Introduction to Physical Geology |

Chapter 1 - Introduction to Physical Geology |

Defining the Science of GeologyGeology is the study of the Earth. The scientific study of the origin, history, and structure of the Earth. The structure of a specific region of the Earth's crust. And, the scientific study of the origin, history, and structure of the solid matter of a celestial body. Two main branches of geology include:Physical geology—a branch of geology concerned with understanding the composition of the earth and the physical changes occurring in it, based on the study of rocks, minerals, and sediments, their structures and formations, and their processes of origin and alteration. Historical geology—the study of the composition, relative positions, etc., of rock strata in order to determine their geological history. Historical geology is dependent on concepts and order of events related to deep time, as defined by a geologic time scale (a measured scale of time going back in time in named steps covering thousands, millions, and billions of years; geologic time is discussed below). Geologists (individuals who study geology) are also involved in the sciences of: Hydrology—the branch of science of the earth's water resources, especially its movement in relation to land. Oceanography—the branch of science concerned with the physical and biological properties of the world's oceans, seas, and coastal marine environments. Meteorology—the branch of science concerned with atmospheric processes and phenomena, including weather and climate. Astronomy—the branch of science that concerns celestial objects in space, and physical Universe as a whole. The physical environments of other planets and objects in the Solar System provide insights into what is happening here on Earth (utilizing space-based observation of the Earth's systems (earth, water, and air). (Note that astronomy and astrology are not the same. Astrology is the metaphysical study of the movement of celestial objects and how their motions are used to interpret their influence on human affairs. Astrology is not discussed in this course.) Engineering and Environmental Geology—as society and populations grow, the demand for geologist's input into nearly all aspects of civil engineering, urban planning, natural resource management, and national require special knowledge related to geology and related fields. Agronomy—science applied to the study of soils and crop management. |

What do geologists do?• Geologists study earth processes associated with natural disasters: floods, earthquakes, landslides, volcanic eruptions.• Geologists explore and manage resources: oil & gas, water, metals, rock byproducts. • Geologists work in environmental fields: climate change, waste management, natural resource protection. • Geologists work in construction and engineering: archeology, foundations, urban planning, and coastal and marine issues. • Geologists serve in national security, including Federal, state, and local governments and are involved in public health, safety, and logistics. • Geologists study ocean basins, glaciers, and are involved in space exploration programs. • Geologists work in education: schools and universities, parks, and museums. |

| Many Federal and State organizations employ geologists. | |||

| Name of Federal Agencies | Website | ||

| USGS US Geological Surrey |

www.usgs.gov |

|

|

| NOAA National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration |

www.noaa.gov | ||

| BLM US Bureau of Land Management |

www.blm.gov | ||

| NPS US National Park Service |

www.nps.gov | ||

| NASA National Aeronautical & Space Administration |

www.nasa.gov | ||

| USDA US Department of Agriculture |

www.usda.gov | ||

| DOD US Department of Defense |

www.defense.gov | ||

| DOE US Department of Energy |

www.doe.gov | ||

| EPA US Environmental Protection Agency |

www.epa.gov | ||

| CDC US Center for Disease Control |

www.cdc.gov | ||

The Scientific MethodThe scientific method is how scientific ideas are tested and validated and applies to research conducted in nearly all professions.The scientific method involves: • Collection of data and observations leads to multiple hypotheses (educated guesses). • Each hypothesis is rigorously tested and it fails (rejected) or passes (and become a theory). • Tests/experiments must be thoroughly researched and accurately reported. • Tests/experiments result must be reproducible. Define science, observation, hypothesis, fact, theory, scientific law, and scientific methods. Science is the systematic knowledge of the physical or material world gained through observation and experimentation. The overall goal of science is to understand how the natural world works. The fundamental assumption of science is that the natural world behaves in a consistent and predictable manner. The scientific method involves the observation of phenomena, the formulation of a hypothesis concerning the phenomena, experimentation to demonstrate the truth or falseness of the hypothesis, and a conclusion that validates or modifies the hypothesis. Observation is the act of noting and recording something, such as a phenomenon, with instruments, in order to gain information. An example is the collection for data for temperature, oxygen levels, and pollutants in seawater at different depths in a harbor to monitor water quality for sea life protection. A fact is knowledge or information based on real occurrences; something demonstrated to exist or known to have existed. A hypothesis is a tentative explanation for an observation, phenomenon, or scientific problem that can be tested by further investigation. An example of the testable hypotheses: Observed high levels of certain types of bacteria in seawater samples from a harbor might be linked to an influx of raw sewage leaking from a nearby sewage treatment facility. A theory is a set of statements or principles devised to explain a group of facts or phenomena, especially one that has been repeatedly tested or is widely accepted and can be used to make predictions about natural phenomena. Note that in science the word theory means something far more certain and concrete than the popular use of the word, which we can define as an assumption based on limited information. Established scientific theories are based on vast amounts of information and knowledge, giving us high confidence that they are correct. Science is dynamic. As new information becomes available (based on new methods of analysis, observations, experimentation, facts) scientific theories can be modified, expanded, or even rejected as newly tested information and ideas become available. |

Making assumptions can be a dangerous thing!An assumption is a thing or idea that is accepted as certain to happen, without proof. Misinterpreted observations can easily be used as proof or evidence in helping to establish a fact or resolve the truth of a statement. However, assumptions are often used as guiding principles in decision making when proof or facts are not resolved or accepted. Classic assumptions in history include ideas such as the Earth is flat, or the Earth is the center of the Universe. Throughout history, political, religious, economic special interests, and strongly-held societal beliefs have been used as underlying assumptions; sometimes they hold true, others are often proven wrong by new scientific evidence. The term educated guess (a hypothesis based on some related knowledge and experience, and therefore likely to be correct) may be no more than an assumption. |

Early Contributions to GeologyRecords of geologic observations are known from antiquity, including from ancient Egypt, Greece, China, Rome and other cultures that needed resources and basic engineering to mine minerals and build cities. However, without the knowledge available to the world today, interpretations of much that was observed in the past was inferred through the filter of religious ideology. Although many thousands of individuals have contributed important ideas, several people in history stand out for making important early contributions, often at the risk of their own lives and well-being.Early investigations in geology focused on describing landscape features, classifying rocks, minerals, geologic features, and mapping. As explorers returned with discoveries and maps from missions around the world, libraries and museums began to fill with enough materials for people to begin to recognize patterns in data. Most of the early works in modern geology came out of Europe's scientific community. AristotleOne of the oldest records concerning the origin of the Earth and basic geologic concepts are attributed to Aristotle in the 4th Century BC who made critical observations the slow rate of geologic processes changing the landscape. He noted that changes took place at rates much slower than can be observed in a single life time. Although rather simplistic, Ancient Greek philosophy observed the material world consisting of 5 elements that included earth, air, fire (plasma), water, and “aether” (an unobservable unknown force), and that interactions between these material forces accounted for all that was observable in the world (Figure 1-7). |

Fig. 1-7. Lava flowing into the sea illustrates the Aristotelian material elements of earth, wind, fire, and water. |

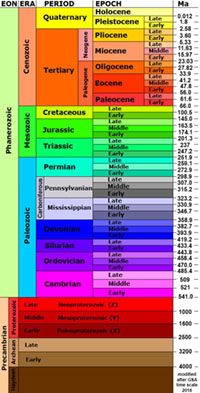

Understanding Geologic TimeGeological time refers to vast periods of the time, measured in thousand, millions, and billions of years (Figure 1-8). Named subdivisions of geologic time periods are often used to describe the physical formation and development of the Earth (especially prior to human history). Geologic time also applies to the age and history of the Universe. Geologic time and associated knowledge regarding the age of the Earth and all matter in the Universe are essential components of all modern sciences.Evolution of the Concepts Related To Geologic Time Applied To Earth HistoryAt the time of Galileo in the 16th Century, the general knowledge of the age of the Earth was interpreted by the biblical Genesis story and associated discussions by Greek and Roman philosophers. Early investigations in geology focused on describing landscape features, classifying rocks, minerals, geologic features, and mapping. As explorers returned with discoveries and maps from missions around the world, libraries and museums began to fill with enough materials for people to begin to recognize patterns in geologic data. Most of the early works in modern geology came out of Europe's scientific community. Although many thousands of individuals have contributed important ideas, several people stand out for making important early contributions, often at the risk of their own lives and well-being. The notion that the Earth was old (measured in billions of years) has not been all that popular with some religious organizations throughout the ages.Early investigations in geology focused on describing landscape features, classifying rocks, minerals, geologic features, and mapping. As explorers returned with discoveries and maps from missions around the world, libraries and museums began to fill with enough materials for people to begin to recognize patterns in data relating to the chronology of events in Earth's history. Most of the early works in modern geology came out of Europe's scientific community. Although many thousands of individuals have contributed important ideas, several people stand out for making important early contributions, often at the risk of their own lives and well-being. Leonardo Da VinciAlthough fossils have been marveled at throughout history, it was heresy to describe them as ancient life forms (for instance, Leonardo Da Vinci believed fossils were ancient life forms, older than the stories in the biblical book of Genesis, but he only wrote about it in secrecy).A fossil is a remnant or trace of an organism of a past geologic age, such as a shell, skeleton or leaf imprint, embedded and preserved in the Earth's crust. The fossils found in ancient layers of strata appear unique to rocks of similar age, wherever they occur. The collective knowledge of fossil evidence from around the world is referred to as the fossil record, and follows a time line through Earth's history. Nicolas StenoIt was was a Danish Catholic bishop, Nicolas Steno (1638-1686), who first promoted science of the origin of fossils and the basic geologic principles associated with the science of stratigraphy.The Science of StratigraphyStratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the systematic study of bedded rock layers and their relations in time and the study of fossils and their locations in a sequence of bedded rocks. A stratum is a bed or layer of sedimentary rock having approximately the same composition throughout (plural is strata). For example, Figure 1-9 shows strata exposed in the Grand Canyon. Each of the rock layers exposed in the Grand Canyon represent rocks that formed in different periods in the geologic past. Oldest rocks are at the bottom of the canyon; youngest are at the canyon rim at the top. Figure 1-10 illustrates a closer view of strata exposed in a sea cliff. Rock layers can have many different colors and physical characteristics related to the conditions when they formed.James HuttonA Scottish physician, James Hutton (1726-1797) studied rocks and landscapes throughout the British Isles and promoted uniformitarianism. Uniformitarianism is a theory that all geologic phenomena may be explained as the result of existing forces having operated uniformly from the origin of the Earth to the present time. Hutton's theory of uniformitarianism basically states states that the physical, chemical, and biological laws that operate today have also operated in the geologic past. It is commonly summarized: "The present is key to the past."Hutton fearlessly debated that the Earth was very old, measured in millions of years rather than thousands of years as promoted by the religion organizations of his times. Many scientists of his time promoted a theory of catastrophism. Catastrophism is a theory that major changes in the earth's crust result from catastrophes rather than evolutionary processes. The theory of catastrophism was more in line with religious doctrine common in the 17th and 18th centuries. It is interesting that today, uniformitarianism still applies to most geologic and landscape features, but discoveries have show that the Earth, or large regions of it, have experience great catastrophes, such as asteroid impacts, great earthquakes, super storms, great floods, or volcanic events. However, these events can be scientifically viewed within the greater context of modern geology. Uniformitarianism explains how observable processes taking place over long periods of time can change the landscape. Examples include:

