66. Island Beach State Park

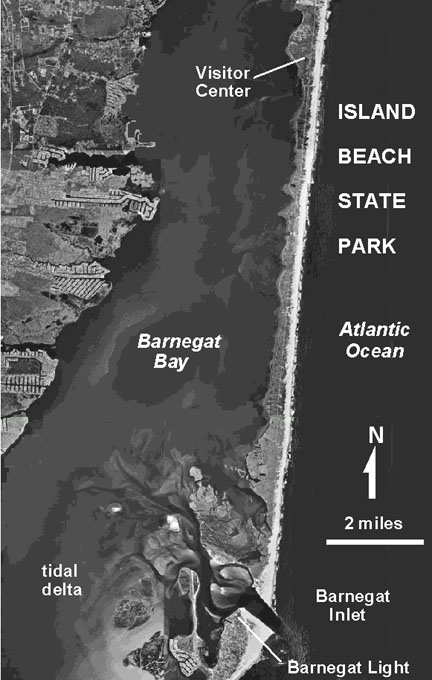

Island Beach State Park is the last remaining stretch of undeveloped barrier island on the central New Jersey coast. The park extends from the shore community of Seaside Park southward for just over seven miles to Barnegat Inlet, a stabilized inlet to Barnegat Bay (Figure 174). To get to Island Beach, take the Garden State Parkway to Toms River (Exit 82A) and follow Route 37 east across the causeway to Seaside Heights. Follow Route 35 south until it dead ends at the park entrance. A daily use fee is required to enter the park.

|

| Figure 174. Aerial photograph map of Island Beach State Park including the tidal delta in Barnegat Bay. |

The barrier island was purchased in 1926 by Henry C. Phipps, a Pittsburgh steel magnate and partner of Andrew Carnegie. His intentions were to build an elaborate resort and beach community. However, the 1929 stock market crash and Mr. Phipps' death in 1931 prevented this scheme. The barrier island remained undeveloped property of his estate until New Jersey purchased the land to establish Island Beach State Park in 1953. The park opened to the public in 1959. The park serves as stark reminder of what the natural shore looked like before development, and serves as an outdoor classroom for processes associated with barrier islands along the Jersey Shore.

The park is subdivided into three zones. The Northern Natural Area is a wildlife preserve next to Seaside Park. It encompasses the area shoreward of the beach to the lagoon, and consists of sand dunes, saltwater marshes, freshwater bogs, and a maritime shrub forest community. Public access to this northern section is limited to beach walking and ocean fishing. Self-guided and ranger-led nature walks through the back beach area begin at the Aeolim Nature Center located a about mile south of the park entrance. The central portion of the park includes two large developed bathing recreational beaches. The Southern Natural Area comprises both the inlet area and a wildlife refuge. There is limited parking and access to the beach. The southern section of the beach is open to beach buggies for fishing by permit. Several small gravel roads lead to a very narrow beach on the bay side of the island. This area is accessible for nature study and hiking only. Be aware that poison ivy and ticks are a threat any time of year. In season, mosquitoes can be ferocious in the back beach area, and lightning is always a serious threat to consider.

A short walk from the Atlantic Ocean beach to Barnegat Bay provides an opportunity to examine all the natural features associated with a barrier island. Compared to area beaches farther north, this beach consists of a nearly pure white quartz sand with only a trace of other minerals. The sand is similar in consistency to the sands exposed in the New Jersey Pine Barrens. Longshore drift is continually moving sand northward along the New Jersey shore. Much of the sand is probably derived for the reworking of older Tertiary and Quaternary marine, beach and barrier island deposits as changes in sea level caused the shoreline to migrate back and forth across the shallow shelf and coastal plain. Evidence for this includes the occasional appearance on the beach of cobble-to-boulder-sized concretions derived from the older underlying sedimentary formations that are exposed offshore.

Island Beach is known for its large back beach sand dunes, particularly along the southern end near Barnegat Inlet. Dunes are constantly building up and shifting, even invading the beach parking areas (Figure 175). Visitors are encouraged not to walk on the dunes so that plants can become established to stabilize them. The existence of the dunes is an indication of the harsh, windy conditions that can occur along the shore, particularly during the winter months. These dunes represent an important natural line of defense against the possibility of a massive assault of a hurricane or nor'easter. Without the dunes, the narrow barrier island might easily be breached, causing even greater destruction inshore.

|

| Figure 175. A coastal dune moves in on a parking lot at Island Beach State Park. |

Barnegat Inlet at the southern end of the beach is an exceptional example of the tidal delta. The features of this tidal inlet can best be appreciated from an aerial view (see Figure 174). Note the bifurcating channels in the shallows on the bay side of the inlet. This is a flood-tidal delta. These channels, sand bars, and islands are constantly changing as daily tidal currents and storms rework the sand deposits. On the ocean side of a natural inlet an ebb-tidal delta may form if longshore currents are not strong enough to destroy them. At Barnegat Inlet the formation of an ebb-tidal delta was largely ameliorated by the construction of jetties on the north and south sides of the inlet. Building the jetties has helped to stabilize the waterway, but has created other enduring problems in the process. If nature were left unhindered, this now massive channel probably would not have grown to its current size. Barnegat Inlet would have eventually filled in, and a new opening to the bay would have eventually formed elsewhere along the shore. However, the northward longshore drift of sand continues. Shortly after the southern jetty was completed on the south side of Barnegat Inlet, longshore drift of sand filled all the available accommodation space. Sediment began to spill again into the channel, contributing to the continued buildup of the tidal delta on the bay side. Likewise, the northern jetty built blocked the northward flow of sand to replenish Island Beach. This has resulted in the shoreward erosion of the barrier island causing it to grow steadily narrower. To alleviate the depletion of beach deposits, a slurry of sand is continuously pumped from the boat channel over the north jetty to replenish sand to the barrier island. The maintenance of the ship channel through the inlet and tidal delta region will be a never-ending project.

Island Beach and Barnegat Bay have endured intense developmental pressure: the shore side of the bay is considered prime real estate. Unfortunately, this development is having a negative impact on the quality of wildlife habitat in the bay. Non-point sources of pollution are of greatest concern. Non-point sources (unlike "point sources" such as sewage treatment plants or landfills) include yard fertilizers and pesticides, septic sewage, motor oil, and other spilled household products that accumulate in the groundwater that discharges into the bay. Consider pet wastes: where one pet may not contribute much, hundreds of thousands of pets in a heavily urbanized area can supply a significant amount of pollution to the bay! Also, the ever-increasing volume of treated municipal waste water approaches or surpasses the natural supply of freshwater during the dryer late summer and fall months. This unnatural supply of water is diluting portions of the bay beyond the tolerance level of some species, thus threatening the entire ecosystem.

| Click here to continue to next page. |

| Return to the Field Trips to the Shore page. |

| Return to Geology of NYC Region Home Page. |

| Return to Our Transient Coastal Environment. |