Regional Geology of North America |

|

Colorado Plateau |

Click on images for a

larger view. |

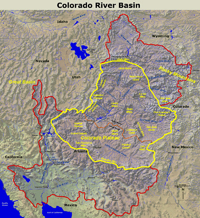

| The Colorado Plateau is an elevated region sandwiched between the Southern Rocky Mountains (to the east) and the Great Basin/Basin and Range province (to the south and west)(Figure 130). The region is famous for its high desert scenery preserved in a large number of national parks. |

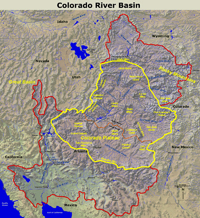

The entire Colorado Plateau region has risen nearly a mile in the last 20 million years; this has exposed the region to extensive erosion. The Colorado Plateau is actually a series of erosionally-dissected plateaus with elevation tops ranging from 5,000 to 11,000 feet. There are several small mountain ranges within the Colorado Plateau. The highest elevation of 12,700 feet is found in the La Sal Mountains of Utah. The lowest elevation is 2,000 feet in the Grand Canyon of Arizona. The Colorado River and its tributaries have carved many deep and narrow gorges across the region (Figures 135 and 136).

Nearly 200 named sedimentary rock formations of nearly all geologic ages crop out in canyons, escarpments, mesas, and buttes throughout the Colorado Plateau region. The physical properties of the different rock units give rise to the variety of colors, shapes, and erosional characteristics. Mountain ranges of volcanic origin across the region include the La Sal Mountains, Henry Mountains, Abajo Mountains, and Boulder Mountain in Utah. Mountains on the Colorado Plateau in Arizona include the Chuska Mountains and the San Francisco Mountains. |

Fig. 135. Map showing the location of national parks and monuments on the Colorado Plateau. |

Fig. 136. Map of the greater Colorado River Basin which encompasses the Colorado Plateau. |

Landscape Features on the Colorado Plateau in Utah

One of Utah's claim to fame is its 5 national parks: Arches, Canyonlands, Capitol Reef, Bryce Canyon, and Zion. However, there is much more to see in Utah if you like high desert canyon country. Arches National Park is famous for its natural arches sculpted into thin finds of Jurassic-age Entrada Sandstone (Figure 137). Canyonlands National Park encompasses the rugged canyon country surrounding the confluence of the Green and Colorado Rivers, the principle rivers dissecting the Colorado Plateau (Figure 138 and 139). The Colorado River drains from the high ranges of Colorado before entering Colorado Plateau Country near Grand Junction. The Green River descends out of Wyoming, cutting a path around the east end of the Uinta Mountains before entering the Colorado Plateau at Dinosaur National Monument on the Colorado-Utah Border (Figure 140). The combined rivers become the principle water supply for the southwestern United States. |

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 137. Delicate Arch in Arches National Park is an icon for both the State of Utah and the National Park Service. |

Fig. 138. Confluence of the Green and Colorado Rivers in the heart of Canyonlands National Park, Utah. |

Fig. 139. The Needles district in Canyonlands National Park, Utah is famous for erosional features of the Permian-age Cedar Mesa Sandstone. |

Fig. 140. The Green River cuts through a monoclinal fold in Dinosaur National Monument, Colorado/Utah border. |

|

| The San Juan River drains from the high country of the San Juan Mountains in Colorado into northern New Mexico, then crosses into southern Utah where it drains into Lake Powell on the Colorado River. Along the way the San Juan River has carved a meandering path called the" Goosenecks of the San Juan" (Figure 141). The Gooseneck reveal that the San Juan River was probably a meandering stream on a broader flood plain before regional uplift increased the stream gradient, forcing the river to carve down into its floodplain. The regional uplift of the Colorado Plateau began about 6 million years ago. The uplift increased the stream gradient in the region, and stream downcutting followed. This phase of uplift and erosion is responsible for nearly all the magnificent landscape features on the Colorado Plateau. Near Mexican Hat (name for both a town and its landmark feature) the San Juan River cuts through late Paleozoic strata exposed in the Riplee Anticline (Figure 142). North of Mexican Hat, Utah Highway 95 passes through the "Valley of the Gods" before it climbs the massive escarpment of the Permian-age Cedar Mesa Sandstone (Figure 143). The Cedar Mesa Sandstone is host to several amazing natural bridges and canyons in Natural Bridges National Monument (Figure 144). |