James Hutton also contributed to a theory of rock formations. A rock formation is the primary unit of stratigraphy, consisting of a succession of strata useful for mapping or description. A rock formation typically consists of a unique lithology (rock type) that has a relatively defined geologic age and is considered mappable (occurs throughout area or region, both on the surface and in the subsurface). The correlation of rock formations (and the fossils they contain) from one region to another lead to the development of the geologic time scale (Figure 1-8,). William SmithWilliam Smith (1769–1839) used Hutton's theories to create the first geologic map of strata exposed throughout the British Isles. William Smith's map named Delineation of the Strata of England and Wales with part of Scotland published in 1815 was the first geologic map of an entire country (Figure 1-13). As nations began to understand the importance of geologic mapping for evaluating their natural resources, the science of geology began to grow. Once researchers had access to the distribution of materials and landscape features, they began to try to understand how and why landscape features like mountain ranges formed. What could explain the distribution of continents and oceans around the world? Why were some regions rich in certain kinds of mineral resources and others were not? |

Fig. 1-8. The geologic time scale provides names to a chronology of established periods of time in the history of Earth and the Universe —time periods range from thousands, millions, and billions of years. Note that Ma on this chart is an abbreviation for millions of years ago.  Fig. 1-9. Rocks exposed in the Grand Canyon of Arizona range in age from 2.8 billion years old to some recently formed volcanic rocks.  Fig.1-10. Strata (layered rocks) exposed in a sea cliff are part of name rock formations in the vicinity of Encinitas, California. Steno's concepts related to strata and stratigraphy are discussed in more detail in Chapter 3 and following chapters.  Fig. 1-11. William Smith's geologic map of 1815 was the first attempt to map an entire country. (British Museum of Natural History) |

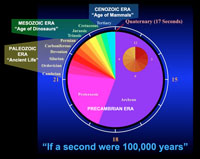

Geologic Time ScaleThe term geological time is used to describe the time of the physical formation and development of the Earth (especially prior to human history). Geologic time also applies to the age and history of the Universe. Geologic time is an essential component in discussions relating to the evolution of life on Earth (discussed in Chapter 16).The geologic time scale is a chart that geologists have subdivided periods in Earth's history is measured periods spanning millions to billions of years (Figure 1-8). Segments of time periods have been named to help define the chronology of events (such as formation of mountain ranges), the formation of rock units (such as the age of a lava flow), the age of fossils, organizing geologic map units, and other purposes. The geologic time scale subdivides the whole of geologic time into named subdivisions of time: eras, periods, and epochs (largest to smallest respectively). For instance, the Mesozoic Era, is subdivided into the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous Periods, and these periods are each subdivided into named epochs. The geologic time scale used today has evolved through the past two centuries as new scientific discoveries have been made and new technologies for dating the age of earth materials have become available. The Geological Society of America provides a more detailed and the most recently revised version of the GSA Geologic Time Scale. The time scale is constantly being revised as new information from research provides more precise data about past geologic events studied from locations around the world. The geologic time scale is revised as new data becomes available. Geologists have subdivided periods in Earth's history is measured periods spanning millions of years (Ma). Segments of time periods have been named to help define the chronology of events (such as mountain range formation), the formation of rock units (such as the age of a lava flow), the age of fossils, organizing geologic map units, and other purposes. The primary arguments about the age of the Earth and the observable Universe have been resolved by the global scientific community, but paradigms have ways of shifting as new discoveries are made and new information becomes available, and those ideas are tested by scientific methods. Vast periods of time in Earth history are fundamental parts of understanding biological evolution of life on earth (paleontology), understanding genetics, particularly related to human evolution, and in astronomy explaining the vastness and age of the observable universe. Geologists have subdivided periods in Earth's history is measured periods spanning millions to billions of years. Segments of time periods have been named to help define the chronology of events (such as the uplift of mountain ranges), the formation of rock units (such as the age of a lava flow), the age of fossils, etc. Names of geologic time periods (like Cretaceous Period or Pleistocene Epoch) are used for organizing geologic map units, charting the age or petroleum-bearing rock layers underground, and perhaps hundreds of other purposes. Figure 1-12 illustrates the vast extent of geologic time, using a 24 hour time clock and portrays the passage of time as if a second were 100,000 years. This illustration is commonly used in introductory natural science courses. Figure 1-13 show major geologic and evolution-related events in geologic time. College courses in historical geology examine what is currently known about the age of the Earth and the events as they are known or inferred to have occurred. For this course, the name of geologic time periods are used to explain the age of when gem deposits formed, and where and how they occur in relation to other rocks and deposits associated with them. For example, some diamond deposits may have formed deep underground in the Precambrian Eon (billions of years ago), but were exposed by erosion, transported, and deposited in river gravel beds in the late Tertiary Period (only several million years ago). |

Fig. 1-12. If a second were 100,000 years - this classic diagram show the distribution of a different ages of time as if it were all squeezed into a 24 hour day. All of human history would fit in the last fraction of a second!  Fig. 1-13. The geologic time scale (generalized) showing selected highlights in evolution of life on Earth and selected significant geologic events in Earth history leading up to the present. |

Important Early Biologists Who Influenced Historical GeologyDuring the same period, there was an explosion of knowledge was happening in the world of biology. Swedish biologist, Carl Linnaeus (1707-1788) began the biological naming scheme of binomial nomenclature, establishing a logical way to chart and classify life forms. Taxonomy gave later scientists a means to classify both modern and ancient life forms. This helped Charles Darwin (1809-1882) to first propose and publish a theory of natural selection, a fundamental part of the greater theory of biological evolution. Evolution is an essential component to explaining the distribution life forms on the planet and the nature of fossils preserved in sedimentary rocks through the geologic ages.Evolution, in general terms, evolution means the gradual development or change of something, especially from simple to more complex forms (this may apply to living things, ideas, organizations, and technology). In the natural sciences, biological evolution is the process by which different varieties of living organisms developed and diversified from earlier forms during the history of the Earth. Paleontology is the study of ancient life forms (including microbes, plants, and animals) that existed in the geologic past. Fossils have been collected and studied from ancient time and have been a part of major museum collections for many centuries. The concepts of Earth history and the evolution of life on our planet important concepts for all the natural sciences Figure 1-15 is a brief summary of the evolution of life and major events in geologic history. This information is presented in a brief review of Earth history in Chapter 16. |

Fig. 1-14. Charles Darwin. |

The Geologic Age of the EarthThe age of the Earth currently accepted by the majority of the scientific community is approximately 4.56 billion years. On the geologic time scale the formation of the Earth occurred in early Precambrian time (see Figure 1-27). The origin of the Earth within the Solar System is discussed in detail in Section 1.37 below.Demand For Energy and Mineral Resources Supported Geologic Research in the 20th CenturyIt can be argued that all the science and discoveries of geology didn't matter much to the average citizen of the world until the discovery of the Spindletop Oil Field in 1901 (Figure 1-15). It was this discovery in Texas that started the modern Petroleum Industry. This happened the year before Henry Ford started his automobile company using internal combustion engines. These events initiated the growth and expansion of the world largest and most profitable industry—Big Oil. The demand for oil and mineral resources over the following century created opportunities for hundreds of thousands of people to be employed as geoscientists. However, the environmental impacts associated with consumption of fossil fuels (coal, oil, and gas) is now a paramount topic of conflicting discussion of needs and demands for energy to power modern society and the long-term implications for climate change around the world.The explosion of knowledge gained from the petroleum industry is only part of the story. The discovery of mineral resources, particular gold and other precious metals, as well as large diamond and other gem deposits have created rushes and boom-to-bust communities around the world. The advertising of the potential of finding gold in California in 1849 lead to one of the greatest human migrations in modern history, even though the amount of gold found in California is small compared with other locations around the world, particularly South Africa. Intense scientific exploration of the world's ocean basins and continental mineral resources of followed conquests after World Wars (I and II). Today, concerns about space science, water resources, conservation, and climate change and major factors advancing geologic research in the world today. |

Fig. 1-15. The Lucas Gusher in 1901 started the rush to the Spindletop Oil Field in Beaumont, Texas, beginning the great expansion of Big Oil. Fig. 1-15. The Lucas Gusher in 1901 started the rush to the Spindletop Oil Field in Beaumont, Texas, beginning the great expansion of Big Oil. Fig. 1-16. Ford assembly line. |

