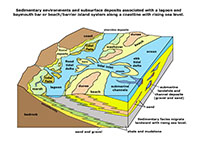

Fig. 12-23. Different kinds of coastal depositional environments illustrated and how they move with sea-level rise over time. |

Fig. 12-24. Spits: Rockaway Spit (right, on Long Island, NY) and Sandy Hook Spit (New Jersey projects northward into outer New York Harbor and Raritan Bay). |

Fig. 12-25. Bay-mouth bar: Bolinas lagoon has a baymouth bar. The bar is composed of sand eroded and transported along shore from the Point Reyes Peninsula (in the distance).

|

Fig. 12-26. Nauset-Monomoy barrier islands along Cape Cod's south shore, Massachusetts, with tidal deltas visible in the shallow waters on the landward side of the inlets.

|

12.10

Emergent and Submergent Coasts

Another important factor in understanding shorelines is tectonic activity and the rise and fall of sea level.

Submergent coastlines display characteristics caused when sea level rises or the land sinks down. Submergent coastlines:

* Contain estuaries and barrier bars, and barrier island systems.

* Ridges that separate valleys that propel into the sea.

Example: East Coast (see Figure 12-4).

Emergent coastlines display characteristics caused when sea level drops or the land rises (from tectonic uplift).

* Wave cut platforms and elevated marine terraces.

Example: West Coast California (Figure 12-27). This view is a view looking south along Torrey Pines Beach.

In some regions around the world, tectonic forces are pushing rocks up along coastal regions, mostly in regions associated with active continental margins. There areas are called emergent coasts and display features including sea cliffs and marine terraces (see below). Where sea level is rising faster than land is rising, or where coastal areas are sinking, it is called a submergent coast. Submergent coasts are associated with passive continental margins with wide coastal plains and continental shelves. Estuaries are associated with submergent coastlines formed when sea level rises and floods existing river valleys. Active margins can have both emergent and submergent coastlines in close proximity to each other. |

Fig. 12-27. San Diego's coastline displays characteristics of both emergent and submergent coastlines, having both seacliffs, headlands and marine terraces (emergent), and bays and estuaries filling flooded river valleys (submergent). View south along the Coast Highway at Torrey Pines Nature Preserve with La Jolla highlands in the distance..

|

12.11

Common Shoreline Features of Beaches and Barrier Islands

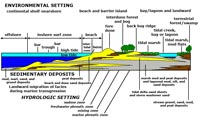

Figure 12-28 illustrates common shoreline features and shoreline depositional environments associated with beaches, barrier islands, and lagoons.

A beach is an accumulation of mostly sand (and some gravel) along a shoreline where wave action winnows away finer sediment. Beaches occur in the intertidal zone (the zone between highest and lowest tides). Above the high tide line the upper supratidal part of the beach is mostly impacted storm surges and by wind (forming dunes) (Figure 12-29).

A barrier island is a long and typically narrow island, running parallel to the mainland, composed of sandy sediments, built up by the action of waves and currents (Figure 12-30). Barrier islands serve to protect the mainland coast from erosion by surf and tidal surges. Examples include the Outer Banks in North Carolina and Padre Island in Texas. Barrier islands are most common on submergent coastlines associated with low-relief regions such as is present along the Atlantic Coast and Gulf Coast of the eastern United States. They form where the sea floor remains shallow for a long distance offshore.

An estuary is the mouth of a river or stream where the tide-driven flow allows the mixing of freshwater and ocean saltwater (Figure 12-31). A lagoon is a saltwater-filled bay or estuary located between a barrier island and the mainland.

