Woodson Mountain (elevation 2,881 feet) is a major landmark in coastal San Diego County (shown near the center of the banner view above, looking west from the Del Dios Highlands near Escondido). The mountain peak rises nearly 2000 feet above nearby highland valleys and mesas in the Poway and Rancho Bernardo areas (Figure 1).

Figure 2 is a topographic map that shows the trail system around Woodson Mountain, Lake Poway, and the Blue Sky Ecological Reserve and Lake Ramona. The Mt. Woodson Trail is one of the most popular hiking trails in San Diego County. The trail begins at the Lake Poway Staging Area. The hike to the Mt. Woodson Summit is involves a 2,000 foot climb in elevation. This 8 mile round trip hike takes about 3-4 hours and is only recommended for experienced hikers capable of a strenuous workout.

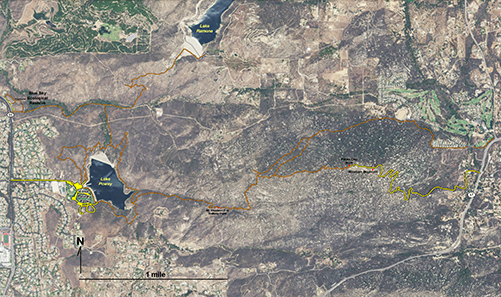

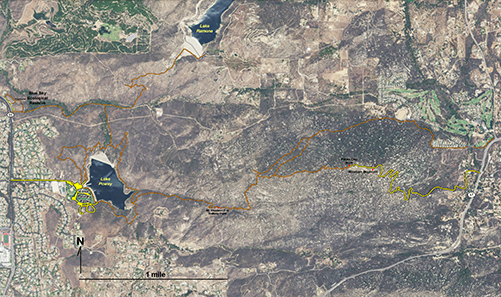

Figure 3 is a satellite map of the Woodson Mountain area. The steep slopes of the mountainside are covered with chaparral vegetation surrounding an abundance of large granite boulder outcrops (appearing as speckled dots on the satellite image).

|

Click on images for a larger view. |

Fig. 1.Woodson Mountain.

|

Fig. 2. Topographic map of the Woodson Mountain area. |

Fig. 3. Satellite map of the Woodson Mountain area. |

A1

Geologic Setting of Woodson Mountain

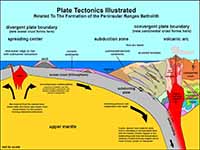

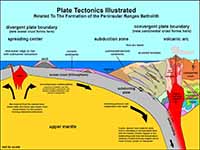

Woodson Mountain is a monadnock — an isolated hill or ridge or erosion-resistant rock rising above a peneplain. The story of the origin of Woodson Mountain began more than 100 million years ago when a volcanic arc was active along the western margin of the North American continent. Bodies of magma were rising from sources deep in a subduction zone. As the molten rock approached the surface, some erupted as volcanoes, whereas much of it cooled and crystallized deep below the surface. Over time, numerous large igneous intrusions (plutons) accumulated to form the Peninsular Ranges Batholith (Figure 4). The bedrock beneath Woodson Mountain is part of one of the massive plutons of granite within the batholith that extends all along the core of the Peninsular Ranges. The Peninsular Ranges Batholith extends northward from Baja California into southern California near Los Angeles. When it was forming back in the Mesozoic Era it was part of same chain of volcanoes (volcanic arc) that formed the Sierra Nevada Batholith throughout central and northern California. |

Fig. 4. Plate tectonic model showing origin of Peninsular Ranges Batholith.

|

100 Million Years Of Landscape Evolution

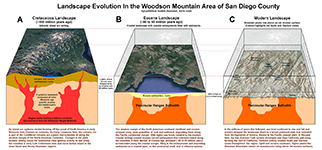

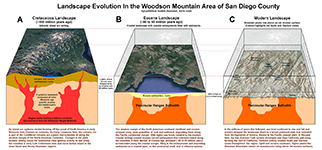

In Late Cretaceous time the geometry of the plate-tectonics setting along the North American continental margin changed. At the peak of igneous activity in Cretaceous time, large volcanoes must have lined up along the continental margin similar to the volcanic arcs similar to those we see in the Cascade Range or Aleutian Islands (Figure 5A). Subduction ended along the coastline in Late Cretaceous time and gradually moved much farther inland to the Great Basin and Rocky Mountain regions. Without the supply of magma to feed a coastal volcanic landscape, erosion began to dominate. For nearly 50 million years gradual erosion stripped away thousands of feet of rock, removing the volcanoes and exposing the their "roots" in the plutonic crystalline rocks of Peninsular Ranges Batholith (Figure 5B).