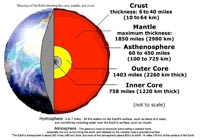

Structure of the Earth (an introduction)Discussion of the major components of Earth's physical environment involves discussion about the solid materials (rocks and landscapes), water resources, and its atmosphere. Each of these are discussed in more detail in following chapters. In cross-section, the Earth has a central core, a mantle, and the crust (Figure 1-17). A crust is the outermost solid shell of a rocky planet or moon, which is chemically distinct from the underlying mantle. |

Fig. 1-17. The internal structure of the Earth is divide into an inner and outer core, a thick mantle, and a thin crust on the surface. Other planets and moons also have cores, mantles and crusts, although they may be very different in composition for Earth. |

Dynamic Earth ProcessesPlanet Earth is dynamic—dynamic meaning that it is a system undergoing constant change involving natural processes or geologic activity, as well as interactions with extraterrestrial forces and object. Earth's atmosphere and oceans are constantly changing in an easily observable manner. However, the solid earth below us is also constantly changing but mostly in a way that is to slow to observe except is special rapid cases, such as with earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, landslides, collapse of glaciers, or even asteroid impacts (Figure 1-18). Changes in the landscapes and coastlines are also cause by major floods and/or storms. Each of these physical processes are discussed in following chapters. |

Fig. 1-18. Meteor Crater near Flagstaff, Arizona is asteroid impact site that happened about 50,000 years ago. Erosion eventually destroys or buries most impact craters, but many have been found. |

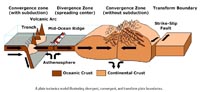

Plate Tectonics TheoryPerhaps the most significant modern achievement in the geological sciences is the advancement of Plate Tectonics Theory. Plate tectonics is a unifying collection of concepts that explains most things geological on Earth, and other planets and moons as well. The theory explains the structure of the Earth's crust and many associated phenomena as resulting from the interaction of rigid lithospheric plates that move slowly over the underlying more fluid mantle. (Figure 1-19; Plate Tectonics Theory discussed in greater detail in Chapter 5.) |

Fig. 1-19. Model representing essential concepts presented by Plate Tectonics Theory. |

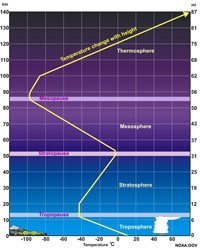

Earth's Atmosphere (An Introduction)An atmosphere is the gaseous mass or envelope surrounding a celestial body (including the one surrounding the Earth), and retained by the celestial body's gravitational field.The Earth's atmosphere is subdivided into levels (Figure 1-20): The troposphere is the lowest portion (up to about 6-8 miles [10-16 km]) where all weather takes place and contains about 80% of the air's mass and 99% of water vapor. The overlying stratosphere contains an abundance of ozone which absorbs ultraviolet radiation, protecting life on land and in the shallow ocean extends up to about 31 miles (50 km). The upper atmosphere (mesosphere and thermosphere) extends upward to the transition into space above about 60 miles (100 km) where the charged atomic particles of the solar wind begins to interact with atmospheric gases. |

Fig. 1-20. Structure of the atmosphere. |

Earth's Water: The Hydrosphere and CryosphereWater moves through the atmosphere (involving evaporation, transport, and precipitation), and flows both on the surface and underground on its journey back to the oceans. The collective actions of water migration is called the hydrologic cycle (Figure 1-21). The term hydrosphere is used to describe all the waters on the Earth's surface, such as oceans, lakes, rivers, and streams (discussed in Chapter 11). All life on Earth is associated with water. The term biosphere is used to describe all the regions of the surface, subsurface, and atmosphere of the Earth (and possibly other planets) occupied by living organisms. |

|

|

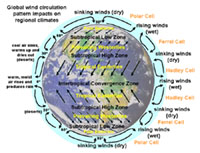

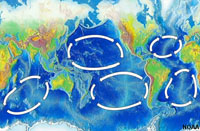

Earth's Oceans and Atmosphere Are LinkedSolar energy provides the heat that drives the motion in Earth's atmosphere and oceans. These motions are influenced by the rotation of planet on its axis that gives rise to the Coriolis effect, a force that causes deflection of currents in the oceans and atmosphere. The atmosphere moves in a system of great wind belts that moves the atmosphere (and weather systems) around the globe (Figure 1-22). Solar energy heats surface waters and warms the air. This causes evaporation and allows moisture to rise. As energy is released from the air, it allows precipitation to fall. The combination of solar heating and the motion of the global wind patterns drive ocean surface currents in large subtropical gyres (Figure 1-23). The net effect of the Earth's oceans and atmospheric systems is to move heat from the warm equatorial tropical regions to the cold polar regions. These processes are discussed in detail in Chapter 15. |

Fig. 1-22. Global wind circulation patterns impact regional climates and drive the large surface currents in the global ocean circulation system. |

Fig. 1-23. Five large gyres circulate surface waters in the global oceans. These rotating subtropical gyres are influenced by the patterns of atmospheric winds and the Coriolis effect. |

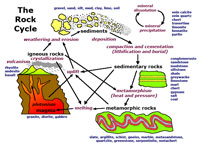

The Rock CycleThe rock cycle is a graphic and conceptual model used to illustrate common rocks and earth materials and the processes that form or change in the Earth’s crust over time (Figure 1-24). The rock cycle depicts the series of events in which a rock of one type is converted to one or more other types and then back to the original type (see the general classification of earth materials below). Both products (rocks and sediments) and processes (such as melting, cooling, erosion, deposition, metamorphism, remelting) are part of this idealized cycle. The passage of geologic time is the essential component, although some processes are much faster than others. Note that all these types of processes are taking place simultaneously, but at different locations on and within the crust. It is important to note that rock cycle processes occur on other rocky planets or moons but rates may vary due to the presence (or lack of) atmospheric gases or fluids (including water) or availability of heat enough to melt rocks. The rock cycle and basic geologic principles are discussed in Chapter 3. |

Fig. 1-24. The Rock Cycle is a conceptual model that portrays processes and products changing over time |

General Classification of Solid Earth MaterialsThere are 4 general classes of solid earth materials:Igneous rocks—A rock formed from molten materials, includes intrusive rocks (rocks cooled below the surface) and rocks formed on the Earth's surface by volcanism (and from melting associated with extraterrestrial impacts). Igneous rocks and volcanic activity are the focus of Chapter 7. Sediments—solid fragments of inorganic or organic material that come from the weathering of rock and soil erosion, or form from biological activity. Sediments are carried and deposited by wind, water, or ice. The processes of weathering and erosion and the focus of Chapter 8. Sedimentary rock—rock that has formed through the deposition and solidification of sediment, especially sediment transported by water (rivers, lakes, and oceans), ice ( glaciers), and wind. Sedimentary rocks are often deposited in layers, and frequently contain fossils. Sedimentary rocks are the information they reveal about ancient sedimentary environments is the focus of Chapter 9. Metamorphic rocks—Rock that was once one form of rock but has changed to another under the influence of heat, pressure, or fluids without passing through a liquid phase (melting). Metamorphism (processes that alter pre-existing rocks) and metamorphic rocks is the focus of Chapter 10. |

||||

|

AstronomyMany of the advances in modern earth sciences have come from the study of celestial objects, matter, and energy in outer space. Studies in astronomy have revealed the nature of the origin and composition of our planet. It is becoming increasingly evident that interactions of celestial objects and forces have caused mass extinctions, climate change, and other impacts in Earth's history, and will no doubt continue happening into the future. |

Earth's Place in the UniverseMany aspects of astronomy have contributed to the knowledge of the origin and geologic history of planet Earth. Meteorites have been found, collected, and studied for centuries. Telescopes on the ground and now in space, satellites, robotic and manned missions to space, the Moon, and other planets and moons in our Solar System objects have greatly expanded the collective knowledge about the origin of our planet and objects in the Solar System—all of which have evolved to their current state over billions of year. So far, life is only known to exist on Earth, but it could possibly exist elsewhere, even within our Solar System. We just haven't proven it yet.Discoveries Leading To Modern AstronomyClaudius Ptolemaeus (~100-170 CE), also know simply as Ptolemy, was an Egyptian astronomer, geographer, and mathematician (of Greek descent) who became well known in the Alexandria philosophical community in the 2nd century. Although Ptolemy made a variety of important, if not interesting, contributions to knowledge of his times, perhaps his most significant, and long lasting, was his observations of the orbits of planets and constellations. He promoted the geocentric model, that Earth was the center of the observable Universe. The ancient Greek, Roman, and Muslim astronomers followed the geocentric model (or Ptolemaic system) that described the Universe with the Earth at its center. |

Fig. 1-29. Like this giant redwood in Big Basin State Park, California. All physical materials, including life on Earth, have an origin connected to the formation of elements that formed from events that happened in space many billions of years ago! |

Early Astronomers: Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, and NewtonThe geocentric model wasn't seriously challenged until Nicolas Copernicus (1473-1543) published a report in 1543 suggesting that the Sun, not the Earth, was the center of the Universe (called Copernican heliocentrism; Copernicus provided solid scientific evidence to support Heliocentrism Theory). Nicolaus Copernicus was the first to explain the observed retrograde, looping phenomena of planet motion by replacing previously held theories of geocentrism (Earth being the center of the Universe) with heliocentrism (the Sun being the center of the Observable Universe).However, the Copernican system was also discovered to be flawed as telescopes were developed to see farther into space and astronomers began to grasp the immense scale of time and distance between our Solar System and other objects in our Milky Way Galaxy and the Universe beyond. Italian physicist and astronomer, Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) used an early telescope and discovered four large moons of Jupiter (Figure 1-30). He also promoted Copernicus's Heliocentrism Theory that the Sun, not the Earth, was the center of our Solar System. In 1615 he was subjected to the Roman Inquisition for his scientific inquiries. He was forced to publicly recant his beliefs and subjected to house arrest for the remainder of his life. (Note that the Roman Catholic Church eventually accepted his theory and officially forgave him in 1992!) |