A tidal flat is a nearly flat coastal area (at or near sea level) that is alternately covered and exposed by the tides, and consisting of unconsolidated sediments. |

Fig. 12-28. Coastal environments extend from offshore to inland estuaries and bays.

|

Fig. 12-29. Beach and coastal dunes at Point Reyes National Seashore, California

|

Fig. 12-30. Fire Island, NY, is a barrier island on the south shore of Long Island, NY.

|

Fig. 12-31. Tidal marshes and tidal flats along an estuary, Elkhorn Slough, CA.

|

12.12

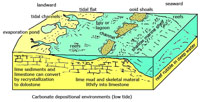

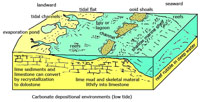

Coral Reefs, Keys, and Atolls

Biogenous carbonate sediments can accumulate faster than sea level is rising. Skeletal reefs (including coral reefs) thrive in the surf zone, and are able to weather wave action, although they can be heavily damaged by superstorm wave energy. The sediments generated by wave erosion and bioerosion (critters eating critters) contribute to the buildup of carbonate islands (keys) and atolls associated with fringing reefs forming around extinct and eroding volcanic islands (Figures 12-32 to 11-34). Keys and reefs of the world experience exposure and erosion during low sea levels during the ice ages. |

Fig. 12-32. Landforms associated with carbonate depositional environments.

|

Fig. 12-33. Coral reefs and keys, Kwajalein Atoll, Marshall Islands, South Pacific Ocean

|

Fig. 12-34. Mataiva Atoll, Tuamotu Archipelago, South Pacific Ocean

|

12.13

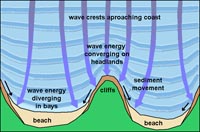

Shoreline Erosion

Shoreline erosion depends on several factors:

1) Amount of sediment to buffer land: If the sand supplied to a beach is less than the amount removed by shoreline erosion processes, the beach will retreat landward.

2) Amount of tectonic activity: Uplift along the coastline allows erosion to provide sediments to a coastline. If the coast is not rising, then shoreline will retreat landward.

3) Topography: Coastal uplands provide more sediments to beaches than flat coastal plain regions.

4)

Composition of land: Hard bedrock (such as granite) is harder to erode than softer unconsolidated deposits.

5) Waves and weather: The greater the waves and storm-generated currents, the more material can be eroded.

6) Coastline configuration:

Coasts facing prevailing storm waves are eroded faster than isolated bays and down-wind protected shorelines (Figure 12-35). |

Fig. 12-35. Wave refraction focuses wave energy on headlands and deposits sand in quieter bay settings.

|

12.14

Seasonal Erosional Changes to a Beach Profile

During the winter, storm-wave energy is most intense. Waves wash up on the beach and erode sand, and transport it offshore to where wave-driven currents aren't so strong and the sand accumulates on offshore bars. Heavier materials (gravel and boulders) are concentrated on the beach (Figure 12-36).

During the summer, lower wave energy prevails, and the sand gradually migrates back onshore, gradually expanding the beach seaward (Figure 12-37). |

Fig. 12-36. Cove Beach at Año Nuevo State Park (CA) in winter.

|

Fig. 12-37. Cove Beach at Año Nuevo State Park (CA) in summer.

|

12.15

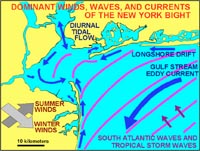

Longshore Currents and Longshore Drift

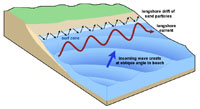

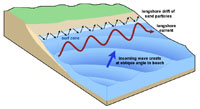

A longshore current is a current that flows parallel to the shore within the zone of breaking waves. Longshore currents develop when waves approach a beach at an angle (Figure 12-38). Longshore currents cause sediment transport called longshore drift. Longshore drift is the movement of sediments along a coast by waves that approach at an angle to the shore but then the swash recedes directly away from it. The water in a longshore current flows up onto the beach, and then back into the ocean in a “sheet-like” formation. As this sheet of water moves on and off the beach, it can transport beach sediment back out to sea. Objects floating in the longshore current move in a zigzag pattern up and down the beach as it moves down current. |

Fig. 12-38. Longshore currents and longshore drift are caused by waves approaching the beach at an oblique angle.

|

12.16

Rip Currents and Rip Tides

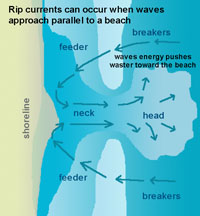

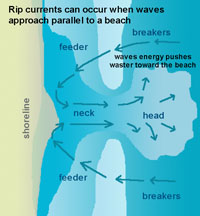

A rip current (or just “rip”) is a current that flows away from the coast (Figures 12-39 and 12-40). Rip currents form when wave break strongly in one direction, but weakly in another. In the surf zone, breaking waves produce currents that flow both along the shore and out to sea. Rip currents typical form on beaches with a sand bar and channel system in the nearshore area. A rip current forms as a narrow fast-moving current of water moving in an offshore direction. Obstructions in the water can also deflect current offshore. Rip current vary in size and speed (up to 6 miles per hour [10 km/hr], or faster than an Olympic swimmer). Rip currents move offshore and dissipate beyond the breaker zone. If caught in a rip current, swim parallel to shore to leave the current before heading for shore.

