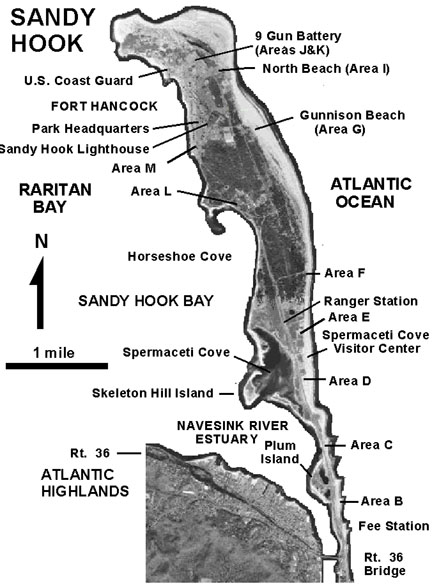

Sandy Hook is located at the intersection of the New Jersey shore with the ancient valley of the combined Raritan and Hudson Rivers now flooded as Raritan Bay. Sandy Hook is a spit built by the northward longshore drift of sand along the Jersey Coast, supplemented by sediments derived from the Shrewsbury and Navesink Rivers estuary (Figure 176). Both Giovanni da Verrazano and Henry Hudson described going ashore on the spit. Historical legend reports that the pirate, Captain Kidd, supposedly buried treasure which remains undiscovered. This natural barrier to the harbor has a long military history, and is the site of numerous maritime disasters and heroic rescue operations. Massive armored fortifications of Fort Hancock were built at the end of the 19th century as deterrents for foreign invasions following the Spanish American War. Most of the construction occurred between 1894 and 1910. Fort Hancock was the site of Nike nuclear missile batteries built in the 1950s. The fort was decommissioned in 1972 and given to the National Park Service for inclusion into Gateway National Recreation Area; only a small portion of the point is still a part of a U.S. Coast Guard facility.

|

| Figure 176. Aerial photograph map of Sandy Hook, New Jersey. |

A trip to Sandy Hook is a pleasure any time of year. To get there take the Garden State Parkway to Exit 117 and follow Route 36 south and east through the Atlantic Highlands. Route 36 crosses the Navesink River Drawbridge at Seabright. Follow the signs to the park as you cross the bridge. Before or after your Sandy Hook visit you might consider stopping at the Mount Mitchell Overlook in Highlands, New Jersey, or climbing to the top of the lighthouse at the Twin Lights Museum. Both locations offer spectacular views of the spit, Raritan Bay, Staten Island, and the City to the north and west (Figure 177). A combination of a ferry ride from the City to Highlands, NJ and then a bus ride to the park is also an option.

|

| Figure 177. View of Sandy Hook from the lighthouse observation deck at Twin Lights Museum in Highlands, New Jersey. Note the Manhattan skyline in the distance. |

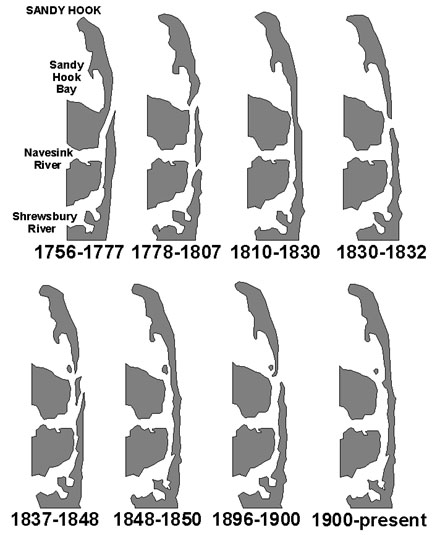

Sandy Hook has a long, rich history of occupation and land use. Historical maps show a constantly changing landscape through time (Figure 178). Natural processes affecting Sandy Hook dwarf the temporal modification by man. Sandy Hook Lighthouse, completed in 1764, was built on the northern end of the spit; it now stands nearly a mile and a half south from the current tip. Several times in Sandy Hook's historic past, major storms have breached the narrow barrier turning the spit into an island. At different times in its history Sandy Hook was attached to the mainland north of where the Navesink and Shrewsbury Rivers currently drain to the sea.