Fig. 1-30. Galileo Galilei first used a telescope to examine the night sky. |

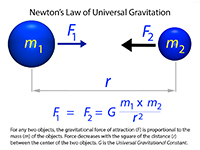

GravityGravity is a mysterious force that attracts a physical body toward the center of the Earth, or toward any other physical body toward any other body having mass (such as planets orbiting around the Sun, or moons around a planet). Gravity is a accelerating force, meaning that it's effects are similar to a measurable change in velocity. On the earth surface, the average rate of gravitational acceleration is an increase of about 9.8 meters per second per second (m/sec2).Understanding the very mysterious force of gravity is fundamental to characterizing the mechanics of the orbits of planets and moons within the Solar System (and objects moving throughout the Universe). Using research by earlier astronomers, between 1609 and 1619, Johannes Kepler presented scientific laws that describe the character of the elliptical motion of planets around the Sun. Isaac Newton used Kepler's laws to mathematically resolve the nature of gravity which he presented in 1687 as his Law of Universal Gravitation which states "a particle attracts every other particle in the universe using a force that is directly proportional to the product of their masses, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them" (Figure 1-31). Gravity is a weak but measurable force, but becomes observable when dealing with objects on the scale of moons, planets, and satellites launched into space. The force of gravity on Earth actually varies from place to place. This is due to the variations in the density of rocks preserved within the Earth's crust. For instance, rocks under the ocean basins are more dense that rocks found beneath most continental regions. Small variations in gravity are measured using a device called a gravitometer. In addition, detailed measurement in the flight paths of satellites orbiting the planet have been used to measure variations in the Earth's gravitational field. |

Fig. 1-25. Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation. All matter is subject to gravitational forces associated with other matter. Even though gravity is a very weak force, with increasing mass of an object, the force of gravity it produces also increases. Gravity is the measurable force that holds planets and moons in orbit in the Solar System. |

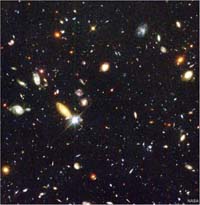

Determining the Expanse of SpaceFrom the time of Galileo to the beginning of the 20th century, the telescope technology advanced, and the night sky with it stars, planets, gas and dust clouds (nebula), and other objects were charted in great detail. The problem was that we could see lots of stars, but had no way of knowing how far away there were because stars vary in their brightness in addition to their distance. Astronomers have developed many methods to directly or indirectly measure the distance to object is space. Very large telescopes on mountain tops around the world, and many others including the Hubble Telescope orbiting Earth on a spacecraft launched in 1990, has helped to greatly expand our knowledge of the Observable Universe.It was in 1923 that Edwin Hubble found dozens of uniquely identifiable variable stars in the Andromeda nebula and then determined that Andromeda was at least 10 time more distant than the most distant stars in the Milky Way. He was first to determine that Andromeda was a separate system which he named a galaxy. The Milky Way is an obvious band of densely distributed stars and clouds of dust visible as a band in the clear night sky (Figure 1-32). Before Hubble's discovery, it was thought to be the Milky Way represented the entire Universe, and that unusual shaped spiral nebulae (galaxies) were part of the Milky Way. With Hubble's discovery, it became evident that Earth and the Sun's Solar System was within the greater Milky Way Galaxy, and that the abundance of other galaxies showed that the Observable Universe was drastically much, much larger that was previously known. |

Fig. 1-32. The Milky Way as photographed on a clear night sky. The Milky Way is the main plane of the galaxy where stars are concentrated. |

The Andromeda Galaxy is a spiral galaxy (Figure 1-33). It is the closest large galaxy to our Milky Way Galaxy and is one of the few visible to the naked eye. It is the most distant object in space that can be seen without magnification. The Andromeda Galaxy can be seen in the northern hemisphere on clear autumn nights. It is located about 2.25 million light-years away from Earth. (A light year is the astronomical distance that light can travel in a year; approximately about 9.4607 x 1012 kilometers or about 6 trillion miles.) Andromeda is estimated to contain about 1 trillion stars. Astronomers estimate that the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies will eventually collide (merge) in about 4.5 billion years in the future. |

Fig. 1-33. Andromeda Galaxy |

GalaxiesA galaxy is a system of millions to trillions of stars, together with gas and dust, held together by gravitational attraction. Deep-space observing telescopes show distant field of galaxies—galaxies and clusters of galaxies can be seen in all directions in distant space. The distance to these objects are in the range of thousands to billions of light years away from Earth. Figure 1-30 shows a field of galaxies observed in on small region in deep space. Using images like this, astronomers estimate there may be 100 billion galaxies within the Observable Universe. Galaxies appear as many shapes and sizes, but there are three general classes: spiral, elliptical, and irregular galaxies, but each of these groups are subdivided into classes (Figures 1-34 to 1-37). Small elliptical galaxies are the most common, and unlike spiral galaxies their stars do not seem to revolve around their galactic centers in an organized way. The galactic center is where the greatest mass and concentration of stars exist in a galaxy. Irregular galaxies take on many shapes, and many are interpreted as galaxies that have collided or merged under gravitational attraction. |

Earth's Place In the Observable Universe

|

Fig. 1-38. Earth's place in the Observable Universe. |

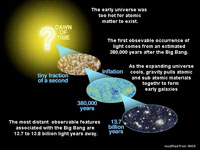

The Big Bang TheoryIn the 1927, a French astronomer, Georges Lemaître, proposed the idea that in the distant past that the Universe started as just a single point in space, and as the Universe has been expanded as a great explosion to what is observable now. Two years later in 1929, Edwin Hubble reported that the most distant observable galaxies are moving away at a faster rate than ones closer to Earth. This observation, and much other evidence, now supports a Big Bang Theory.The Big Bang Theory is a cosmological theory holding that the Observable Universe originated approximately 13.8 billion years ago from the violent explosion of a very small agglomeration of material of extremely high density and temperature (Figure 1-39). Current scientific though is that originally the material ejected from the Big Bang was too hot for subatomic particles with measurable mass to exist. It was probably many thousands of years after the Big Bang that it got cool enough for sub atomic particles and then atoms to form, and that gravitational attraction could influence the newly forming matter. Early in the history of the Universe matter began to condense and with time gravitation attraction pulled materials together to form galaxies. In 2016, the Hubble Space Telescope was able to capture an image of the furthest distant galaxy known, estimated at about 13.4 billion light years away from Earth. What is beyond the Observable Universe is unknown. See a NASA website about the Big Bang Theory. |

Fig. 1-39. A very brief story of the Big Bang and the evolution of the Observable Universe over an estimated 13.8 billion years. |

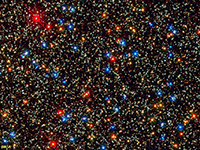

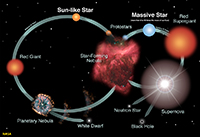

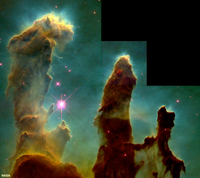

StarsA star is a self-luminous celestial body consisting of a mass of gas held together by its own gravity. Stars exist in a balance—their internal energy generated by nuclear fusion reactions results in an outflow of energy to the star's surface. This outward flow of directed gas and radiation pressures is balanced by the inward-directed gravitational forces. Since ancient times, astronomers have been charting stars into constellations—recognizable grouping of starts that appear in the night sky and move with the seasons as the Earth orbits the Sun (Figure 1-40). Although stars in constellation often appear in association by appearance, they may be large distances apart and very greatly in brightness (intensity). In addition, stars exist in a wide range of colors, most obvious when observed through telescopes or from space (Figure 1-41). Many stars are clustered together, often sharing a common stellar history (Figure 1-42). Some stars orbit each other relatively close to one another as binary systems (Figure 1-43). Some star systems have multiples stars in orbit around each other. Among the millions of stars observable in our galaxy, astronomers have been classifying them by size, color, and brightness (intensity) . Most stars in our galaxy fall into a class called the main sequence of which our Sun belongs (Figure 1-44). Astronomers have developed theories about star formation and the life cycle of stars in their different classes. With years of observation, abundance of knowledge has been gained about the life cycle of stars (Figure 1-45). Nebulae and the Formation and Life Cycle of Stars and Solar SystemsStars and solar systems form in giant interstellar clouds called nebulae. A nebula is an interstellar cloud within a galaxy consisting of gas and dust, typically glowing from radiant energy from stars nearby within them (Figures 1-46 to 1-51). Nebulae are the birth place of both stars and other objects within solar systems. Nebulae can form from the explosion of stars at the end of their life cycle, expelling gas and matter into interstellar space. Large nebula eventually begin to contract under the influence of gravity, resulting in the creation of new generations of stars and solar systems. As stars form, gravity draws material in (mostly gas) and it mass increases until the internal heat and pressure is enough to start nuclear fusion reactions (converting hydrogen into helium), igniting a new star. As stars age, they consume their fuel and eventually run out of nuclear fuel. Stars like the Sun may take billions of years to consume their nuclear fuel. When the fuel runs out, stars collapse under the weight of their own gravity. However, the fate of a star depends upon its mass. Stars up to about seven times the mass of the Sun fall within the main sequence grouping of stars. These go through stages as they consume their fuel. Young stars fuse hydrogen into helium. When stars run out of their hydrogen, the force of gravity causes them to collapse, which increases the heat and pressure within its core. During this phase of a star's life it will expand and become a red giant. Once the helium in the core of a star is consumed, stars in the main sequence will shed much of their mass into space (creating nebula), and the remaining core will shrink and cool and shrink to become a hot remnant called a white dwarf. Fate of Supergiant StarsStars with masses greater than about seven times the mass of the Sun experience a more spectacular fate. More massive stars will burn through their fuel much faster than stars of the main sequence because their cores are hotter and under greater pressure. One these massive stars burn through their hydrogen and helium, this increase in heat and pressure allows fusion to convert helium into carbon, then carbon into neon, and then into iron. As the star continues to burn through it's fuel it eventually shuts down because it the fusion process of creating iron actually consumes more energy than it produces and the star looses it balance and collapses under it own gravity. The collapsing core reaches temperatures in the range of 100 billion degree and the core recoils as a massive explosion called a nova. Great star collapses produce supernova where a star may shed the majority of it mass into space, creating a new nebulae. What happens to the core depends on the mass of the star. Stars about 7 to 20 times the mass of the Sun produce massively dense objects called neutron stars (their density is so great that electrons and protons collapse to form a great mass of neutrons). Stars with masses greater than about 20 times the mass of the Sun may collapse to form black holes. Black holes of so dense that their gravity prevents light from escaping from within their event horizons where matter is pulled into an inner space where nothing escapes. |

|

|

The Solar SystemThe Solar System is the system containing the Sun and the bodies held in its gravitational field, including the planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune), planetary moons, the asteroids, comets, and other interstellar bodies and matter (Figure 1-52).Most planets and planet systems (planets with orbiting moons) orbit the Sun in the ecliptic plane—an imaginary plain containing the Earth's and other planets' orbit around the Sun. |

