Blue Sky Ecological Reserve |

|

A1

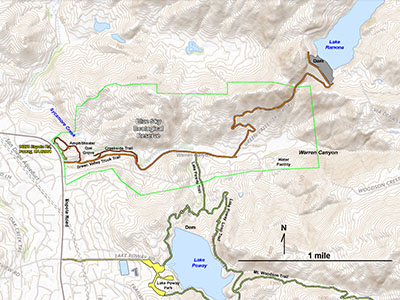

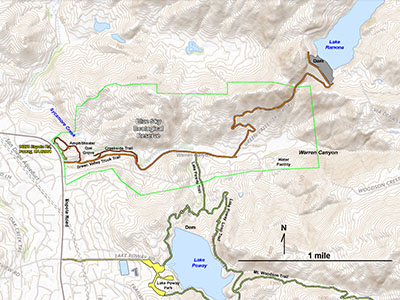

The Blue Sky Ecological Reserve encompasses 700-acres in Warren Canyon on the north side of Woodson Mountain and Lake Poway Park. The reserve is a conservation area for a variety of flora and fauna supported by the City of Poway and the California - Department of Fish and Game (Figure 1). Well maintained hiking trails provide access to oak woodlands and riparian habitats along Sycamore Creek, and slopes covered with coastal sage scrub and chaparral plant communities that can be seen along trails that lead up to Lake Ramona and Lake Poway (dams and reservoirs). Figure 2 shows trails and landscape features on a topographic map. Figure 3 is the same area shown on a satellite image. Also see the Woodson Mountain field guide.

A parking area for the Blue Sky Ecological Reserve is located at 16275 Espola Road, Poway, CA 92064. Access to the trails in the reserve and to Lake Ramona is also from the Lake Poway Park. Docents working for the reserve offer hands-on experiences to identify and observe plants and animals, and conduct resource preservation activities, and programs. Reserve hours are sunrise to sunset daily. See details at Blue Sky Ecological Reserve, Information Brochure (Poway.org).

|

Click on images for a larger view. |

Fig. 1. Blue Sky Eoclogical Reserve.

|

A2

Landscape Features

The reserve is located along the linear valley of Warren Canyon drained by Sycamore Creek. The linear nature of the canyon hints that the canyon was carved along an ancient fault or fracture zone in the granitic bedrock of the Peninsular Ranges batholith that underlies the region (discussed below). Lake Poway and Lake Ramona reservoirs were constructed in adjacent highland valleys that drained into Warren Canyon. |

Fig. 2. Topographic map of the Blue Sky Ecological Reserve area showing trails. |

Fig. 3. Satellite map of the Blue Sky Ecological Reserve area An abundance of granite outcrops are scattered on the slopes. |

A3

Blue Sky Ecological Reserve Trailhead Area

The image gallery below illustrates many of the features in the Blue Sky Ecological Reserve and along the trails that connects the reserve to Lake Poway Park to Lake Ramona. The Green Valley Truck Trail is the main in the reserve that starts at the parking area on Espola Road (Figure 4).

The Torretto Overlook Trail starts near a kiosk in the parking area. It is a short loop trail that leads past an amphitheater used for outdoor education programs and special events (Figure 5 and 6). Beyond the amphitheater the trail leads to an overlook area that provides scenic views of the forested valley along Sycamore Creek in Warren Canyon (Figures 7 and 8). The massive, granite boulder-covered slopes of Woodson Mountain are visible along the south side of Warren Canyon (Figure 9). The Torretto Overlook Trail connects to the Green Valley Truck Trail not far from the trailhead (Figures 10 and 11).

