Northern Manhattan Island

The complex geology of Manhattan Island is best exposed in parklands along its northern end (Figure 16). Several major rock units comprise the stratigraphic section beneath this portion of the city: the Middle Proterozoic Fordham Gneiss, the Cambrian Manhattan Formation, and of the Cambrian and Ordovician Inwood Marble. Outcrops of these formations disclose the complex, northeastward-trending structure of the region. |

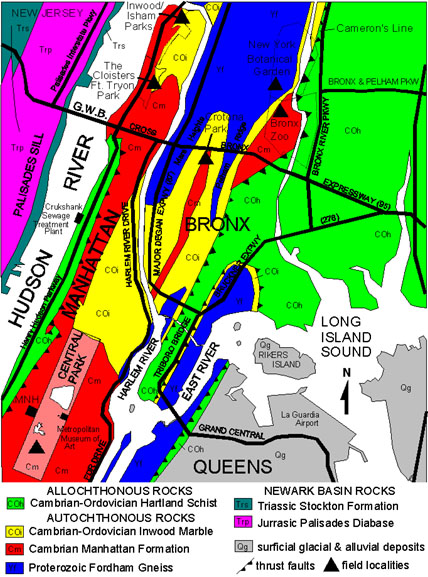

| Figure 16. Geologic map of northern Manhattan and The Bronx (modified after Schuberth, 1967). |

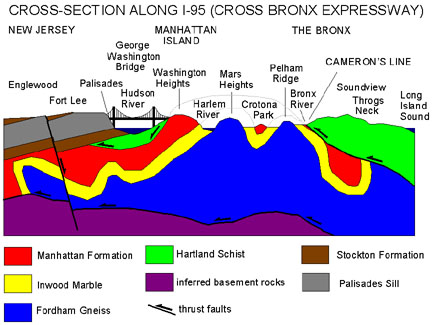

Figure 17 is a simplified cross section along I-95 extending from the Palisades of New Jersey eastward across the northern tip of Manhattan Island, to sites along the Cross Bronx Expressway. The complexity of the structure is a result of a series of great folds and the great thrust faults associated with the Taconic shear zone, Cameron's Line. To the east of this boundary, the Hartland Formation was, until recently, undifferentiated from the Manhattan Formation to the west. It is equivalent in age and very similar in physical appearance to the Manhattan Schist. Today, the Hartland Formation is considered to be comprised of oceanic crust and eugeoclinal materials that were highly metamorphosed and thrust westward during the accretion of the Iapetus terrane during the Taconic Orogeny.

|

| Figure 17. Simplified cross section of northern Manhattan and The Bronx along I-95 (including the George Washington Bridge and Cross Bronx Expressway). |

The differences in fracturing and weathering of each of the rock units is responsible for the lay of the land. The general shape of the landscape is related to the erosion of river valleys before and between periods of glaciation. Much of the modern landscape in Manhattan and the Bronx only has a thin veneer of soil developed after the most recent episode of glaciation. The influence of weathering on the landscape is perhaps best illustrated by the location of the Hudson River along the western margin of Manhattan and the Bronx. The Hudson River follows the unconformable boundary between the underlying crystalline basement rocks and the younger westward-dipping sedimentary and volcanic strata of the Newark Basin.

On Manhattan Island the weathering character of each of the metamorphic rock

units also influences the local topography. Driving northwestward along Harlem

River Drive, the roadway crosses the densely urbanized Harlem lowlands, underlain

by Inwood Marble. The marble is both softer and more soluble than the other

rock units, and therefore, is worn down closer to sea level. Continuing westward,

the roadway climbs an escarpment rising to Washington Heights, the highest area

on Manhattan Island. On the south side of the highway in Highlands Park, massive

exposures of schist and gneiss of the Manhattan Formation reveal the complex

faulted and contorted structure of the bedrock. The bedrock beneath Washington

Heights, the upland area on the eastern end of the George Washington Bridge,

also consists of the more erosion-resistant Manhattan Formation. A scenic location

to look at the Manhattan Formation in this area is around the The

Cloisters Museum in Fort Tryon Park.

Follow these links to Highlands geology sites in Manhattan:

1. Central Park

2. Cloisters Museum and Fort Tryon Park

The Bronx

As discussed previously, there are many spectacular exposures of bedrock along

the highways throughout the Bronx, but they are nowhere safe for casual study.

(It is illegal to stop; but as many Bronx Expressway travelers know, major traffic

jams are a frequent occurrence. During such delays there is typically plenty

of time to contemplate the highway outcrops from your car window!) Fortunately,

there are many exceptional places to study the geology in the Bronx.

Figures 16 and 17 show the general character of the basement structure of the

Bronx: a series of folded and faulted metamorphic rocks. Running north to south

across the Bronx in the vicinity of the Bronx River is Cameron's Line, the thrust-faulted

suture between the more "autochthonous" basement rocks and the "allochthonous"

rocks of the Iapetus terrane accreted onto North America during the Taconic

Orogeny. The trace of Cameron's Line is extremely difficult to map other than

on a large scale. This is because large fault systems can be amazingly complex,

consisting of multiple thrust sheets stacked in close succession. It is much

easier to draw a generalized line on a map than it is to walk and drive along

between outcrops, and actually trace a complex fault. In addition, the rocks

of the Manhattan Formation to the west, and the Hartland Formation to the east

are essentially of similar age and mineralogical composition. The Hartland Formation

generally displays a greater degree of metamorphic alteration. It would take

many geologists many years to map out the details.

The geologic map in Figure 17 is extremely simplified. The rocks in the central and eastern portion of the Bronx are tightly folded and probably broken by numerous thrust faults. However, the similar character of the schist and gneiss throughout the area make detailed mapping practically impossible. Although Cameron's Line may be well defined throughout portions of Connecticut, the location of the suture is poorly defined within the Bronx. The north-to-south trace of the Bronx River possibly defines one trace of this irregular boundary. To the east of the Bronx River, the bedrock consists of the gneiss and schist of the Hartland Formation. Follow these links to Highlands geology sites in the Bronx:

3. Inwood Hill Park/Isham Park

4. Crotana Park

5. New York Botanical Gardens and Bronx Zoo Park

6. Pelham Bay Park

7. Staten Island Serpentinite

| Return to the Highlands Province Main Page. |