Fig. 1-52. Our Solar System originated from gas, dust, and other matter that gravity pulled together in a stellar nebula about 5 billion years ago. |

|

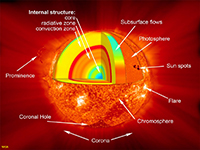

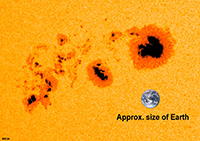

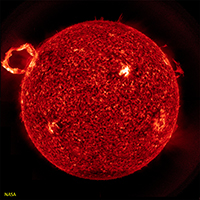

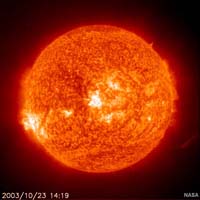

The SunThe Sun is the star at the heart of our Solar System (Figure 1-53). The sun's intense solar energy and gravity influences the planets throughout the Solar System and beyond. Facts about the Sun include:• By mass, the Sun is composed of hydrogen (70.6%) and helium (27.4%), all other elements are trace by comparison. • The Sun's average diameter is about 864,000 miles (about 109 times the size of Earth). The Sun' mass is about 333,000 times the mass of Earth. The average density of the Sun is 1.409 grams/cm3 (compared with Earth which is 5.51 grams/cm3). • The Sun rotates on its axis in an unusual way. The rotation period at the Sun's equator is about 27 days, but is about 36 days at it poles. |

Fig. 1-53. The Sun (our star), is one of billions of stars in our Milky Way Galaxy. |

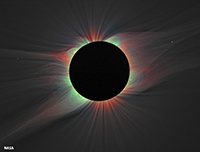

Structure of the SunThe Sun's internal structure is inferred to be subdivided into several zones (Figure 1-54).• Core—The internal temperature of the Sun's is estimated to be about 27 million degrees Fahrenheit, hot enough to drive the nuclear fusion process of converting elemental hydrogen into helium, the source of solar energy. • Radiative zone—Above the core where fusion occurs, slowly radiates upward through the massive radiative zone. • Convection zone—The temperature is estimated to drop to about 3.5 million degrees Fahrenheit, where convection of "great bubbles of dense plasma (ionized matter) rise toward the surface in a convective manner (like a pot of boiling soup). • Photosphere—A 300 mile thick layer of hot gas makes up the surface of the Sun where most of the Sun's energy radiates into space. The Sun's surface temperature is about 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit, hot enough to radiate solar energy in the visible light spectrum. • Chromosphere and Corona—The outermost layer of the Sun is a thin solar atmosphere (the chromosphere) which extends as streaming plasma deep into space (the corona). The region is not a hot as the underlying photosphere, but is heavily influence by magnetic forces generated deeper in the Sun. Features of the chromosphere are only visible with special sun-observing telescopes. However, the corona is visible during solar eclipses when the disk of the Moon's shadow temporarily blocks the intense light form the photosphere (Figure 1-55). |

|

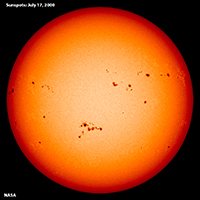

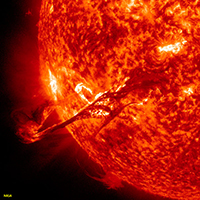

Sunspots and Coronal Mass EjectionsSunspots are relatively dark patches that appear temporarily on the Sun's photosphere (Figures 1-56 and 1-57). Sunspots are cause by a flux in magnetic fields that appear to inhibit convection. Sunspots usually occur in pairs, like the two ends of a U-shaped magnet. Sunspots last a few days to a few months before they dissipate. The concentration of sunspots on the solar surface tend to follow an 11 year cycle that also flows a small variation is the total amount of solar energy output. Coronal mass ejections are unusually large eruptions of streaming plasma and radiation (composed of charged particles) under the influence of solar magnetism. Eruptions result in the formation of solar flares and prominences (arching flares) that erupt from the Sun's surface (Figures 1-58 and 1-59). Plasma streaming from the Sun's corona results is the source of the solar wind, and coronal mass ejections in form of large solar flares and prominences can result in solar storms that can severely impact radio communications and potentially satellites orbiting Earth. |

|

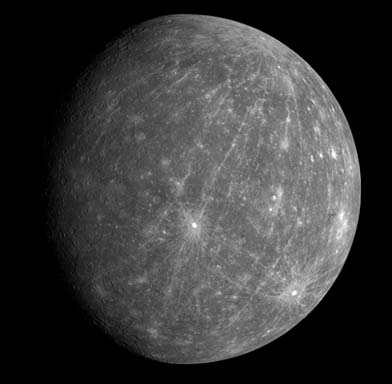

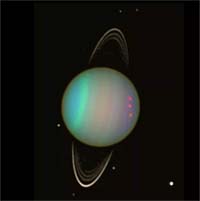

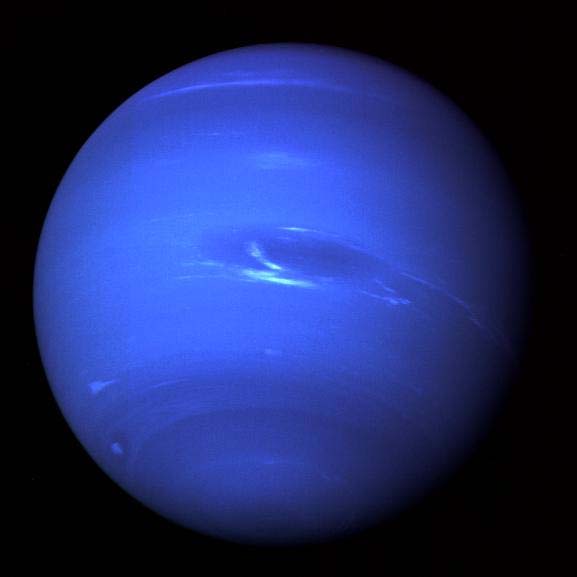

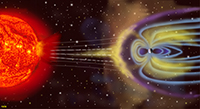

The Solar WindThe solar wind is a stream of energized, charged particles (mostly electrons and protons) flowing outward from the Sun's upper atmosphere. The ionized particles are released into space from the Sun's corona and by coronal mass ejections (prominences and flares). The solar wind moves through solar system at speeds roughly 500 miles per second (800 km/sec); about 10 days from Sun to Earth) and can reach temperatures of about 1 million degrees (Celsius). The solar wind is what blows a tail away from the bodies of comets as they go through the solar system. Estimates suggest the Sun loses the equivalent of one Earth mass about every 150 million years (which isn't much considering the size of the Sun). Large corona mass ejections from the Sun’s surface result in solar storms that frequently impact Earth and other planets.The Earth’s magnetic field shields the planet from the erosive effects of the solar wind (Figure 1-60). Particles trapped by Earth’s magnetic field flow into the upper atmosphere producing the aurora borealis (Northern Lights) and aurora australis (Southern Lights) (Figure 1-61). Over geologic time, the solar wind also erodes the atmosphere of planets with weak magnetic fields (this includes Mercury, Mars, and the Moon). Strong auroras have been observed on the gas planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune)—all of which have a dense atmosphere and a strong magnetic field. Solar storms associated with coronal mass ejections can interfere with radio communications, cause damage to satellites, and impact electrical transmission lines and facilities (resulting in power outages). During strong solar storms long lines of metal (like electrical power lines, pipelines, and railroad lines in northern regions can overload with electrical charges which and spark to nearby objects and have been reported to have started brush fires. Because massive solar ejections can be observed, the possible impacts of solar storms can be predicted. |

Fig. 1-60. Coronal mass ejections result in the solar wind which is deflected and captured by the Earth's magnetic field. Fig. 1-60. Coronal mass ejections result in the solar wind which is deflected and captured by the Earth's magnetic field. Fig. 1-61. The aurora borealis are streaming light displays in the northern hemisphere. Fig. 1-61. The aurora borealis are streaming light displays in the northern hemisphere. |

Planets and Planetary Systems of the Solar SystemA planet is a large spherical celestial body moving in an elliptical orbit around a star. A planetary system is a set of gravitationally bound celestial objects in orbit around a star or star system. Planets with orbiting moons are planetary systems. The Solar System consists of four inner rocky planets, four outer gas planets, and orbiting belts of asteroids, comets, planetesimals, and other objects under the gravitation influence of the Sun.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Earth's MoonEarth's Moon is the fifth largest of at least 168 known moons orbiting planets in the Solar System (Figure 1-70). The Moon lacks an atmosphere, and does not display any active geologic activity (such as earthquakes or volcanic eruptions). Like Earth, the Moon has a core, mantle, and a crust; geophysical data suggest the part of the Moon's core and mantle may be molten. The lack of atmosphere has helped to preserve geologic features that date back to early stages in the formation of the Solar System. |