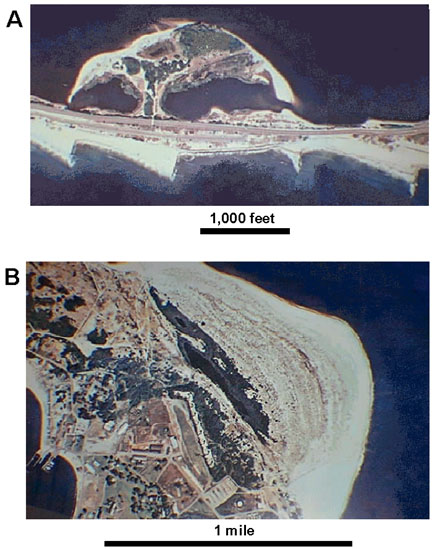

Sandy Hook is an exceptional place to study modern depositional processes. The ocean side of the spit consists of storm-dominated beaches with well developed shore dunes (where they haven't been destroyed or eroded away). The northward longshore drift is evident by the buildup of sand on the south side of several groins that jut seaward from the beach. Several of these groins are located in the vicinity of the parking area (A) near the park entrance (Figure 179A). These groins were completely buried during a beach sand replenishment operation in the early 1990s (Figure 180), however, they are gradually becoming exhumed by erosion.

The beach is constantly changing from season to season. During winter months, the beach typically has a steeper profile. From the late fall to early spring the beach displays an abundance of quartz pebble-dominated gravel, along with concretions and anthropogenic materials of all kinds. The nearly constant wind blowing across the back beach area during the winter builds up a thin intermittent layer of heavy mineral sands rich in garnet, magnetite, hematite, and other minerals. During the summer the gravel and the heavy mineral sand diminishes in quantity or vanishes altogether.

|

| Figure 178. Maps showing the progressive shoreline changes at Sandy Hook (after NPS Spermaceti Cove Visitor Center display). |

|

| Figure 179. Sedimentation features on aerial photographs of Sandy

Hook: A. Plum Island represents the remnants of a washover fan. The

sawtooth pattern along the Atlantic Ocean side reveals the buildup

of sand adjacent to stone groins transported northward by longshore

drift. B. an accretionary sandy buildup on the northern tip of the spit. The large dark area is a newly-formed freshwater pond. The dotted straight line is the 9 Gun Batter completed in 1902. |

|

| Figure 180. A sand replenishment operation along the seawall in Seabright, New Jersey just south of Sandy Hook. Note the lack of beach along the seawall south of the beach-building operation. |

The bay side of the spit is most affected by tidal currents and waves generated by winds across Raritan Bay. There are several tidal current-constructed sand bars and small islands of the bay side near the mouth of the Navesink River. Plum Island in Raritan Bay (near parking area A) is a remnant of an old tidal inlet formed by several intense storms that separated Sandy Hook from the mainland in the 1800s (see Figure 179A). Along the west side of the peninsula are a couple of tidal creeks draining salt marshes. One is accessible via a boardwalk west of the Spermaceti Cove Visitor Center. Another is accessible near at the north end of Horseshoe Cove (Figure 181).

|

| Figure 181. A tidal creek and salt marsh. A salt cedar forest is developed amongst the bayside dunes in the distance. Raritan Bay is to the right. The telephone pole-like platform is an artificial osprey nest. Marine invertebrate species that inhabit the bay side are almost completely different than the open ocean side of the spit. |

The central portion of Sandy Hook is covered with a thick growth of a maritime shrub forest. The sandy substrate of ancient beach and dune deposits is host to mature holly and juniper (red cedar) forests throughout the undeveloped inland areas. Some holly trees are over 150 years old. These old trees can be seen along the roads in the park's central region. A nature trail through the shore dunes and maritime shrub forest also begins at the Visitor Center.

