Regional Geology of North America |

|

Northern Great Plains |

Click on images for a

larger view. |

The Northern Great Plains include North and South Dakota, and eastern Montana and Wyoming (Figure 93). Most of the eastern and northern portions of the region experienced glaciation, and the landscape consists mostly of low rolling hill country typical of surficial glacial moraine and till deposits. Interstate 90 crosses southern South Dakota into Northern Wyoming. Between Sioux City and Chamberlain, I-90 cuts through croplands on the glaciated till plain. Chamberlain, SD overlooks the "Breaks of the Missouri"—the incised canyon of the Missouri River. Landslide-prone slopes exposed the Pierre Shale of Late Cretaceous age (Figure 94). The Pierre Shale underlies most of South Dakota and represents sediments deposited in the Late Cretaceous Seaway. The elevation of the Missouri River crossing at Chamberlain is 1,354 feet. To the west of Chamberlain, the land steadily rises to Wall, SD (2,825 feet). South of Wall is Badlands National Park, famous for its fossiliferous exposures of the White River Group—a group of rock formations that range in age from Eocene to Miocene age (Figure 95). The White River Group preserve evidence of the character of the after the withdrawal of the Western Interior Seaway—coastal lowlands, to upland forests, to high western desert prairie climates. The name "badlands" refers to the impression of the eroding landscape held by early settlers heading west. Badlands National Park was also established as a preserve for American Bison (commonly called buffalo) that were nearly wiped to extinction in the late 19th century (Figure 96).

|

|

|

|

|

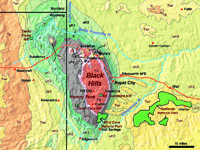

| Fig. 93. Northern Great Plains - South Dakota, North Dakota, eastern Montana and Wyoming. /td>

| Fig. 94. Breaks of the Missouri, hill country along the Missouri River in Chamberlain, South Dakota. |

Fig. 95. Tertiary sedimentary rocks of the White River Group erode into badlands in Badlands National Park, South Dakota. |

Fig. 96. American Bison in grazing on short-grass prairie in Badlands National Park, South Dakota. |

|

The Black Hills

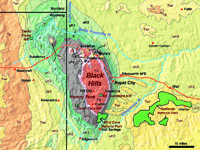

West of Wall, South Dakota, Interstate 90 descends through the Breaks of the Cheyenne River where Pierre Shale is also well exposed. At Rapid City, SD (elevation 3,202 feet), I-90 skirts around the north side of the Black Hills Uplift before it crosses into the high rolling plains of the Powder River Basin of eastern Wyoming. The Black Hills are an outlier of the Rocky Mountains, a massive mountainous dome that rose above the Western Interior Seaway starting about 70 million years ago (Figure 97). Over millions of years, erosion has stripped away thousands of feet of sediments, exposing ancient rocks in the core of the Black Hills. The core's bedrock is composed of both metamorphic and plutonic igneous rocks ranging 1-8 to 2.8 2 billion years. Harney Peak (elevation 7,244) is the highest peak in the Black Hills, it is composed of Precambrian-age granite (Figure 98). Mount Rushmore National Monument is carved into the granitic core rocks (Figure 99).

The sedimentary rock formations of Paleozoic and Mesozoic age crop out on the flanks of the uplifted core. Large cavern systems have formed in the rising Black Hills Uplift including those in Wind Cave National Park, Jewel Cave National Monument, and many others occur in Mississippian-age marine limestones in the outcrop belt around the core. During the Triassic and Jurassic Periods, the Black Hills region was lowlands that occasionally was flooded by shallow seas. Paleozoic rocks are overlain by Triassic red-beds, Jurassic layers consist of limestone, sandstone and shale. Lowlands surrounding the black hills consist of Late Cretaceous marine shales deposited in the Western Interior Seaway. Laramide Orogeny is the name of the mountain-building period when the large ranges in the Wyoming and Colorado Rocky Mountain ranges were uplifted. Initially shallow inland seas flooded the basin between rising mountain ranges. Over time, the rising Laramide mountain ranges flooded the surrounding regions, filling the basins with sediments. In the Powder River Basin and around the Black Hills these sediments are preserved as the White River Group (Eocene to Miocene time), best known for exposures in Badlands National Park.

Laramide volcanism: Scattered around the northern Black Hills are a about a dozen igneous intrusion structures that formed in early Tertiary time during the peak of the Laramide Orogeny. Devils Tower National Monument is named for the famous natural landmark in northeastern Wyoming (Figure 100). Devils Tower is the eroded remnant of what may have been a laccolith (an intrusive body trapped between sedimentary layers) or possibly the stock of a volcano (however, any trace of a what many have been volcano have eroded away).

|

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 97. Geologic map of the Black Hills region, South Dakota and Wyoming. |

Fig. 98. Harney Peak, the high point in granitic core of the Black Hills of South Dakota. |

Fig. 99. Mount Rushmore National Monument in the Black Hills of South Dakota. |

Fig. 100. Devils Tower NM, Wyoming is the erosional remnant of a volcanic stock. |

|

Great Plains of North Dakota and Eastern Montana

Interstate 94 crosses the Northern Great Plains between Fargo North Dakota to Billings, Montana, (see Figure 93). East of Fargo, the landscape is is covered with forests and many small lakes. West of Fargo, the forest transitions to prairie grasslands and agricultural croplands. Between Fargo and Bismarck, North Dakota, the interstate crosses glaciated-till plains. West of Bismarck (on the Missouri River), the climate grows dryer and crop farming transitions to range land and dry-land farming. Along the western side of North Dakota, the Little Missouri River has carved a canyon with badlands exposing sediments of the Cannonball Formation of Paleocene age. Theodore Roosevelt National Park is a American Bison preserve in the heart of the Little Missouri River badlands region (Figure 101).

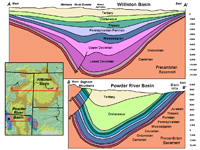

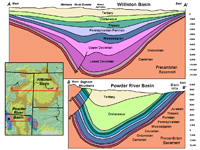

The Paleocene-age Cannonball Formation was deposited in the Cannonball Sea, a remnant of the once greater Western Interior Seaway. The outcrop belt of the Cannonball Formation roughly outlines the extent of the Williston Basin, a large structural basin that approaches 12,000 feet thick at its center (Figure 102). The Williston Basin began to form in middle Paleozoic time. Late Paleozoic-age formations grow increasing thicker toward the center of the Basin. The Williston Basin is currently experiencing a oil and gas drilling boom utilizing fracking technologies.

The region around Miles, Montana is famous for dinosaur hunting. The Hell Creek Formation of Late Cretaceous age was deposited on the coastal plain of the Western Interior Seaway. Fossils of dinosaurs Tyrannosaurus rex, Triceratops, and many others have been mined from this region (Figure 103).

The Montana city of Great Falls takes its name from a series of 5 waterfalls along the upper Missouri River. It is famous for the arduous task of portage around the falls by the Lewis and Clark expedition (1805-6)(Figure 104).

|

|

|

| Fig. 101. Theodore Roosevelt National Park encompasses the Little Missouri River in the Williston Basin region of North Dakota. |

Fig. 102. Geologic cross sections of the Williston Basin (Montana and North Dakota), and the Bighorn Basin (northeast Wyoming). |

|

|

| Fig. 103. Hell Creek badlands near Miles, Montana is a target of many dinosaur-hunting expeditions. |

Fig. 104. Great Falls on the Missouri River in Montana is famous for the famous portage of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. |

| https://gotbooks.miracosta.edu/geology/regions/northern_great_plains.html 1/20/2017 |

|

|

|

|