Fig. 1-70. The Moon Fig. 1-70. The Moon moon radius: 1,079 miles (1,736 km) orbital period: 27 days average distance from Earth: 238,855 miles (383,300 km). gravity: 1.622 m/s2 |

Asteroids and CometsAn asteroid is any of the thousands of small irregularly shaped bodies of stone, metal, and ice that revolve about the sun. In our Solar System, asteroids typically range in size from about one-mile (1.6 km) to about 480 miles (775 km) in diameter (Figure 1-71). Most asteroids orbit the Sun in the Asteroid Belt located between Mars and Jupiter. However many large objects have been observed passing through Earth's orbital path. Asteroid collisions with Earth were frequent in Earth's early history, but are now extremely rare events. The extinction of the dinosaurs and many other species is mostly blamed on the environmental catastrophe created by an asteroid impact about 65 million years ago, defining the end of the Cretaceous Period (and Mesozoic Era).A comet is a celestial body thought to consist chiefly of if ices of ammonia, methane, carbon dioxide, and water, and dust (Figure 1-72). Comets are observed only in that part of its orbit that is relatively close to the sun, having a head consisting of a solid nucleus surrounded by a nebulous cloud of gas and debris (a coma) up to 2.4 million kilometers (1.5 million miles) in diameter. The coma turns into an elongated curved vapor tail arising from the coma when sufficiently close to the sun. There may be more than 100 million comets in the outer Solar System. A meteor is a bright trail or streak that appears in the sky when a meteoroid is heated to incandescence by friction with the earth's atmosphere. A meteorite is a stony or metallic mass of matter that has fallen to the Earth's surface from outer space (Figure 1-73). |

Fig. 1-71. Asteroids are solid objects in space consisting mostly of rock, dust, some metals, and possibly ice.  Fig. 1-72. Comets are like asteroids (mostly frozen gases and ice, dust, some rocky material) that leave a trail of material as they are heated as they approach the sun. |

Fig. 1-73. An iron-nickel meteorite is magnetic.  Fig. 1-74. Bolide (meteor fireball) over Oklahoma Panhandle, 9/30 2008 |

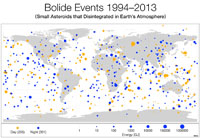

| A bolide is a large meteor (or asteroid or comet) that explodes in the atmosphere (Figures 1-74 and 1-75). About a dozen significant (recorded) bolide events happen each year. A recent bolide explosion involved the Chelyabinsk meteor that blew up over Russia on February 15, 2013. The explosion occurred high in the atmosphere, but the atmospheric shock wave blew out windows, doors, and injured over a thousand people on the ground (see YouTube video). An atrobleme is an eroded remnant of a large crater made by the impact of a comet or asteroid (large meteorite). Because of weathering and erosion processes, impact craters are relatively short lived on the Earth's surface (with exceptions for large impacts or in arid regions). Currently there are almost 200 known craters distributed on all continents. Others have been discovered by oil drilling through sedimentary cover. |

Fig. 1-75. Map of reported bolide events 1994-2013. |

| Can you explain why are there so many craters on the surface of the Moon but not on surface of the Earth? | |

The Outer Solar SystemThe region beyond to orbit of Neptune is called the Kuiper Belt. It is the circumstellar disc at the outer margin of the Solar System beyond the planets. It is similar to the Asteroid Belt, but far larger (wider) and many times more massive. The belt extends from Neptune (at about 30 AU [astronomical units] to about 50 AU - one AU is the average distance of the center of the Earth to the center of the Sun.There are more than 100,000 Kuiper Belt Objects (KBO). The Kuiper Belt includes three recognized planetesimals (or dwarf planets) including Pluto, Haumea, and Makmake. KBOs are probably mostly composed of frozen volatile compounds (ices of methane, ammonia, and water). Pluto's status as a planet has been argued for years - Figure 1-76. Pluto does not behave like other planets; it does not orbit the Sun within the ecliptic plane, and sometimes Pluto's orbit puts it closer to the sun than Neptune.) Beyond the Kuiper Belt is the hypothetical Oort Cloud - a region that may contain an abundance of icy planetesimals and objects that may surround the Solar System at a distance of between 50,00 and 200,000 AU. The Oort Cloud may be the source of most of the long-period comets that have been observed. |

Fig. 1-76. Pluto was formerly classed as a planet, but now it is called a planetesimal, or a dwarf planet in the Kuiper Belt. Pluto has 5 moons. |

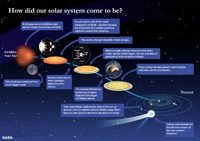

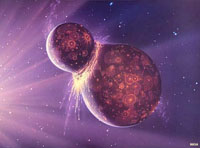

Nebular Hypothesis of the Origin of the Solar SystemMany billions of years before the formation of the Solar System there were probably several generations of star formation and destruction occurred in our region of the Milky Way. Ancient supernova explosions in the distant past produced the elements we observe in our Solar System today (an example of a fairly recent supernova explosion is shown in Figure 1-77). Nuclear fusion in stars coverts hydrogen into helium and other elements up to the atomic mass of iron. Elements heavier than iron are only created by intense energy in supernova explosions. Gas, dust, and other matter from previous supernova explosions became part of a nebula (Figures 1-78). Gravity gradually condenses material in nebulae into new star systems (see example in Figure 1-79).An ancient nebula in the Milky Way Galaxy was the birthplace of our Sun and Solar System. Currents of material (gases, dust, asteroids, etc.) under the influence of gravity consolidated into the proto suns and proto planets of new star systems within the nebula, one of which became our Sun and Solar System. Because all matter is influenced by gravity, matter within nebulae gradually is pulled toward areas with more matter. As matter moves toward a location with greater density it may be caught in a spinning current around a center of accumulating matter that may become a sun or a planet. • The combination of gravity and spin results in the formation of a flat, disk-shaped stellar cloud with the Proto Sun (or pre Sun) at the center. The increasing mass and gravity of the Sun grabs most of the matter in the evolving Solar System (Figure 1-80). • The Sun eventually gains enough mass that nuclear fusion can begin, creating the intense energy that it radiates into space. • The massive release of energy from the new Sun heats the surrounding stellar region, combined with the force of high energy plasma (the solar wind) pushes the light elements (mostly hydrogen and helium) out of the inner Solar System region. As a result: • Inner planets form from the accumulation mostly of metallic and rocky substances (dust). Lighter gas materials are pushed to the outer regions of the Solar System. • Larger planets in the outer part of the Solar System began forming from gases (mostly hydrogen) and fragments of ice (H2O, CO2, and other gases). • The Sun and its Solar System gradually formed by the gravitational attraction of materials within a stellar nebula beginning almost 5 billion years ago. • The evolving Solar System assumes a flat, disk shape of condensing gases and dust with the Proto Sun (or pre Sun) at the center. The consolidation of matter under gravitational attraction causes the surrounding nebular cloud to flatten and spin. • After solar ignition (initiation of the Sun's internal nuclear fusion reactions), the Sun's intense solar energy and solar wind begins to drive gases away from the inner Solar System. • Inner planets begin to form from metallic and rocky substances (dust). • Larger outer planets began forming from fragments of ice (H2O, CO2, and others). Proto-Earth FormedStudies of meteorites and samples from the Moon suggest that the Sun and our Solar System (including proto-planets) condensed and formed in a nebula before or about 4.56 billion years ago. A recent Scientific American article places the current assumed age of the Earth is about 4.56 billion years old. Currently, the oldest samples of Early Earth rock samples from the Jack Hills region of Australia that contain crystals of the mineral zircon dated to an age of about 4.4 billion years.Earth also formed through gravitational attraction of interstellar dust, gases, small asteroids and larger objects (planetesimals) within the early Solar System consolidating within the Sun's stellar nebula and within its orbital belt around the Sun. • Initially, the Earth was probably homogeneous in composition, eventually becoming extremely hot and mostly molten within. • Proto-Earth was probably under constant bombardment by asteroids, comets, and planetary dusts and debris. • Current thought is that the Proto-Earth grew larger in size than today’s Earth. Formation of the Earth-Moon SystemProto-Earth experienced a great planetary collision resulting in formation of the Moon.Studies of the rocks brought back from the Apollo Missions show that the Earth and Moon have similar mineral and isotopic compositions. Such an impact probably vaporized much of the upper portion of the Proto-Earth, throwing much of it into space. Gravity eventually consolidated the material into the Earth-Moon system. This, and the fact that the Earth has a tilted axis, and the Moon's orbit is not in the ecliptic plane, suggest that the Moon may have formed from the collision of another small planet-sized object with the Earth early in the history of the Solar System (Figure 1-81). It is this tilt to Earth's axis that gives rise to the seasons as it orbits the Sun. The Moon's surface displays a heavily cratered surface, many of the craters are massive in scale. Dark-colored maria are regions on the lunar surface where molten material flooded the surface, filling in depressions created by massive impacts. The lighter-colored highland regions on the Moon are rugged mountainous regions consisting of heavily cratered moonscapes and tectonic features that formed early in the Moon's history when the mantle was more molten and lighter material floated to the surface to crystallize and form the lunar crust. The cratering was a result of asteroids and comets collisions, mostly within the first billion years of the Moon's history. |

Fig. 1-77. Supernovas are great explosions that partial to complete demolish aging stars, releasing new matter and gas to create a new generation of stars.  Fig. 1-78. Nebula, the birthplace of stars; some are formed from the explosion of other more ancient stars, some thousands to millions time larger than the Sun.  Fig. 1-79. Pillars of Creation, a part of Eagle Nebula in our Milky Way Galaxy where new stars are forming and emerging from a gas and dust cloud—a stellar nursery.  Fig. 1-80. A brief explanation of how the Solar System came to be through the process of stellar evolution.  Fig. 1-81. Proto Earth colliding with another object |