A rip current is different than a rip tide, which is current associated with the swift movement of tidal water through inlets and the mouths of estuaries, embayments, and harbors caused by the rise and fall of tides. |

Fig. 12-39. Rip currents are wave-generated currents that move in an offshore direction.

|

Fig. 12-40. Rip current can vary with size and intensity depending of waves and shore geometry.

|

12.17

12.18

Coastal Littoral Cells

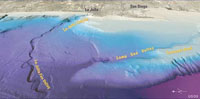

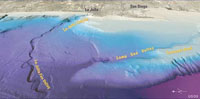

A coastal cell is a relatively self-contained compartment within which sediments circulate. A coastal cell contains a complete cycle of sedimentation including sources, transport paths, and sinks. In the San Diego area,

the Oceanside Coastal Cell extends from Dana Point to La Jolla Canyon; some of the sand is lost to Carlsbad Canyon as well (Figure 12-44). Streams and cliff erosion provide sediments to the shore zone. The arrow on the map indicates the predominant longshore current direction (and the direction of the migration of beach sand along the coast). Most of the sand moves down the coast and eventually drains down La Jolla Canyon and is deposited as turbidity flow deposits on the La Jolla Canyon deep-sea fan in the San Diego Trough (Figure 12-45). |

Fig. 12-44. Map of the Oceanside littoral cell and Carlsbad and La Jolla Canyons offshore.

|

Fig. 12-45. Sediments move from shore down La Jolla Canyon to the San Diego Trough at the southern end of the Oceanside littoral cell. |

12.19

San Diego's Coastal Erosion Problems Related To the Oceanside Coast Cell

The

dominant swell direction in northern San Diego County is from the northwest. This creates longshore currents that move sediments (longshore drift) from north to south along area beaches. The sand on northern San Diego County beaches are mostly derived from sediments derived from coastal erosion in the shallow nearshore, beach, and sea cliffs along the coast between Dana Point and Oceanside (much of it from along the undeveloped coast within Camp Pendleton north of Oceanside). In addition, large quantities of sandy sediments are contributed to beaches from streams (small rivers) that, during episodic floods, dump large amounts of fresh sediment into the nearshore environment, contributing about half of the sand supply to area beaches over time. The amount of sand from river sources is highly variable with the seasonal weather, year to year.

Large waves (swell) especially during high tides in stormy conditions can erode, transport, and deposit large quantities of sediments.

|

12.20

Shoreline Erosion Problems

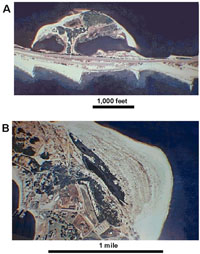

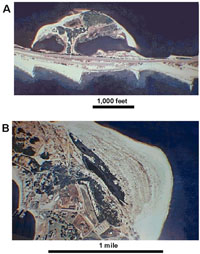

Shoreline changes quickly with natural forces; they are not a stable landforms. Coastlines, especially on the East Coast and Gulf regions, are constantly changing, especially from the impacts of superstorms. These coastal regions are underlain by unconsolidated sediments

that are easily eroded by strong currents. They remain relatively stable, as long as there is a new supply of sediment to replace materials eroded by longshore currents, tides, and storm waves. Figure 12-46 illustrates how much shorelines can change. In less than two centuries, Fire Island's eastern spit has grown about 5 miles (8 km) longer. The sediments creating this new land came at the expense of coastal lands father east on Fire Island, making the island increasing narrower. Barrier Islands are prone to be breached by storm erosion, creating new inlets, and filling in others.