The Green Valley Truck Trail (GVTT) trailhead is just south of the parking area on Espola Road (Figure 10), The first 1.2 miles is a relatively flat trail that follows along the forested floodplain of the Sycamore Creek (Figure 11). At 0.2 miles the GVTT intersects the Creekside and Oak Grove Trails (see below). At 0.9 miles the GVTT connects with the Lake Poway Trail, and 1.2 miles from the trailhead, the GVTT makes a left turn and begins an uphill ascent of about 700 feet to the top of Lake Ramona Dam. |

Fig. 4. Information Kiosk in the Blue Sky Ecological Reserve parking area. |

Fig. 5. Torretto Overlook Trail and leads past an outdoor amphitheater. |

Fig. 6. Outdoor amphitheater for the Blue Sky Ecological Reserve. |

Fig. 7. Granite boulder along the Torretto Overlook Trail overlooking Sycamore Creek. |

Fig. 8. View looking east along Warren Canyon in the Blue Sky Ecological Reserve. |

Fig. 9. Zoom view of Woodson Mountain from the Torretto Overlook Trail. |

Fig. 10. Trailhead for the Green Valley Truck Trail just south of the parking area. |

Fig. 11. View along the Green Valley Truck Trail (now a pedestrian-only trail). |

|

A4

Oak Grove Trail and Creekside Trail

At 0.2 miles, a narrow path leads off the Green Valley Truck Trail to the left into the forest along the trail. It comes to a T-intersection. To the left is the short Oak Grove Trail, to the right is the Creekside Trail.

The Oak Grove Trail only goes a few hundred feet into a cluster of large, old Coast Live Oak trees growing on the floodplain along the creek bed (Figures 12 to 14). The forest setting is very scenic with nice shade on a sunny day. It is important to stay on the trail, not only because of the sensitive nature of the habitat, but also because there is abundant poison oak along the trail (Figure 15). "Leaves of three, let it be!" Note that poison oak looses its leaves in the winter, but the barren branches can retain their toxic oils that can cause severe rashes.

The Creekside Trail winds through the riparian habitat along Sycamore Creek for about a quarter mile before returning to the GVTT (Figures 16 to 19). Along this shaded path there are more oak trees, sycamores, willows, toyon, laurel sumac, chamise, white sage, monkeyflowers, and a myriad of other low-growing flowering plants and shrubs. Signs and displays along the trails are provided to help identify plants and their communities. |

Fig. 12. Large Coast Live Oak trees along the Oak Grove Trail along Sycamore Creek. |

Fig. 13. Large Coast Live Oak tree along the Oak Grove Trail along Sycamore Creek. |

Fig. 14. Large Coast Live Oak trees along the Oak Grove Trail along Sycamore Creek. |

Fig. 15. Poison oak occurs in abundance along the Oak Grove and Creekside Trails. |

Fig. 16. Sensitive habitat - keep out sign along Sycamore Creek. |

Fig. 17. Riparian habitat along the Creekside Trail along Sycamore Creek. |

Fig. 18. Granite boulder on a natural pedestal along the Creekside Trail. |

Fig. 19. Oak woodlands and coastal sage scrub habitats along the Creekside Trail. |

|

A5

Green Valley Truck Trail To Lake Ramona

At 0.9 miles from the trailhead, the Green Valley Truck Trail (GVTT) intersects the Lake Poway Trail. At the intersection there are a couple picnic tables in the shade of a large oak (Figure 20). The Lake Poway Trail leads uphill for 0.5 miles and connects with, the Lake Poway Loop Trail below the Lake Poway Dam (Figure 21). Continuing on, the Green Valley Truck Trail passes through more open country with patches of mixed oak forest and coastal sage scrub plant communities (Figure 22). At 1.2 miles, the trail intersects a service road that lead to a water storage/pumping facility. At that intersection, the trail turns to the left and begins its ascent up the mountainside to Lake Ramona Dam (Figures 23 and 24). The trail leaves the forest and trees behind and the views become more expansive the higher you go.

Figure 25 show the east end of Warren Canyon. This straight canyon that leads up to a divide and probably formed along the trace of a fault or fracture zone. Note how the north-facing slope of the canyon is covered with chaparral whereas the south-facing slope is mostly rocky and barren of vegetation.

Figures 26 and 27 show the water storage/pumping facility and and a pipeline running up and over the flank of Woodson Mountain. The low rumble of the plant can be heard throughout the upper valley area.

Figures 28 to 34 show views at the GVTT climbs higher onto the mountain as it approaches Lake Ramona Dam. Figure 30 shows Lake Poway Dam on the opposite side of Warren Canyon. Figures 31 and 32 show a large, rounded granite boulder precariously perched above the paved section of the trail leading to the dam.