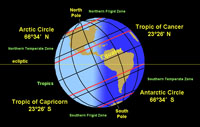

Zones of the Earth Climate System and SeasonsOn any location on the planet, the slow progress of seasonal changes are related to observable migration that the path the Sun follows through the sky over the cycle of one year. Seasons occur because:• the Earth spins (rotates) on its axis marked by the north and south poles; and, • the axis of the spinning Earth is tilted about 23.5° relative to ecliptic plane. The ecliptic plain is flat circular path the Earth and other planets follow as they revolve around the Sun in the orbital plane)(Figures 1-82). Seasons occur because of the tilt in Earth's axis as it revolves around the Sun (Figure 1-83). Only twice a year, on the spring and fall equinoxes the Sun is directly above the equator (0°). The summer solstice occurs on June 21 when the Sun is directly overhead at noon along the latitude 23.5° north (a circle on the globe called the Tropic of Cancer). Likewise, the winter solstice occurs on December 20 when the is directly overhead at noon along the latitude 23.5° south (a circle on the globe called the Tropic of Capricorn). The tropics are the region of the world between the parallels of latitude between 23.5° north (Tropic of Cancer) and 23.5° south (Tropic of Capricorn) on opposite sides of the equator (0°). The term polar is used to describe the high latitude cold regions surrounding the Earth's north and south poles. The Arctic Circle runs 66.33° north of the equator. North of this line is the North Frigid Zone (also known as The Land of the Midnight Sun where the Sun never sets on the summer solstice). The Antarctic Circle is parallel of latitude approximately 66.33° south and defines the northern boundary of the South Frigid Zone. The Antarctic Circle marks the approximate limit south of which the Sun remains above the horizon all day on the summer solstice. The regions between the tropics and the polar regions are called temperate zones (North Temperate Zone and South Temperate Zone). |

Fig. 1-82. The location of tropics, temperate, and polar zones is related to the Earth's tilt on its axis.  Fig. 1-83. Seasons are caused by the tilt in Earth's axis as it orbits around the Sum. |

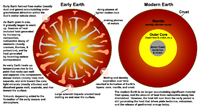

Evolution of Earth’s Layered StructureEarth has a layered structure, having an outer rocky crust and mantle overlying a molten and solid metal core, however, this internal layered arrangement did not exist early in Earth's history (Figure 1-84).• Early in Earth's history the composition of the planet was probably more homogeneous. However, just like oil and water don't mix, metals separated from non-metal substances, and as metals are denser, gravitation forced them to sink toward the planet's core. • Likewise, molten material rich in dissolved gases and lighter silica-rich matter is less dense and over time it gradually migrated upward accumulating in the mantle and thin crust where some of it reached the surface, resulting in volcanism and massive degassing. • Despite intense asteroid bombardment, early crust began to form. • Chemical segregation under the influence of gravity established the basic divisions of Earth’s interior (core, mantle, and crust). This process also happened with other planets, moons, and planetesimals in the Solar System. The structure of the Earth is discussed in detail in Chapters 3 and 4. |

Fig. 1-84. Formation of the early Earth and the eventual development of its internal layered structure: core, mantle, and crust. Volcanic degassing and accumulating gases from space led to the formation of Earth's atmosphere and oceans. |

|

Origin of Earth's Atmosphere and OceansThe study of meteorites and material in space suggest the early Earth probably had large quantities of water, organic compounds, and other gases trapped in the accumulating material forming the planet. As a result, as rocks melted large amounts of volcanic outgassing took place. This volcanic outgassing contributed to the atmosphere forming around the planet. Volcanic outgassing from the Earth's interior is still taking place as illustrated by gas emissions from volcanic eruptions such as those on Hawaii or on Iceland where the source of molten material is known to be rising to the surface from the mantle (Figure 1-85).• Current thought is tat large volumes of water vapor and carbon dioxide formed Earth's primitive atmosphere. The atmosphere was also rich in nitrogen, methane, and ammonia. • Early in Earth history the Earth probably had a thick, hot atmosphere. The surface of the planet was probably hotter than the boiling point of water, so much of the planet's water was trapped as water vapor in the atmosphere. • Early on, no continents or oceans probably existed (at least no trace of them are preserved from that time), and no evidence of life on Proto-Earth has been discovered. • Eventually the surface cooled enough for early crust to began to form. With a solid crust and reduced surface temperatures, rainfall could begin to accumulate in depression on the surface. As more and more water was released from the atmosphere oceans began to form. • By about 4 billion years ago (BYA) the Earth's oceans were essentially in place. Oldest rocks from Canada are of this age. • Nearly 2 billion years ago, life had advance enough for photosynthesis to take place, gradually consuming the vast reservoirs of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and dissolved in the oceans, while releasing oxygen to accumulate in the atmosphere (discussed in Chapter 16). |

Fig. 1-85. Volcanic outgassing of the interior of the planet is still taking place, as illustrated by volcanic eruptions on Hawaii. |

|

Water and Oceans On Other Planets and Moons |

|||

| Water is known to exist throughout the Solar System and beyond. However, liquid water is only known on the surface of planet Earth where surface temperatures and atmospheric pressures are in the range where it can remain fluid. Tidal forces between planets and their moons provide a source of energy to keep water in liquid form below the surface of some of the moons in the Solar System. |