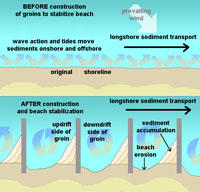

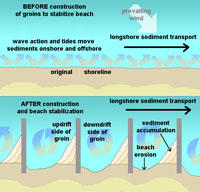

Many attempts have been made, often at great expense, to try to prevent the effects of erosion and deposition along coastlines. Common construction efforts include jetties, groins, and seawalls to protect harbors, infrastructure, and communities.

|

Fig. 12-46. Fire Island (on Long Island, NY) has steadily grown about 5 miles (8 km) longer since 1825 by longshore drift (also see Figure 12-41). Fire Island Inlet at the west end of Fire Island is scoured by rip tides, adding sediments to the tidal delta in Great South Bay.

|

12.21

Jetties and Groins

Jetties are built at entrances to rivers and harbors. Their purpose is to protect properties from storm and wave damage, and to keep sand out of channels (so that there is no beach). Jetties require high maintenance costs to manage because they impede longshore drift (which is continues relentlessly). Most the costs are for dredging sand from one side, and moving it down current to replenish sand to community beaches. Loss of the sand supply makes down current areas susceptible to beach loss and coastal erosion (a major problem for Southern California's coastal communities, Figures 12-47 and 12-48).

|

Fig. 12-47. Dana Point Harbor and Jetty

(Orange County, CA)

|

Fig. 12-48. Oceanside Harbor and Jetty (Northern San Diego County, CA)

|

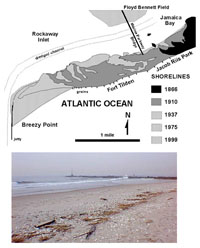

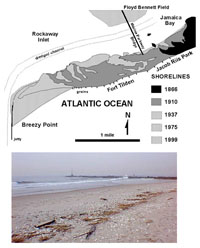

12.22

Groins are built as barriers perpendicular to the beach in an attempt to stabilize shorelines. Their purpose is to trap sand migrating along the shore by longshore drift (Figure 12-49). Figure 12-50A is an aerial view of a wash-over fan created by a breach in Sandy Hook Spit (on the New Jersey side of New York City's Outer Harbor (see Figure 12-24).The inlet formed when coastal storm waves and currents cut an inlet across the spit. Note the sand trapped on the left side of the groins (longshore drift is moving left to right). Figure 12-50B shows an accretionary prism of sand building up at the end of Sandy Hook Spit. Figure 12-51 shows the growth of Rockaway Spit on the north east side of New York's Outer Harbor. It has grown nearly 2 miles (3 km) since the end of the Civil War (1866). The area has been heavily modified by construction of groins and a jetty to keep the inlet to Jamaica Bay accessible to boat navigation. |

Fig. 12-49. Groins are designed to trap migrating sand by impeding the flow of longshore drift.

|

Fig. 12-50 (A&B). Groins, a washover fan, and accretionary prism on Sandy Hook, New Jersey.

|

Fig. 12-51. Map showing the growth of Rockaway Spit impacted by construction of groins and a jetty, and yes, disasters.

|

12.23

Other structures used to protect properties from the destruction by the sea

* Breakwaters are structures used to protect boats from large waves (jetties and groins are forms of breakwaters).

* Seawalls are walls built to protect land structures from large waves and coastal erosion (Figure 12-52 show an example of some seawalls used to stop cliff erosion).

* Rip Rap are piles of large boulders put on the beach or shoreline. They are cheap but take up beach space and are not as permanent as a seawall, and are unsightly and dangerous. However, they do create habitat for sea life that needs a hard substrate to live (Figure 12-53).