Some of the best evidence for coastal erosion can be seen along Raritan Bay side of the spit just north of Spermaceti Cove (Figure 182). About four miles north of the park entrance (just past the Ranger Station) is a parking area in the middle of the divided road. A short walk to the north there is a closed park road leading west to Battery Mills (completed in 1912) along the shore of Horseshoe Bay. On the bay a wooden seawall and a few large concrete bunkers were built. Erosion has since carved the shoreline back nearly 150 feet, leaving the old wooden posts of the seawall standing offshore, causing the bunkers to sink into the water. Near the bunkers erosion has carved downward exposing a layer of ironstone (a tightly limonite and goethite-cemented cross-bedded sandy gravel) probably representing an early Holocene tidal channel or sand bar.

|

| Figure 182. An early 20th century military bunker likes exposed to the wave on Raritan Bay. The line of posts on the right represents an old shoreline seawall built around 1910. The shoreline has eroded back almost 200 feet. The dark rocks in the foreground are tightly iron-cemented conglomerate formed in Late Pleistocene or Early Holocene gravel deposits. |

Another short walk begins at Parking Area K at the northern tip of the island next to the 9 Gun Battery. A trail leads northward about a tenth of a mile to an observation deck built atop a large sand dune. The deck provides a view of new land accreted onto the end of Sandy Hook since about the time that the battery built between 1898-1902. In this area there is a pond that formed when a smaller spit built northward around a bend in the hook. As the spit continued to grow the pond eventually changed from saltwater to freshwater (see Figure 179B).

Along the narrow, southern part of the spit, a great seawall has been built in an attempt to prevent the destruction of property in Seabright and other shore communities, to protect the shipping channel, and to prevent Sandy Hook from becoming an island again. The Seabright seawall has a long history of controversy. Millions of dollars have been spent on numerous occasions to replenish sand to the beach side of the seawall. Erosion eventually strips away the sand, usually during a single major storm event, or over a series of winter storms. Longshore drift carries this sand seaward to offshore bars, or northward where some accumulates along the northern tip of Sandy Hook, while some eventually finds its way to the shipping channels (adding to the necessity for additional dredging operations).

No doubt the expense and heartbreak of disaster along the shore will continue indefinitely. Before the most recent sand replenishment operation in the mid 1990s, the beach was completely eroded away from seaside portions of the seawall, exposing the underlying Gardeners Clay to erosion. For a while before the beach building project began, concretions bearing fossils derived from the Gardeners Clay were quite abundant on the beach (see Figure 148). Many of these concretions bear shells and crustacean remains, while some preserve tree roots, indicating a period when sea level was lower.

The age of Sandy Hook is unresolved. This is partly because the history of sea level change and isostatic rebound are not clearly established. The right angle geometry of the Atlantic Highlands to the Jersey Shore is an indication that the combined Hudson and Raritan River channel once flowed in the vicinity of Sandy Hook. The hills of the Atlantic Highlands area represent the former south side of the river valley. Likewise, the Navesink and Shrewsbury Rivers flowed directly eastward when sea level was lower. In the offshore area near Shrewsbury are a series of submerged outcrops called the "Shrewsbury Rocks." These submerged outcrops survived the recent marine transgression. Whether they consist of older Tertiary rock formations or represent younger Pleistocene or Early Holocene well-cemented barrier island deposits is unclear. These outcrops are probably the source of many of the concretions washing up on Sandy Hook. It is interesting to add that the Shrewsbury Rocks were a site of numerous harsh, verbal battles between lobster trappers and fishermen, both taking advantage of the rich sea life attracted to the submerged outcroppings. A very old man who was the grandson of a fisherman told us that in the late 1800s the water offshore from Sandy Hook was so clear that his grandfather could look down into the water and see the white tops of these submerged outcrops. The white color was from the abundance of encrusting stony coral that covered the outcrops. Fragments of stony coral can frequently be found on the beach at Sandy Hook. The seabed's slope offshore from Sandy Hook if fairly steep. If ancestral barrier islands formed late in the Pleistocene, they probably simply migrated shoreward as sea level has progressively risen, becoming part of the modern Sandy Hook.

| Return to Our Transient Coastal Environment. |