Hudson River Valley Region

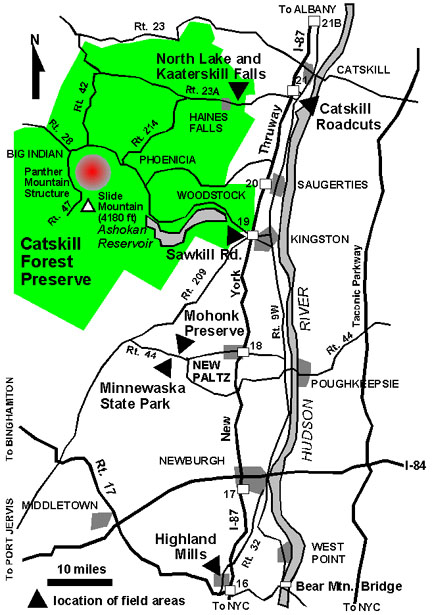

The Hudson River flows southward from headwater areas in the Adirondacks region to Troy, New York, where it approaches sea level and becomes an estuary (becoming brackish and under the influence of tides). The Hudson River flows southward through the northern extension of the Great Valley, a lowlands region underlain mostly by Lower and Middle Paleozoic shales and carbonate rocks, with a surficial cover of Quaternary glacial and alluvial deposits. Just south of Newburgh, New York, the Hudson River crosses into the crystalline rocks of Highlands Province. The rocks beneath the Great Valley are gently to steeply dipping sedimentary rocks that locally display northward-trending faults, evidence of tectonism associated with the Taconic and Acadian Orogenies. Outcrops along the New York Thruway (1-87) provide many tantalizing views of folded Paleozoic formation which, unfortunately like all interstate road cuts, are off limits for casual examination. Even along lesser highways in the region sites that have been host to field study in the past are now posted to keep people away. However, with a collection of maps, articles, and guidebooks (many are listed in the references section), it is still possible to find ample places to safely study the geology. Figure 55 is a map of the central Hudson Valley region.

|

| Figure 55. Map of the Catskill Mountains and central Hudson River Valley region. |

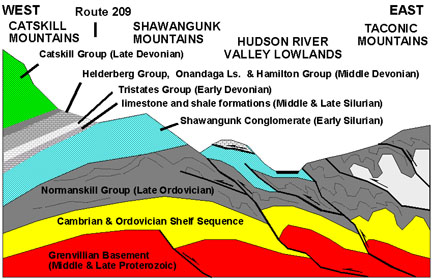

A generalized east-to-west cross section across the Hudson River Valley in the Kingston serves to illustrate the character of the regions geology (Figure 56). To the east the Hudson River the land steadily rises to the highlands of the Taconic Mountains, a region noted for its great décollements (allochthonous masses of rock associated with great thrusts faults formed during the Taconic Orogeny, and later reactivated during the Acadian Orogeny). The lowlands in the Hudson Valley region between Newburgh and Kingston are underlain by folded clastic rocks, mostly shale, of Ordovician age (Normanskill and Austin Glen Formations). Along the western side of the Great Valley are escarpments created by resistant, gently dipping Silurian and Devonian strata. To the south and west of Kingston, the Shawangunk Conglomerate appears and gradually increases in to approaching 1,700 feet, its maximum thickness, in the Swawangunk Mountains west of New Paltz. This ridge-forming unit continues southwestward into New Jersey where it forms the ridge crest of Kittatinny Mountain along the western margin of the Great Valley. Above the conglomerate, the stratigraphic succession of younger Silurian and Devonian strata is dominated by shale, limestone, and dolomite formed from sediments deposited in migrating depositional environments associated with a shallow inland seaway. Route 209 between Kingston and Port Jervis follows the general trend of a valley where this belt of strata crops out. It dips gently to steeply to the northwest, creation a saddle between the escarpments of the more resistant, coarser clastic Silurian strata and the younger coarser clastic strata of the Late Devonian Catskill Group. (A "group" includes two or more stratigraphic formations with significant features in common.) In between are the variable stratigraphic sequences of the Early Devonian Helderberg Group, and the Middle Devonian Tristates and Hamilton Groups (see Figure 54). The massive limestones within the Helderberg Group are responsible for the scenic high cliffs of the Heldeberg Escarpment in James Boyd Thatcher State Park (about a dozen miles west of Albany).

|

| Figure 56. Generalized east-to-west cross section through the central Hudson Valley region. |

The Catskill Group represents a great accumulation of clastic sedimentary material along the western margin of the Acadian Highlands, the ancient upland region that encompassed most of New England as a result of regional uplift during the Acadian Orogeny. From the Hudson River Valley region the Catskill sequence grows progressively thicker to the west to its maximum thickness of over 7,000 feet along the Pennsylvania border. South and west of the Scranton, Pennsylvania area the Catskill sequences grows progressively thinner. During the Late Paleozoic the sequence was possibly more than twice its current thickness, and the deposits probably extended far north and east into portions of New England. This overburden has subsequently been removed by erosion.

| Return to Valley and Ridge Province Main Page. |