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 141. The "Goosenecks of the San Juan" are a series of incised river meanders on the San Juan River, southern Utah. |

Fig. 142. Mexican Hat, a famous natural landmark, with the Riplee Anticline in the distance, southern Utah. |

Fig. 143. Utah Highway 95 descends into the Valley of the Gods, an escarpment along the San Juan River valley. |

Fig. 144. White canyons carved into the Permian Cedar Mesa Sandstone in Natural Bridges National Monument, Utah. |

|

| The Kayenta Formation and Navajo Sandstone (both Lower Jurassic) form high escarpments and deep canyons wherever they crop out on the Colorado Plateau. The Kayenta Formation is mostly a pink or buff-orange sandstone; the overlying Navajo Sandstone typically forms white cliffs. Together they are the rocks that form Rainbow Bridge and many of the high cliffs along Lake Powell and Glen Canyon (below Glen Canyon Dam) (Figures 145 to 147). The Kayenta and Navajo formations are also featured in Zion National Park and Capitol Reef National Park (Figures 148 and 149). |

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 145. Rainbow Bridge National Monument on Lake Powell with Navajo Mountain in the distance, located in southern Utah. |

Fig. 146. Navajo Mountain, southeast of Lake Powell in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah and Arizona. |

Fig. 147. Glen Canyon Dam on the Colorado River is within Glen Canyon National Recreation area (near Page, Arizona). |

Fig. 148. White cliffs of Jurassic Navajo Sandstone over red Kayenta Formation dominates the canyon scenery in Zion National Park, Utah. |

|

|

| Fig. 149. Panoramic view of the Waterpocket Monocline (a great fold in Mesozoic-aged sedimentary rock formations), as seen from the Strike Valley Overlook in Capitol Reef National Park with the Henry Mountains in the distance to the east (in central Utah). The Henry Mountains were the last "discovered" and named mountain range in the United States by the Powell Expedition of 1869. The consist of the eroded remnants of mid-Tertiary igneous intrusions (laccoliths). |

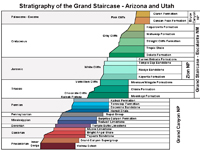

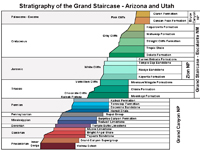

Stratigraphy of the Grand Staircase

The name Grand Staircase has been used to describe the step-like nature of cliff-forming escarpments on the Colorado Plateau. The Grand Staircase starts at the Colorado River in Grand Canyon National Park (about 2,000 feet in elevation) and climbs up the stratigraphic section through Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, and Zion an Bryce Canyon National Parks (Figure 150). Some rock units are mostly soft shales and mudstone and generally weather to form slopes. Hard limestone and sandstone formations tend to form clifts and cap escarpments and plateau tops, such as the Kaibab Limestone capping the Kaibab Plateau around the Grand Canyon. Every rock formation has a distinct appearance associated with their composition and origin. However, cliff-forming formations have been named by early settlers in the region including the Chocolate Cliffs (Moenkopi Formation), Vermillion Cliffs (Moenave/Kayenta Formations), White Cliffs (Navajo Sandstone), Gray Cliffs (Cretaceous formations), and Pink Cliffs (Claron Formation). See more at Stratigraphy of the Colorado Plateau. |

Fig. 150. Stratigraphy of the Grand Staircase, Arizona and Utah. |

High Plateaus of Central Utah

The western side of the Colorado Plateau consists of a series of high plateaus with elevations ranging from 8,000 to over 11,000 feet and include the Sevier, Aquarius, Paunsaugunt, Kaiparowitz, and Markagunt Plateaus, and Boulder Mountain (a volcano).

