75. The Westhampton Beach Disaster

Westhampton Beach in the late 20th Century provided a classic example of how difficult it is to manage a barrier island. Well-intended interests to preserve and protect expensive beach front property and homes ultimately resulted in a major disaster for barrier island residents down shore. Whereas many of the local owners in the disaster area suffered significant financial losses, most of the initial repair costs were paid by tax payers (both state and federal). The Westhampton Beach disaster is an interesting example of how shore communities must deal with the risks and issues associated with long-term barrier island management. The long term gamble for communities like South Hampton and Westhampton will be whether local and regional tax support from the coastal communities will cover ongoing shoreline management expenses, including the expenses of disasters caused by unexpected storms.

With the on-going rise in sea level and the constant progress of beach erosion, most Atlantic beaches are currently retreating shoreward at an average rate of between one and three feet per year (although in many places new land is also forming from accumulation of previously eroded material). This crude estimate is based on the record of changes on maps and aerial photos of the coastline. As illustrated by Sandy Hook, Breezy Point, and Fire Island, shores reflect the buildup of the spits by longshore drift at the expense of the up-current beach. At Westhampton Beach, one of the most obvious indications that the beach is migrating landward is the abundance of swamp peat washing up on the ocean front beach (Figure 198). This material is eroding from older bay side deposits that are now being eroded by wave energy from locations offshore from the ocean beach.

|

| Figure 198. Clam-bored peat eroded from submerged deposits offshore from Westhampton Beach. One indication that the barrier islands are migrating shoreward. |

The loss of beach was noted by the people of the threatened town of Westhampton Beach, but instead of condemning the beach front homes they appealed to politicians for assistance. After many political and legal battles, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built a total of 15 groins from 1966 to 1970 on the west side of the barrier island, however, the project ran out of money leaving the eastern communities along the western end of the Westhampton Beach barrier island unprotected. The project was supposed to have been financed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, New York State, and the local community. With the latter two sources quickly running out of funds, the plan was never completed to specifications (i.e., the town was supposed to have contributed funds for beach sand replenishment down current to protect the barrier island's west end). The town of Southampton failed on its promise to add sand to the beaches west of the "last" groin, citing its own financial difficulties. Also, the design of the 15 existing groins was flawed. They were too long, sticking out farther into the surf than was necessary, and they were too closely spaced. As a result, the beach in the groin field became "over nourished." by the buildup of sand provided by longshore drift. Sand quickly filled in the new accommodation space in the groin field. The homes in this area certainly became well protected, or even over protected, as the natural buildup of dunes invaded their back yards and diminished their oceanfront views.

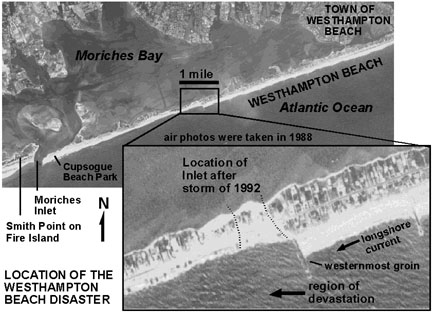

The opposite was true at the western, down-current end of the groin field. The curtailment of the sand flux from longshore drift resulted in intensified erosion to the community of Westhampton Beach (Figure 199). As soon as the groins were built, 20 feet of the down-current beach eroded. The natural beach dune that protected the communities to the west of the dune field began to steadily disappear. Soon after, waves generated by a series of minor storm began to lap at the back doors of homes. Starting with several severe nor'easters in the late 1970s homes began to vanish, and the lawsuits began to accumulate with fingers pointing in all directions. Through the 1980s more homes continued to be destroyed, but nothing significant was done to correct the problem.

|

| Figure 199. Aerial photographs of the disaster area at Westhampton Beach. |

Then came the nor'easter of November, 1992. This severe storm provided gale- and hurricane- force winds with accompanying exaggerated-amplitude waves and storm surges at high tide. Worse, the storm lasted nearly four days. During this storm the barrier island was breached just beyond of the westernmost groin (down-current) built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. This created an new inlet that quickly grew progressively wider to about a quarter mile. The land where 80 houses once stood was now under water. In addition, many of the surviving housed were heavily damaged, and all of those that remained on the western end of the barrier became isolated on the new island. The new inlet had cut through the only access road.