Figures 33 to 37 show the setting of the granite-block covered Lake Ramona Dam and the reservoir flooding Highland Valley. Highland Valley is another linear canyon that erosion carved along another ancient fault of fracture zone.

Figure 38 is a zoom view showing the radio tower array on the top of Woodson Mountain. Figure 39 is a zoom view looking down at the distant Lake Poway (dam and reservoir).

|

Fig. 20. Picnic tables at the intersection 0.9 mile from trailhead, 1.5 miles to Lake Ramona, 0.5 to Lake Poway. |

Fig. 21. The Lake Poway Trail leads a half mile along a forested canyon up to the base of Lake Poway Dam. |

Fig. 22. Coastal sage scrub and oak woodland plant communities along the Green Valley Truck Trail. |

Fig. 23. Sign saying 1.2 miles to Lake Ramona near the intersection with the road to the waterworks facility. |

Fig. 24. The Green Valley Truck Trail leaves the forest and starts uphill to the dam. |

Fig. 25. Warren Canyon is a linear valley that likely follows a fault or fracture zone. |

Fig. 26. Woodson Mountain as seen from the north side of Warren Canyon along the trail. |

Fig. 27. The Warren Canyon water pumping facility and pipeline on Mt. Woodson. |

Fig. 28. Laural sumac (bush) and dodder (orange parasitic plant) along trail. |

Fig. 29. View looking up the Green Valley Truck Trail below Lake Ramona Dam. |

Fig. 30. View down the Green Valley Truck Trail with Lake Poway Dam in the distance. |

Fig. 31. Boulder looming over the Truck Trail road below Lake Ramona Dam. |

Fig. 32. Large boulder looming over the Truck Trail below Lake Ramona Dam. |

Fig. 33. View looking down the canyon below Lake Ramona Dam. |

Fig. 34. Lake Ramona Dam view from the Green Valley Truck Trail. |

Fig. 35. View looking at the back of Lake Ramona Dam from the east end of the dam. |

Fig. 36. View of Lake Ramona from the east end of the dam.

|

Fig. 37. View of Lake Ramona from the middle of Lake Ramona Dam. |

Fig. 38. Zoom view of Lake Poway dam and reservoir as seen from Lake Ramona Dam. |

Fig. 39. Zoom view of the summit of Woodson Mountain from Lake Ramona Dam. |

|

A6

Dam Facts

Lake Ramona (dam and reservoir) was constructed in the remote Highland Valley in the early 1980s. It was built by the Ramona Municipal Water District as a storage facility to provide a dependable and uninterrupted future source of water. The earthen dam is 228 feet high. The elevation at the top of the dam is 1,360 ft. The reservoir covers 556 acres, and has a capacity to hold as much as 12,000 acre-feet of water. Only shoreline fishing is allowed at Lake Ramona in designated areas and a State of California fishing license is required.

Lake Poway (dam and reservoir) is owned by the City of Poway and was constructed between 1970 and 1972 with the purpose of storing and supplying water, and providing recreational facilities to the community. The earthen dam is 165 feet high. The elevation of the top of the dam is 935 feet. The reservoir has a surface area of 35 acres, and a capacity of 3,800 acre-feet of water. Both limited boating and fishing are allowed on Lake Poway. |

A7

Geology of the Blue Sky/Lake Ramona Area

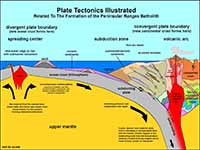

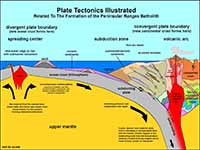

The bedrock in the Blue Sky Ecological Reserve and around Lake Ramona consists mostly of granitic rocks common throughout the Peninsular Ranges batholith region. These rocks formed from the cooling and crystallization of magma in massive plutons that formed along a subduction zone that existed along the western margin of the North American continental plate in Early Cretaceous time, about 100 million years ago (Figure 40). These plutons formed deep underground, but were gradually uplifted and eventually exposed by erosion stripping away the land's surface over the 100 million years that followed their formation.