* Beach nourishment adds large amounts of sand to the beach to keep water away from land structures. Sand is dredged form harbor areas or mined from sand bars offshore and pumped onshore in slurries. The process is quite expensive.

|

Fig. 12-52. Seawalls built in Encinitas, CA are an attempt to stop sea cliff erosion.

|

Fig. 12-53. Rip-rap was used in the construction of the breakwater (Oceanside Harbor).

|

12.24

The Dam Problem

Dams have been constructed on most of the small rivers and streams throughout upland regions of San Diego County. The intentions of dam construction were to store water (reservoirs) and to reduce flood damage in low-lying communities. The problem is that dams have largely shut off the supply of sand from rivers and streams to the shore. One of the largest dams is for Lake Hodges on the San Dieguito River near Escondido, California (Figure 12-54). Construction of highway and railroad bridges, dikes, and causeways also restrict the flow of sediment-bearing water, preventing the migration of sediment to the coast. As a result, less sand is finding its way to the shore, resulting in narrower beaches. Without the protection of well-developed beaches, erosion of the sea cliffs are progressively endangering homes and infrastructure along the coast. |

Fig. 12-54. Lake Hodges Dam shut off sand supply.

|

Dam construction: The easy way to kill a coastal community.

Dams on rivers trap sediments that would otherwise find their way to ocean beaches. A classic example was the construction of a dam on Matilija Creek in Ventura County. The dam is currently being demolished in order to return the sediment flow to sensitive habitats along the river downstream, but also to return a sediment supply to the Ventura County coastline (Figure 12-54). Many other dams constructed in the 19th and 20th century are being removed for the same reasons. |

Fig. 12-55. The Ventura River (left) supplies massive amounts of sediments to the coast during infrequent floods, then persistent coastal erosion processes take over the action. Construction of the Matilija shut of much of the sediment supply to the coast. The dam is now being removed.

|

Coastal Dynamics—The Unending Saga

Sea-level rise due to global warming is a highly political topic of our times. The world's Scientific Community has been studying the changes happening around the world for many decades. Real-time observations show that the atmospheric temperatures are steadily rising along with the concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. What is perhaps most alarming is that the rate of sea-level rise is accelerating as the ice caps melt and the oceans expand from increased warmth (there are many NASA and NOAA websites on these matters). However, the threat doesn't seem to fit within the interest span of politicians and corporations keen on making high profits from the extraction of coal, oil, and gas. Sea-level rise will likely continue unabated until either we either consume all the economically available carbon-based resources, or human populations collaborate to change the fate we, collectively, are facing. |