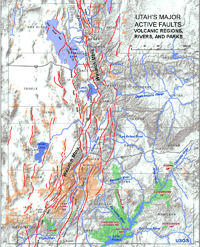

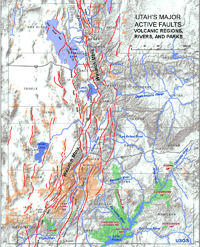

The western side of these plateaus transition into the Wasatch Mountains along the border of the Colorado Plateau and the Great Basin to the west. The boundary region has many active earthquake faults that are responsible for the rugged topography of the Transition Zone between provinces (Figure 151). The fault zones are also associated with regional volcanic activity during the Pleistocene Epoch. Ancient lake deposits of Eocene-age Claron Formation now cap the highest part of the plateaus (Figures 152 and 153). |

Fig. 151. Utah faults and rivers. Fig. 151. Utah faults and rivers. |

|

|

| Fig. 152. The Eocene-age Claron Formation forms the Pink Cliffs and caps the Paunsaugunt Plateau at Bryce Canyon National Park. |

Fig. 153. Badlands in the Eocene-age Claron Formation in Cedar Breaks National Monument located along the western escarpment of the Markagunt Plateau, Utah. |

Colorado Plateau in Arizona

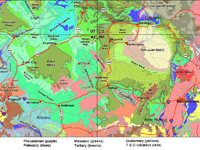

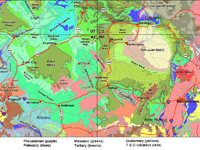

The Colorado Plateau extends into northern Arizona—most of the region in Arizona is on the Navajo and Hopi Indian Nation lands, mostly remote, often rugged high-desert country (Figure 154). The region is characterized by broad plains and plateaus. The physiography of the region is primarily defined by physical characteristics of the bedrock geology (Figure 155). Regional uplift has resulted in erosion that has carved carved canyons, escarpments along the Colorado River and its tributaries. In addition volcanism and tectonic forces have shaped the landscape in Tertiary time to the present. Precambrian and Paleozoic rocks are exposed in the Grand Canyon and the Defiance Uplift region. Elsewhere, Permian, Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous sedimentary rock formations form escarpments and associated plateaus across the region. |

Fig. 154. Arizona physiography. |

Fig. 155. Geologic Map of the southern Colorado Plateau Region showing rock units by geologic age and composition, volcanic, faults, and folds. |

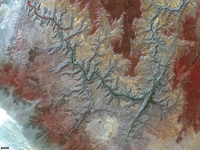

The Grand Canyon

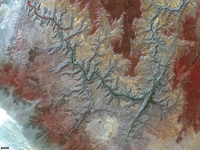

The Grand Canyon is the largest and deepest canyon in the United States. The canyon cuts through the Kaibab Uplift (or Kaibab Plateau) for a distance of almost 300 miles. It varies from 4 to 16 miles wide, and about 1 mile deep (Figure 156). The Grand Canyon starts where the Colorado in Marble Canyon joins the Little Colorado River (Figure 157). The lower canyon ends where it joins the Virgin River in Lake Mead. Crystalline basement rocks, sedimentary rocks, and volcanic rocks of Precambrian age crop out along the Inner Gorge (Figure 158). Flat-lying sedimentary rock formations of Cambrian to Permian age form the Paleozoic section of the Grand Staircase (see Figure 159). The Colorado River and its tributaries have carved the Grand Canyon as the Kaibab Uplift has risen over the past 6 million years. The Kaibab Uplift is an erosionally dissected plateau. The South Rim is averages about 6,800 feet, the North Rim averages about 8,300 feet, the Colorado River averages about 2,200 feet (Figures 160 to 161). |

Fig. 156. Satellite view of the Grand Canyon cutting through the Kaibab Uplift (Plateau) in northern Arizona. |

Fig. 157. Marble Canyon Bridge located just downstream from Lees Ferry, Arizona and upstream of the Grand Canyon. |

|

|

|

|

Fig. 158. Grand Canyon's Inner Gorge near Phantom Ranch as seen from the Bright Angel Trail in Grand Canyon National Park.

|

Fig. 159. South Rim view of the Colorado River and Kaibab Plateau on the North Rim in Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. |

Fig. 160. Rock fins and butte in the Kaibab Limestone at Roosevelt Point along the North Rim of Grand Canyon National Park. |

Fig. 161. Lava flows poured into a dammed the lower Grand Canyon many times during the Pleistocene Epoch. |

|

Permian escarpments

The majestic buttes and mesas of Monument Valley and Canyon De Chelley formed erosion of the Permian-age De Chelley Sandstone (Figures 162 and 163). Canyon de Chelley is carved into The Defiance Uplift—a north-south trending anticline extending over 100 miles from the Four Corners region to Interstate 40, just inside the Arizona border (Figure 164). The southern boundary of the Colorado Plateau is the Mogollon Rim, an escarpment capped by Permian-age Kaibab Limestone and Coconino Sandstone, and locally by Tertiary basalt flows. The escarpment rises about 3,000 feet above low lands south of the rim in the mountainous “transition zone" between the Colorado Plateau and the Basin and Range (example is at Sedona, Arizona, Figure 165).