|||

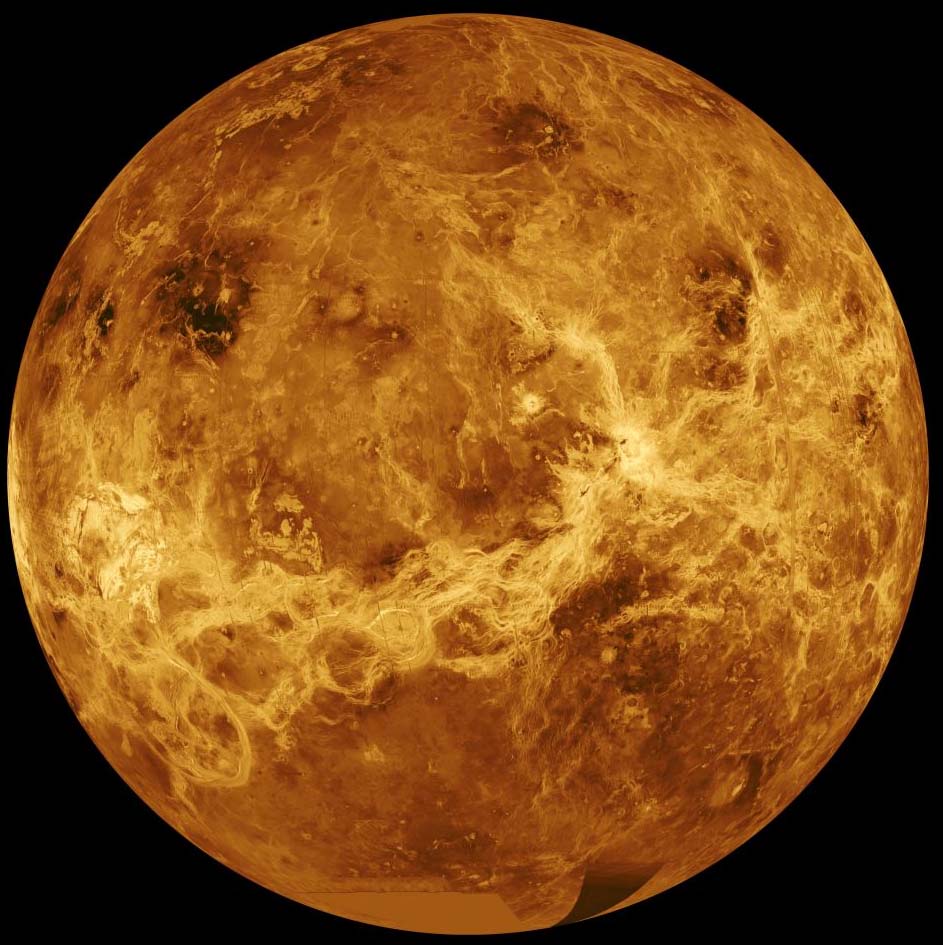

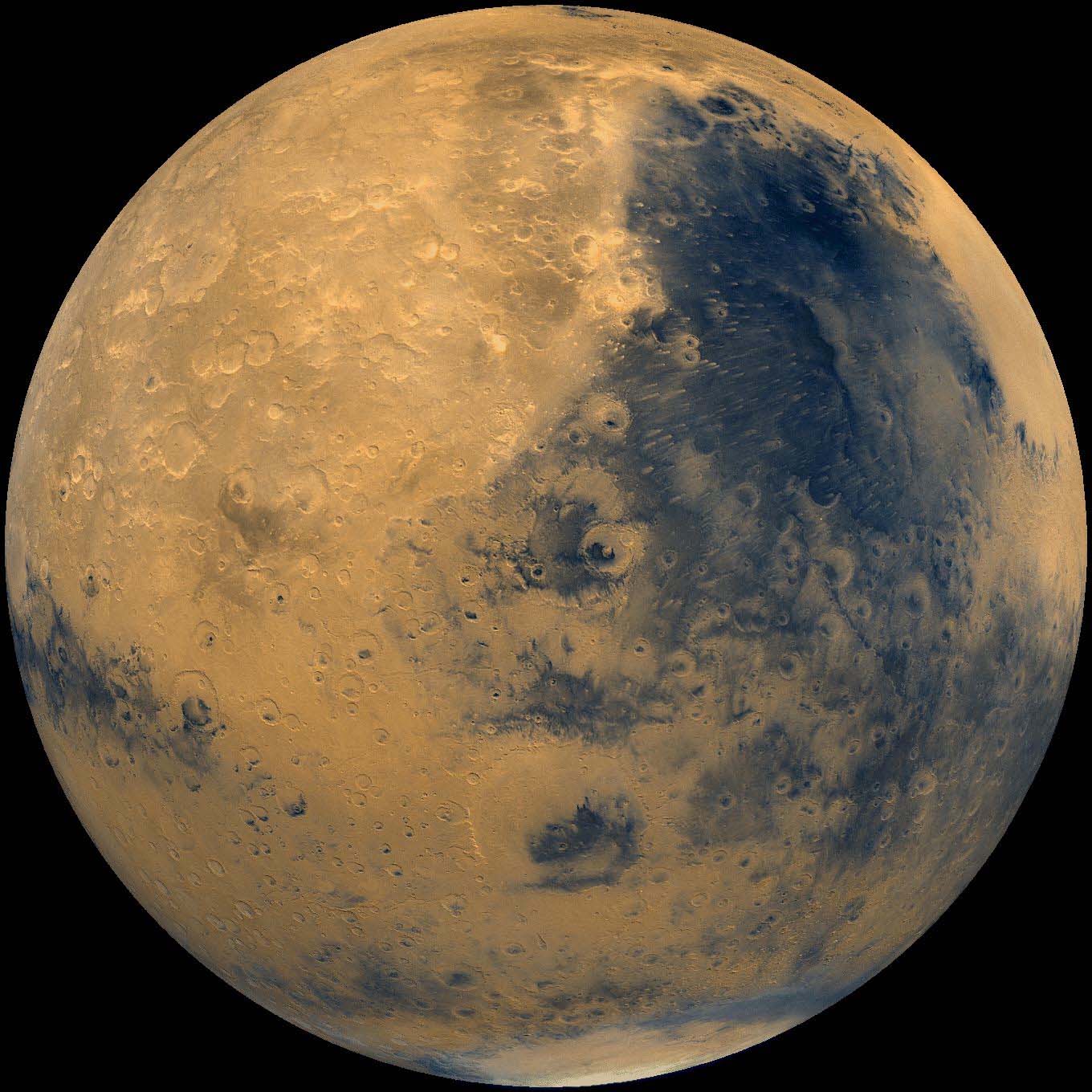

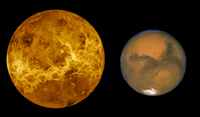

| Both Venus and Mars likely had liquid water oceans early in the evolution of the Solar System, but now Venus is too hot for water to exist, and Mars is too cold and its atmosphere is too thin. Exploration of Mars suggests that liquid water may exist underground and traces may locally flow on the surface, causing erosion, where conditions are right (Figures 1-86). |

|||

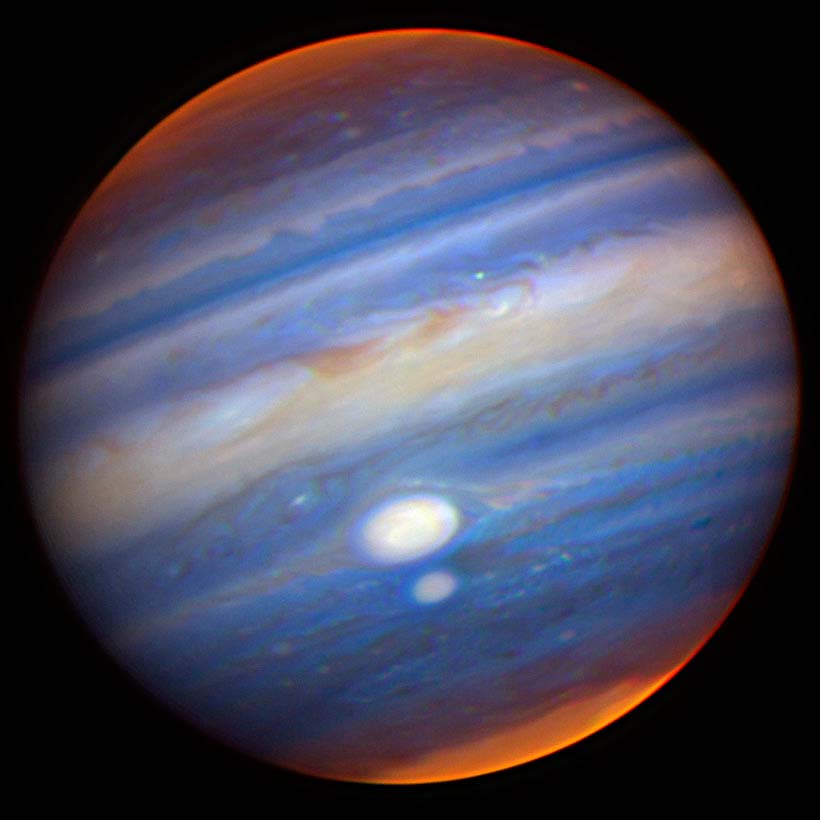

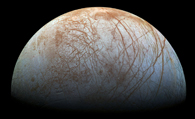

| Europa: Exploration of the Jupiter planetary system suggest that its moon, Europa has an outer crust of solid ice about 10–30 km (6–19 mi) thick which overlies a liquid ocean thought to be about 100 km (60 mi) deep (Figure 1-87). The volume of water in this subterranean ocean is estimated to be more than two times the volume of Earth's oceans! |

|||

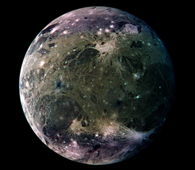

| Ganymede: A subsurface saline ocean is also theorized to exist on Jupiter’s moon Ganymede. Its ocean is estimated to be 100 km deep and lies beneath a crust of ice estimated to be about 150 km thick (Figure 1-88). |

|||

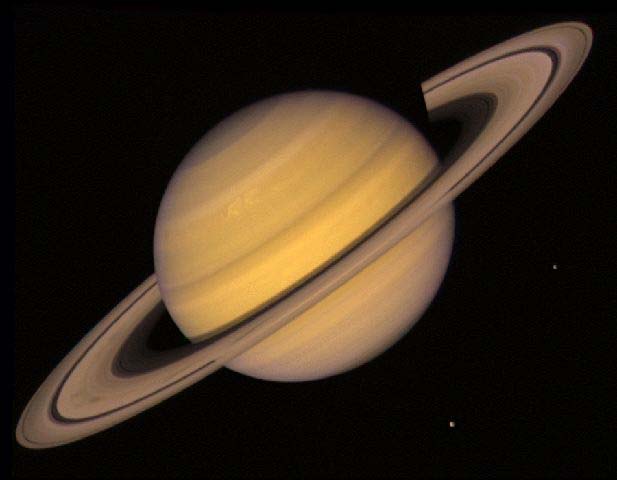

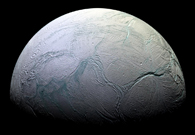

| Enceladus: Saturn’s moon, Enceladus, is also believed to have a subsurface ocean and NASA’s Cassini spacecraft observed geysers of water erupting from Saturn’s moon, Enceladus during its exploration of the planet system. Spectrographic observations of the geysers also contained traces of salt, carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and hydrocarbons. The moon also has liquid water oceans below its surface, and the geysers appear to be driven by tidal forces between the moon and Saturn (Figure 1-89). |

|||

| Water planets outside the Solar System: In recent years, astronomers working with powerful telescopes have been finding planets orbiting other stars within our "galactic neighborhood." Although most of these planets are larger than our Earth, some of the planets display evidence of water, possibly oceans. | |||

| Fig. 1-86. Venus and Mars | Fig. 1-87. Europa | Fig. 1-88. Ganymede | Fig. 1-89. Enceladus |

Name of Full Moons of the YearSupermoon is the term given when a full moon occurs at the same time as perigee − when the Moon is closest to Earth as its closest point as it revolves in its elliptical orbit around the planet.Blood Moon is when the moon takes on a red color as it passes through a lunar eclipse. Even though the Moon is dark as it passes into the shadow of the Earth, light filtering through the Earth's atmosphere is refracted and directed toward the Moon, giving it a slight red glow. Most of the shorter wavelengths of light (blue and green) are absorbed or dispersed as it passes through the atmosphere, so only the red light gives the Blood Moon its color. Note that the Moon revolves around the Earth at a tilted angle of about 5 degrees off the ecliptic plane (the plane that most planets orbit around the Sun). Because of this tilt, lunar eclipses only occur when the path of the Moon crosses the ecliptic plane during a full-moon phase. |

Names Full Moons In Different Months and SeasonsWolf Moon is the first full moon that occurs after the Winter Solstice (typically in January). Other names for this moon is the Old Moon or Moon after Yule. The Wolf Moon is named for the midwinter moon when packs of wolves howled hungrily outside of Indian villages. |

| Snow Moon occurs in February and gets its name because the heaviest snows typically fall this time a year. For some Indian tribes it is also called the Hunger Moon because of the lack of supply of food in the heart of winter. |

| Worm Moon is the first full moon of spring (after the Spring Equinox). Other nicknames for this full moon is the Sap Moon, Sugar Moon, Crow Moon and Crust Moon. |

| Pink Moon is named for the pink blooms of pink phlox flowers that bloom all over North America in mid to late April. Other nicknames includes Sprouting Grass Moon, Fish Moon, Egg Moon. |

| Flower Moon is associated with the blooming of May flowers. It is also called the Milk Moon and Corn Planting Moon. |

| Strawberry Moon is associated with the full moon in June near the Summer Solstice. It gets it name for the ripe berry fruit typical of late spring/early summer. The full moon in June is also called the Mead Moon. |

| Buck Moon is the full moon of July and is named after the regrowth of elk and deer antlers. July's moons are also called the Thunder Moon, Hay Moon, Rose Moon. |

| Sturgeon Moon is the full moon of August. It is also called the Green Corn Moon. |

| Harvest Moon is the full moon of September or October, whatever full moon falls closest to the Fall Equinox. It is also called the Corn Moon, Barley Moon, or Fruit Moon. |

| Hunters Moon is the name for the full moon of October (when it occurs after the Harvest Moon). |

| Beaver Moon occur in November. It is also called the Snow Moon and is named as a reminder of the coming winter cold. |

| Cold Moon is the December full moon (when it occurs before the Winter Solstice). It is also called the Oak Moon or Moon before Yule. |