12.25

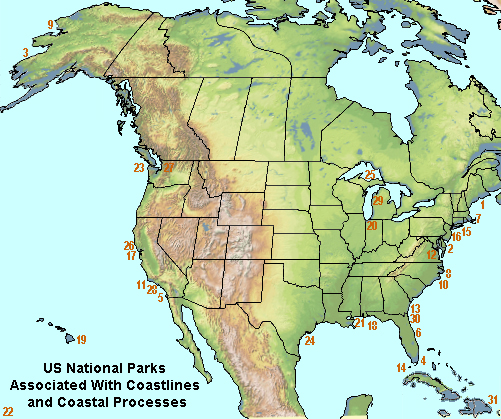

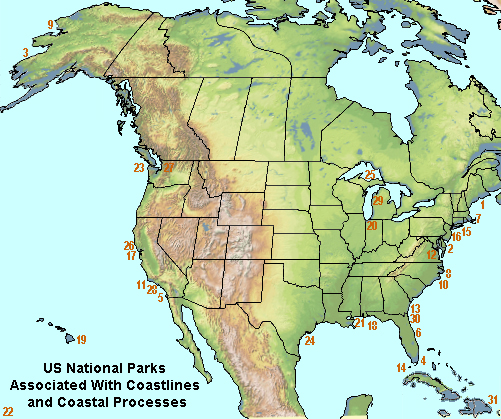

Selected National Parks Associated With Coastlines and Coastal Processes |

Acadia National Park, ME - 1

Apostle Islands National Lakeshore, WS - 32

Assateague Island National Seashore, MD, VA - 2

Bering Land Bridge National Preserve, AK - 3

Biscayne National Park, FL - 4

Cabrillo National Monument, CA - 5

Canaveral National Seashore, FL - 6

Cape Cod National Seashore, MA - 7

Cape Hatteras National Seashore, NC - 8

Cape Krusentern National Monument, AK - 9

Cape Lookout National Seashore, NC - 10

Channel Islands National Park, CA - 11

Chesapeake Bay, DC, DE, MD, PA, VA, WV - 12

Cumberland Island National Seashore, GA - 13

Dry Tortugas National Park, FL - 14

Everglades National Park, FL - 36

Fire Island National Seashore, NY - 15

Gateway National Recreation Area, NY, NJ - 16

Golden Gate National Recreation Area, CA - 17

Glacier Bay National Park, AK - 35

Gulf Island National Seashore, FL, MS - 18

Haleakala National Park, Hawaii -39

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, HI - 19

Indiana Dunes National Park, IN - 20

Kenai Fjords National Park, AK - 34

Mississippi Gulf National Heritage Area, MS - 21

National Park of American Samoa - 22

Olympic National Park, WA - 23

Padre Island National Seashore, TX - 24

Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, MI - 25

Point Reyes National Seashore, CA - 26

Redwoods National Park, CA - 37

San Juan Island National Historical Park, WA - 27

Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, CA - 28

Sitka National Historical Park, AK - 33

Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, MI - 29

Timucuan Ecological & Historical Preserve, FL - 30

Virgin Island National Park, VI - 31

Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument, VI - 31

Voyagers National Park, MN - 38

|

The coastline of United States has an abundance of national parks. The West Coast is an active plate margin with cliffs and mountain fronts extending to the shoreline (and partly responsible for the incredible scenery of these parks). The parks along East Coast and Gulf Coast are host to sandy beaches and barrier islands and coastal bays, lagoons, and estuaries that are important wildlife habitats. These coastline are also at risk of hurricanes and storms (East and Gulf Coasts). The West Coast has the risk of damaging storms and tsunamis.

Fig. 12-55. Map of the United States showing national park sites associated with coastal landforms and ocean environments. |

12.26

Impacts of Climate Change on Coastal Environments

Climate change is causing a wide variety of impacts on coastal environments including physical changes to the landscape and shallow nearshore settings, biological impacts, and societal impacts. The breadth and scope of climate change is too much to be presented here.In fact, many colleges with STEM programs are now offering courses and degrees specifically dedicated to the study of climate change. See https://climate.gov/ for a sample of information presented by NOAA. Below is a guide to some of those observable impacts, as well as how they will likely project into the future if little or nothing is done to mitigate the problems associated with human-induced climate change. Although natural fluctuations occur in the world climate, as illustrated natural cycles associated with ebb and flow or the Ice Ages, what humans have done to change the environment in the last 100 years is significant, and is of grave concern for the future of our planet. The baseline problem is the contribution of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere through consumption of fossil fuels, deforestation, agricultural activities, urban growth, and more. Below is a list of some of the known impacts of climate change on coastal environments.

- Sea level rise is caused by the melting of glaciers and expansion of the oceans water column as sea water heats up over time.

- Warmer oceans create a warmer atmosphere which, in turn, impacts the global atmospheric circulation system (impacting coastal regions).

- Landward migration of shorelines as sea level rises, flooding low-lying coastal area, also resulting in habitat loss.

- Higher sea levels will cause salt water to move into both coastal freshwater areas and intrude into groundwater aquifers, damaging water quality.

- A warmer atmosphere can hold more water, increasing the intensity of superstorms (hurricanes, typhoons, seasonal storms).

- Higher sea levels and stronger storms increase coastal erosion and sedimentation in coastal environments, increasing pollution.

- Stronger storms will increase the intensity of storm surges and coastal flooding.

- Infrastructure such as coastal levees, highways, bridges, landfills in coastal areas will be impacted by sea level rise and increase storm intensity.

- Climates are migrating toward the poles as the atmosphere warms.

- Reduction to elimination of sea ice with impacts both surface and deep ocean circulation, with possible shut down of ocean circulation currents.

- Thicker, warmer thermoclines shut down upwelling currents that provide nutrients to sea life in surface waters.

- Warmer water holds less oxygen, resulting in habitat loss, and displacement or replacement of species in coastal environmental settings.

- Increases carbon dioxide levels is sea water is causing acidification of seawater.

- Cold-water species are being stressed and displaced by warm-water species.

- Communities living in low-lying coast regions are being displaced as sea level rises, causing a host of social and health problems.

In short, climate change is now arguably the #1 concern of the world's scientific community. |

|