By Eocene time (50 to 45 million years ago), the land had eroded down to a low peneplain, A peneplain is a a nearly level land surface produced by erosion over a long period, undisturbed by crustal movement. This old erosion surface sloped very gently from the highlands of northern Mexico to the Pacific coastline. Gradual erosion continued on into mid-Tertiary time, creating a landscape with broad valleys between lowland hills and the eroded remnants of what were once much larger mountains. Rivers draining from the highlands of Mexico dropped large quantities of gravel, sand, and sediments along the coastline, resulting in accumulations that are preserved in the Eocene rock formation we see in the coastline today (such as at Torrey Pines State Nature Reserve). Coastal erosion from persistent wave action slowly carved the shoreline landward creating embayments between areas of more erosionally-resistant bedrock that became headlands or islands regions along the coastline. These Eocene-age deposit probably once surrounded the Mount Woodson area but they have long since been stripped away, exposing the highly fractured granite bedrock exposed in the area today (Figure 5C).

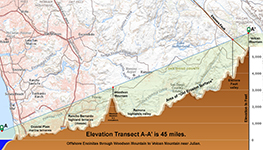

By mid-Oligocene time (about 30 million years ago), the plate tectonic setting changed again as the San Andreas Fault system began to develop. Over time, a massive crustal block split away from Mexico, forming Baja California. This block of crust that contained the the Peninsular Ranges Batholith begin its is gradual migration northward attached to the Pacific Plate. Over time, the eroded peneplain on the surface of the Peninsular Ranges Batholith began to slowly rise (forming the modern Peninsular Ranges). The physiographic region know as the Area of the "Old Erosion Surface" is part of a large coherent piece of crust called the Santa Ana tectonic block (Figure 6). However, sea level continued to rise and fall over time, and coastal erosion carved embayments along the coastline. These embayments later became coastal plains, and eventually the mesas in the Area of High Terraces (Miocene to Pliocene age) and the younger Area of Coastal Plain Terraces (Quaternary age).

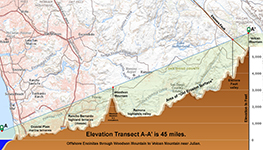

Figure 7 is an elevation profile transect (A-A') that extents for offshore of Encinitas for 45 miles to the peak of Vulcan Mountain, a high peak along the crest of the Peninsular Ranges near Julian, CA. The profile shows the character of the Old Erosion Surface on the stable Santa Ana tectonic block, west of the Elsinore Fault Zone. Woodson Peak stands out as a monadnock along the boundary between the the highlands valley of the Ramona area and the Area of High Terraces (now mesas) in the Escondido, Rancho Bernardo, and Poway areas (as shown on Figure 6). |

Fig. 5. Landscape evolution of the Woodson Mountain area of San Diego County in A) Cretaceous time, B) Eocene time, and C) the modern landscape (with faults/fracture zones). |

Fig. 6. Physiographic regions of San Diego County reflect dynamics changes in the regional landscape over time. |

Fig. 7.

Elevation profile transect between offshore Encinitas, Woodson Mountain, and Volcan Mountain illustrates the physiographic regions. |

|

Landscape Views of the Woodson Mountain Area

The images presented below illustrate the scenic view hikers can experience on a hike the Mt. Woodson Trail to the summit area of Woodson Mountain where the famous (or potentially notorious) Potato Chip Rock is located. |

Fig. 8. Looking across Lake Poway with the Mt. Woodson Trail ascending the boulder and chaparral covered slopes. |

Fig. 9. View looking north at Lake Poway from near the trailhead for the Mt. Woodson Trail. |

Fig. 10. View Looking back from the Mt. Woodson Trail toward Lake Poway Park on the shore of the lake. |