With all of the media attention of the disaster, the government finally responded by offering emergency relief funds. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers commenced a series repair operations. Their first move involved filling in the breach zone with the sand that spilled into the bay side of the new inlet. They pumped sand back onto the beach and used a bulldozer to push up "artificial dunes." (Experience shows that artificial dunes are never as effective at preventing erosion as the much more well-consolidated natural dunes.) They also raised the level of the center of the island above an estimated storm surge level, and began an operation to shorten the two westernmost groins, using these materials to build a shorter one just down-current from where the inlet had formed (Figure 200).

|

| Figure 200. An operation to modify the groins at Westhampton Beach in 1997. |

While building more groins may have saved the community now known as Westhampton Dunes, the cost of the project and the politics involved prevented their construction. The first lawsuits were filed 1966, and were still in progress in the late 1990s. The cumulative cost of this disaster in 1998 was in the vicinity of $50,000,000, most of which was paid for by the State of New York. In return, the community on the barrier island was forced to allow, and provide limited parking for, public access to their one-time relatively private beach. Perhaps most perplexing to tax-payers and coastal geologists is that the home owners were allowed to return and rebuild property in the exact locations that nature had previously destroyed. No attempt was made to reconcile the fact that sea level is still rising, the shoreline is naturally migrating, and the natural up-current sand supply is steadily becoming depleted. However, the disaster had its benefits (albeit temporarily)... the shellfish production in the bay actually increased with the new supply of plankton-rich marine water provided by the temporary inlet, and reconstruction brought jobs.

Only the future will tell how much more taxpayers will be willing to pay to support shore development (and disaster repair). The lessons learned from the Westhampton Beach disaster can apply to practically any coastal community, anywhere. As food for though, below is a summary of costs of selected shore modification and disaster repair on Long Island.

"Top 10" most expensive known New York beach "disaster repair" or modification projects:

$30,700,000 in 1996 ($47,168,000 adjusted since 1962) - Westhampton Beach

$11,183,000 in 1994 ($64,472,000 adjusted since 1960) - Gilgo Beach

$9,420,556 in 1975 ($135,705,000 adjusted between 1926 to present) - Rockaway

Beach

$9,000,000 in 1995 ($26,708,000 since 1923) - Coney Island

$3,771,000 in 1994 ($9,892,000 between 1990-1996) - Hempstead Beach

$1,940,000 in 1990 (+$200,000,000 adjusted since before 1959) - Jones

Beach

$1,650,000 in 1993 - Tiana Beach

$1,329,000 in 1992 - Plumb Beach

$844,100 in 1962 ($5,047,000 adjusted) - Great South Beach

$528,600 in 1962 ($3,161,000 adjusted) - Brookhaven & Islip area

(Source: New York Beach Nourishment Summary [retrieved in 1998] <http://www.geo.duke.edu/psds/newyork.htm)

It should be noted, however, that these known expenses pale in comparison to the potential damage of a great hurricane. The unnamed hurricane of September, 1938 that struck Long Island and then southern New England resulted in at least 600 deaths. Damage was catastrophic to what were then largely rural farming and fishing communities on Long Island. Local lore from survivors describe being able to take a boat from the Atlantic shore to the Sound across the western end of Long Island before the waters receded from the storm. Fortunately, with modern weather forecasting, the region is not likely to be unprepared for a great hurricane, however, whether the great number of local residents decide to flee when warned is a grave concern, and the survival potential of modern property and infrastructure is untested. Winter nor'easters are well known to local residents, but their intensity does not rival the potential destruction of a great hurricane.

| Return to Our Transient Coastal Environment. |