Figure 41 shows a slope along the Green Valley Truck Trail covered with outcrops and boulders typical of granite that formed in the ancient plutons. Figures 42 and 43 show close-up views of the coarse-to-medium grained granite (more technically, an igneous rock named tonalite) that is composed of interlocking crystal grains of quartz, plagioclase feldspar, and dark minerals including biotite, magnetite, and amphibole. Some outcrops of the granite contain dark inclusions of basalt or fragments of metamorphic rock (Figure 44). These rocks were derived from the roof or sidewalls of the ancient magma chamber, or were carried upward from sources deep below as the molten material migrated into the magma chamber.

Along the GVTT there are several locations where the original host rock are exposed (Figures 45 to 47). These rock are older than the igneous intrusions;. These are parts of large blocks that rock from the side or roof of the magma chamber that survived complete melting. They consist of a rock called migmatite, a complex rock of both metamorphic and igneous origin. The blue-gray rock is schist that had been fracture and intruded by small, light-colored igneous dikes consisting of quartz and feldspar. The schist bears resemblance to outcrops of the Julian Schist, a formation prebatholithic metasedimentary wall rocks preserved along the margins of the Peninsular Ranges batholith in central and eastern San Diego County. These metasedimentary rocks originally formed from ancient ocean basin sediments that accumulated along the margin of the continent in early Mesozoic time (Triassic and Jurassic time). |

Fig. 40. Plate tectonics model showing the origin of the Peninsular Ranges batholith. |

Fig. 41. Granite outcrops cover the south-facing slope along Warren Canyon. |

Fig. 42. Coarse crystalline granite (tonalite) in outcrop near Lake Ramona Dam. |

Fig. 43. White granite (tonalite) in boulder on Lake Ramona Dam. |

Fig. 44. A basalt inclusion embedded in a granite outcrop near Lake Ramona Dam. |

Fig. 45. Migmatite, blue schist with veins of light-colored minerals (quartz and feldspar). |

Fig. 46. Migmatite, blue schist with mineral veins with large crystals of quartz and feldspar. |

Fig. 47. Migmatite with dikes offset by small faults exposed in the GVTT road bed. |

|

A8

Weathering and Erosion Processes Shaping The Landscape

Features in the bedrock shows that tectonic forces have uplifted of the landscape. Granite that formed deep below the surface, and metasedimentary rock that originally formed deep below the seafloor are now exposed high on the flanks of the mountains. We can also see an abundance fractures and faults scattered throughout the bedrock. These indicate that over the many millions of years the rocks have been shattered probably by thousands of strong earthquakes.

What goes up, must come down. As the land has slowly risen, the forces of weathering and erosion are stripping away the surface of the landscape. Weathering involves both the physical and mechanical breakdown of rocks, converting them into sediments. Erosion involves processes that move rock material and sediments downslope under the influence of gravity by flowing water or ice, landsliding, or wind-blown fine-grained sediment ("dust" composed mostly of silt, and clay).

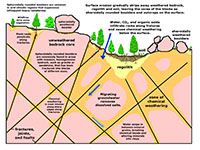

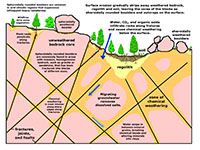

The breakdown of bedrock actually begins below the surface (Figure 48). Earthquakes mechanically fracture the rocks. Also, rocks that were once buried deeply below the surface expand and crack as they release their confining pressure. These fractures (including fault zones) become pathways for water to seep into the ground. Fractures also become locations for plant roots to penetrate and expand, assisting in the mechanical breakdown of the bedrock. Over time, the combination of groundwater, gases, and organic acids contribute to the gradual penetration and dissolution of minerals, breaking the bonds that hold mineral grains together. In rocks like granite, this weathering process works its way from the outside inward. Chemical weathering starts along the shattered, jagged edges of blocks of rocks first and slowly working into toward the unweathered core. These processes can be easily seen in the fresh cuts along roads, such as along the Green Valley Truck Trail (Figures 49 and 50). The alteration of iron-bearing minerals into limonite (FeO(OH)·nH2O, which is basically rust) gives the weathered rock and soil its brownish color.