Fig. 11. View looking toward the northwest toward the coastal mountain with landscape features labeled. |

|

Spheroidally Rounded Boulder And Outcrops

In many mountainous areas in San Diego County, the landscape displays an abundance of large, rounded granite boulders and outcrops. Woodson Mountain is covered with many large, rounded boulders and outcrops that rise above the surrounding chaparral, the local dominant plant community (Figures 12 to 14). The boulders are easy to see on the satellite image (Figure 3). It is also easy to see the abundant fractures that cross the mountainsides and through the area around the park. Some are major fracture zone, possibly fault zones. Many of the stream drainages follow fracture or fault lines that cross the granite bedrock on the mountainside. Some of the fractures probably formed long ago when the batholith was forming. Others formed later as the modern fault system developed across the region, probably the same time period as when the the San Andreas Fault system formed, splitting Baja California away from Mexico. However, there are no known earthquake faults in the vicinity of Woodson Mountain (that is, there are no faults known to be capable of producing large, damaging earthquakes).

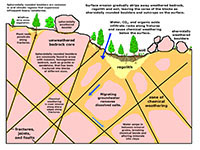

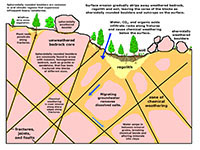

Figure 15 illustrates the origin of spheroidally rounded boulders and outcrops. Their origin is related to two factors: the bedrock consists of heavily fractured granite, and the climate is ideal for their formation. The long dry summers and infrequent rainstorms in the winter and summer monsoon season allow for wetting and drying periods. Water, gazes, and organic acids seep into fracture, chemically weathering the rocks along the fracture zones and, over time, expanding the zone of weathering inward toward the central cores of bedrock blocks below the surface. Plant grow on the surface contributes to the weather process by expanding root systems in the fracture zones and contributing organic acids that help break down the chemical bonds that cement mineral grains together. Episodic wildfires burn through the chaparral, exposing the loose soil and regolith to intense erosion during infrequent heavy rains. Over time, the rounded core of bedrock blocks are exposed and accumulate on the surface. |

Fig. 12. Large boulders and outcrops of the flank of Woodson Mountain. |

Fig. 13. Boulder-covered slope on Woodson Mountain with Black Mountain to the west. |

Fig. 14. View looking north past a boulder toward Lake Ramona. |

Fig. 15. Diagram showing the origin of spheroidally rounded outcrops and boulders. |

|

Woodson Mountain Summit and Potato Chip Rock

Most people who attempt the 4 mile, one-way hike to the summit of Woodson Mountain are usually on a journey to visit Potato Chip Rock near the summit of Woodson Mountain (Figure 16). The summit area is actually off limits because it is host to a very large array of antennas (Figure 17). Warning signs discourage people from going near the antenna array for unforeseen risks of exposure to radiation used for radio and microwave data transmissions.

On any typical spring or fall weekend day a long line can form for people wanting to take their turn, sometimes waiting hours, to get their picture taken standing, or behaving in some manner, on Potato Chip Rock (Figures 18 and 19). From a geologist's perspective, it is definitely a death-defying act to climb out on a thin slab of brittle granite that juts out about 80 feet above the rocky mountainside below. You need to consider that the "potato chip" formed when a massive portion of the spheroidally rounded outcrop split away and tumbled down the slope below. It is not uncommon to see groups of people gather on the ledge, and some people actually jump up and down on it. This is definitely not recommended. Some day it will break... Crunch! Rocks, even mountains, and certainly "potato chips" don't last forever. |

Fig. 16. Sign near Potato Chip Rock showing distances to the Woodson Mountain summit and Lake Poway Park. |

Fig. 17. View looking up the trail to the summit of Woodson Mountain covered with large boulder and antennas. |

Fig. 18. People waiting in line to get onto Potato Chip Rock for a "death defying" experience... (?) |

Fig. 19. Performers performing a performance on Potato Chip Rock.

|

|

| City of Poway, Lake Poway Park (official city website with trail descriptions). |

| https://gotbooks.miracosta.edu/fieldtrips/woodson_mountain/index.html |

5/6/2021 |

|