Triassic plains and badlands

The Painted Desert is a region underlain by the brightly colored mudstone and shale of the Triassic-age Chinle Formation, forming badlands topography in the high desert climate (Figures 166 and 167). The Chinle Formation is host to fossiliferous beds exposed in Petrified Forest National Park and throughout the Painted Desert region.

Mesozoic escarpments and Plateaus

High, steep cliff-sided escarpments form along exposures of Kayenta, Navajo, and Entrada Sandstone formations (Figures 168 to 169). Black Mesa is a high plateau region underlain by Cretaceous-age sedimentary rocks that have abundant coal resources. |

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 162. Remnants of Permian sedimentary rocks exposed in Monument Valley on the Navajo Reservation, Arizona. |

Fig. 163. Spider Rock in Canyon de Chelley National Monument, eastern Arizona. |

Fig. 164. A monoclinal fold in Permian strata along the Defiance Upwarp near Window Rock, Arizona. |

Fig. 165. Cliffs and buttes around Sedona, Arizona are part of the southern escarpment of the Colorado Plateau called the Mogollon Rim. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 166. Painted Desert in Triassic Chinle Formation exposed in northern Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona/New Mexico border. |

Fig. 167. Adeii Eechii Cliffs are an escarpment of Jurassic sandstones over Triassic shale badlands located between Flagstaff and Tuba City, Arizona. |

Fig. 168. Anasazi ruins are in an alcove in Kayenta Formation beneath Navajo Sandstone in Navajo National Monument, Arizona. |

Fig. 169. Coal Mine Mesa near Tuba City, Arizona has a cap of Cretaceous-age Dakota Formation over cliffs of Jurassic Entrada Sandstone. |

|

Igneous Rock Features on the Colorado Plateau

Volcanic features on the Colorado Plateau in Arizona have formed in stages through Tertiary time to the present. Erosional remnants of ancient volcanic features stand out in stark dark contrast to the surrounding brightly colored sedimentary rocks. Three regions where igneous rocks crop out include the Navajo, Hopi Buttes, and San Francisco Volcanic Fields.

The Navajo Volcanic Field includes scattered features in Four Corners Region extending from near Kayenta, Arizona into the Carrizo Mountains and region surrounding the Four Corners (AZ, NM, CO and UT). Volcanic vents are also scattered around in the Chuska Mountains (northwest Arizona) (Figure 170).

The Hopi Buttes consist of eroded remnants of igneous dikes, stocks, volcanic breccia, and diatremes that formed about 25 to 30 million years ago. The Hopi Buttes Volcanic Field northeast of Holbrook, Arizona consists of eroded remnants of volcanic features that formed between 8.5 to 4.2 million years ago (Figure171).

The San Francisco Volcanic Field is located north and west of Flagstaff, Arizona and contains 600 volcanoes ranging in age from about 6 million years to the youngest less than a 1,000 years. Humphreys Peak (elevation 12,633 feet) is a large stratovolcano near Flagstaff and is Arizona’s highest peak (Figure172). Wupatki-Sunset Crater National Monument is host to the youngest volcano and lava flows about 900 years old (Figure 173). |

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 170. A volcanic stock (a kimberlite) near Kayenta, is part of the Navajo Volcanic Field, northeastern Arizona. |

Fig. 171. Hopi Buttes are eroded remnants of a Miocene-age volcanic field in the Painted Desert region of Arizona. |

Fig. 172. Humphreys Peak, elevation 12,625 feet, is Arizona's highest peak in the San Francisco Volcanic Field. |

Fig. 173. Sunset Crater, a cinder cone with lava flows that formed about 900 years ago in the San Francisco Volcanic Field. |

|

Colorado Plateau in Colorado

The Colorado Plateau extends partly into western Colorado (Figure 174). Along Interstate 70, the transition from the Rocky Mountains to the Colorado Plateau occurs near Glenwood Springs, Colorado. West of Glenwood Springs the Colorado River canyon expands into the broad Grand Valley near Grand Junction, Colorado. (Note: in 1921, Congress changed the name of the Grand River to Colorado River!)