In some areas the deeply weathered granite becomes a layer of unconsolidated rocky material covering the bedrock (called regolith, Figure 51). With the introduction of organic material (plant debris, microbial matter, and remains of organisms) regolith is converted to soil. However, on the mountainsides in arid regions climate plays a major role in shaping the landscape. In most coastal mountain areas, wildfires rage across the landscape, typically a couple times a century (more or less). Flames remove the plant cover, bakes the organic residues out of the thin soil cover, and even scorches the surface of exposed rocks. Fire season (during the summer season) is followed by periods intense rainfall during late summer monsoon thunderstorms or winter rainstorms. heavy rainfall washes away the loose sediment on the surface. Over many years, these cyclic events gradually wear down the landscape, leaving behind boulders and unweathered bedrock exposed in patches across the landscape (as illustrated in Figure 41 and on the slopes of Woodson Mountain).

|

Fig. 48. Diagram showing the origin of spheroidally rounded outcrops and boulders in a fractured granite bedrock. |

Fig. 49. A fresh road cut is a place to see weathering processes occurring along fractures in the granite. |

Fig. 50. Spheroidal weathering can be seen in the outcrop of deeply weathered granite exposed in a road cut. |

Fig. 51. Deeply weathered granite crumbles easily, and easily washes away during infrequent rainstorms. |

|

A9

Poway Clasts (Ancient River Cobbles)

Another interesting story about the evolution of the regional landscape is the origin of the Poway clasts. Poway clasts are stream-rounded cobbles composed of durable volcanic rock of rhyolite and andesite porphyry composition. They are typically pinkish, reddish, to purple in color, and display speckles of light colored feldspar crystals. These clasts can be found scattered in spots on the landscape and exposed in the dirt along the trails (Figure 52). In places they have been moved and piled along the Green Valley Truck Trail (Figure 53). Their appearance, composition, and origin have given them their unique identity.

In Eocene time (about 50 to 45 million years ago), an ancient river system drained out of the volcanic highlands of Sonora, Mexico. The ancient Ballena River sorted and deposited gravel on ancient floodplains and dumped large quantities of gravel-rich sediment into the ocean along the ancient continental margin. Deposits of the ancient Ballena River are preserved in the Poway area (how they got their name). Massive deposits of these ancient river gravels (now conglomerate) are exposed along the south wall of Poway Valley (on Poway Mesa) in locations south of Woodson Mountain and near San Vicente Reservoir. In that area, the ancient river river floodplain gravel deposits are spread out along a discontinuous east-west band about 16 mile long and as much as 2 miles wide. These massive beds of conglomerate have been assigned to the Poway Group, subdivided of 3 rock formation with an estimated total thickness of about 1,000 feet (Elias, 1919; and Kennedy and Moore, 1971).

The ancient Ballena River system existed long before the plate-tectonic changes occurred that lead to the formation of the San Andreas Fault system and the gradual opening of the Gulf of California that began roughly 30 million years ago. Poway clasts can be seen in ancient submarine channel deposits exposed in the seacliffs north of La Jolla. In many places the Poway clasts have been reworked over and over. They can be found scattered on the surfaces of the ancient highland stream terraces, in caprocks on the region's mesas, and on the coastal marine terrace throughout the San Diego region. |

Fig. 52. A Poway cobble exposed in the Green Valley Truck Trail.

Fig. 53. Poway river gravel clasts removed in construction along the trail.

|

A10

Selected ResourcesCity of Poway, Parks & Recreation, Trails & Hiking. This website provides interactive maps and a Poway Trails Guide and Map (.pdf). City of Poway, Lake Poway Park (official city website).

Ellis, A.J., 1919, Geology, IN Ellis, A.J., and Lee, C.H., Geology and ground waters of the western part of San Diego County, California: U.S. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper, 446, p. 50-76.

Kennedy, M.P., and Moore, G.W., 1971, Stratigraphic relations of Upper Cretaceous and Eocene formations, San Diego coastal area, California: American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, v. 55, no. 5, p. 709-722.

|

Fig. 54. "Keep of the rocks" sign at Lake Ramona Dam. |

| https://gotbooks.miracosta.edu/fieldtrips/Blue_Sky/index.html |

5/12/2021 |

|