On the north side of the Grand Valley are the Book Cliffs, an escarpment to the Roan Plateau.The Roan Plateau overlies the Piceance Basin, a structural downwarp filled with early Tertiary-age sediments that underlies the region between northwestern Colorado to Green River in northern Utah. The Book Cliffs are an escarpment of the Green River Formation (Eocene) which are host to massive shale-oil resources (estimated to be more than all oil reserves in the OPEC nations). Those deposits, however, are not economically feasible to extract.

On the south side of the Grand Valley is an escarpment composed of Mesozoic-age rock formations borders the south side of the Colorado River Valley, much of it is preserved in Colorado National Monument (Figures 175 and 176). The escarpment is the northern border of the Uncompahgre Plateau, an expansive upland region with elevations averaging about 9,500 feet. The Uncompahgre Plateau borders the San Juan Mountains to the southeast. Most of the bedrock exposed in the Colorado Plateau south of the Colorado River is Cretaceous sediments of the Mancos Shale and overlying Mesa Verde Formation.

Mesa Verde is another upland plateau located the southwestern corner of Colorado. The Plateau is host to Mesa Verde National Park (Figures 177 and 178). Nearby is Hovenweep National Monument (near Sleeping Ute Mountain, a volcanic laccolith). Both parks preserve notable ruins from the Anasazi (ancestral Pueblo Cultures). |

Fig. 174. Map of western Colorado showing the border between the Rocky Mountains Province and the Colorado Plateau Province. |

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 175. Escarpments of Mesozoic-age sedimentary rocks in Colorado National Monument and the Colorado River Valley near Grand Junction, Colorado. |

Fig. 176. A large monoclinal fold along the north side of the Uncompahgre Plateau and the south side of the Grand Valley near Grand Junction in Colorado National Monument. |

Fig. 177. Ancient Anasazi cliff dwellings are preserved in an alcove in overhanging Cretaceous-age sedimentary rocks in Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado. |

Fig. 178. A road cut along the road to Mesa Verde National Park exposes coal beds and river sand beds in the Cretaceous Mesaverde Formation. |

|

Colorado Plateau in New Mexico

The Colorado Plateau extends partly into northwestern New Mexico. The San Juan River is the main river drainage in the region. The San Juan Basin is a structural basin that encompasses most of the New Mexico portion of the Colorado Plateau (see Figure 155). The region around Farmington, New Mexico is an old oil and gas producing basin. The region is perhaps most famous for Chaco Canyon National Historic Park, a park that encompasses several ancestral Pueblo Indian (Anasazi) cities, long abandoned, along Chaco Wash, a tributary of the San Juan River (Figure 179).

Ship Rock is a prominent natural landmark that rises from the San Juan Basin along the New Mexico/Arizona border. Shiprock is the eroded remnant of an ancient volcano—only the volcanic stock with wall-like radiating dikes remain (Figure 180). It is an outlier of the Navajo Volcanic Field that extends into Arizona.

El Mal Pais National Monument and El Morro National Monument are parks along the southern border of the Colorado Plateau. El Mal Pais (Spanish for "badlands") is a valley that was flooded by basaltic lava flows from eruptions from the Zuni-Bandera Volcanic Field (Figure 181). Volcanic eruptions have occurred as recently as 3,000 years ago. El Morro National Monument is also host to a historic natural landmark called Inscription Rock. Plunge pools at the base of waterfalls draining from Inscription Rock was a source of water along ancient and historic trails across the region. Ancestral and modern Indians, early Spanish explorers, Army soldiers, and early settlers all carved messages into the soft Aztec Sandstone that makes up the rock (Figure 182). |

| https://gotbooks.miracosta.edu/geology/regions/colorado_plateau.html 1/20/2017 |

|

|

|

|

Fig. 151. Utah faults and rivers.

Fig. 151. Utah faults and rivers.