Regional Geology of North America |

|

Coast Ranges Provinces |

Click on images for a

larger view. |

The Coast Ranges of Oregon and California are rugged mountainous country with complex geology. Most of the region is new land that has formed since Mesozoic time by the tectonic actions involving subduction and accretion of small landmasses and pieces of ocean crust that were pushed onto the continental margin rather than being subducted. The Coast Ranges are subdivided into sections including, from north to south, the Oregon Coast Ranges, the Kamath Mountains (straddling the Oregon California border), the Northern Coast Ranges (extends southward from Crescent City, California the Northern San Francisco Bay Area), the Southern Coast Ranges (between San Francisco and Santa Barbara), the Transverse Ranges (between Santa Barbara and Los Angeles), and the Peninsular Ranges that extend from Los Angeles to the southern tip of Baja California. South of Cape Mendicino, the San Andreas Fault and other regional faults are important to the geography and natural history of the Coast Ranges (Figure 253).

Oregon Coast Ranges

Oregon Coast Ranges extend from the Columbia River south into northern California where they transition into the Klamath Mountains and the Northern Coast Ranges of California. North of Cape Mendicino near Cape Mendicino the Cascadia Subduction Zone is actively contributing materials that are being pushed up into the ranges. In Oregon the Coast Ranges are about 30 to 60 miles wide and have an average elevation of about 1,500 feet. The rocks exposed in the Oregon Coast ranges are mostly Tertiary age fore-arc basin deposits. |

Fig. 253. Physiographic provinces and geology of California. |

Klamath Mountains

The Klamath Mountains straddle the Oregon-California border and are both geologically older and distinct, and higher than the other Coast Ranges north and south (Figure 254). The region hosts coniferous forests features and higher mountain ranges than the other Coast Ranges including the Trinity Alps, Trinity Mountains, Siskiyou Mountains, and Marble Mountains, with higher peaks rising above 8,000 to 9,000 feet. With the higher elevations, the region receives higher precipitation rates, mostly in the winter months with high snow fall rates. The Klamath Mountains are composed of “terranes”—slivers of ocean crust, island masses, and blocks of continental crust. Between 260 million (Late Permian) and 190 million (Early Jurassic) years ago a succession of eight terranes were rafted in by the Farallon Plate and accreted onto the continental margin. These terranes were metamorphosed and intruded by magmatic plutons, creating a very diverse suite of rocks with marble, serpentinite, and gabbroic to granitic intrusive igneous being most abundant. One of the marble-bearing terranes is host to Oregon Caves National Monument and Preserve. |

|

| Fig. 254. The Klamath Mountains straddle the Oregon-California border and are higher and older than the other Coast Ranges. |

Northern Coast Ranges of California

The Northern Coast Ranges run north-to-south, generally parallel to the coast. U.S. Highway 101 (the Coast Highway) runs along valleys between Inner and Outer ranges, separated by the river valleys of the Eel River to the north, and the Russian River to the south. The outer ranges run to the coast and are wetter and are mostly forested with Coast Redwoods, Ponderosa Pine, and deciduous forests (Redwoods National Park is along the coast between Crescent City and Arcada, California). The inner ranges border the Great Valley are dryer with mixed evergreen and oak woodlands, and chaparral.

Bedrock in the North Coast Ranges are mostly Jurassic, Cretaceous and Tertiary rocks derived from terranes and ocean crust scraped from the Farallon Plate before the San Andreas Fault propagated across the region north of San Francisco starting about 12 million years ago (Late Miocene). The Northern Coast Ranges are mostly below 2,000 feet, but some peaks are higher. Cobb Mountain, elevation 4,724, is the highest.

The Northern Coast Ranges are host to two volcanic fields. The Sonoma Volcanic Field is located at the northern end of the Napa and Sonoma Valleys and was most active during Pliocene time. Its residual heat is illustrated by the Calistoga Geyser, often called the “Old Faithful Geyser of California” (Figure 255). The Clear Lake Volcanic Field is about 90 miles of San Francisco is has been active through Pleistocene time with the most recent volcanism about 11,000 years ago. The Clear Lake Volcanic Field is now host to the world’s most productive geothermal energy power plants, supplying enough electricity for about 850,000 homes in the region. |

Fig. 255. Calistoga Geyser, "Old Faithful Geyser of California" in northern Napa Valley. |

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 256. A "marine layer" (fog bank) settled in in Northern Coast Range in Humboldt County, California. |

Fig. 257.The Mendicino Range and Mayacama Mountains are outer ranges that extend south into Sonoma County. |

Fig. 258. Mount Hood, elevation 2,750 feet, rises above Napa Valley, the premiere wine growing region. |

Fig. 259. Mt. Tamalpais, southernmost peak in the Northern Coast Ranges, overlooks San Francisco Bay. |

|

San Francisco Bay Region

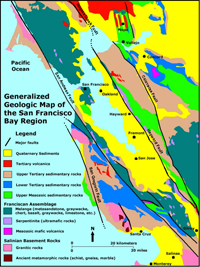

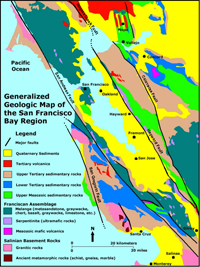

Despite hosting more than 7 million people in 9 counties and over 100 incorporated cities, most of the land is set aside as open space preserves and parklands. Most of the urban development is in the lowlands surrounding San Francisco Bay. Rocks in the region are mostly Jurassic, Cretaceous, and Tertiary age, consisting of belts of rock associated with fault-bounded terranes (Figure 260). Hazards associated with fire, landslides, and earthquake faults make building in the mountainous areas largely unpractical. The San Andreas Fault, Hayward Fault, Calaveras Fault, and San Gregorio Faults are major earthquake faults that have produced significant earthquakes in the region. San Francisco Bay floods that ancestral Sacramento River Valley where it carved its Golden Gate canyon through the Coast Ranges when sea level was almost 400 feet lower during the Pleistocene ice ages. The Golden Gate Bridge spans the bay between San Francisco and the Marin Headlands in Marin County (Figure 261). Golden Gate National Recreation Area encompasses parklands on both sides of the Golden Gate. North of the Bay are Muir Woods National Monument, a redwoods preserve, and Point Reyes National Seashore (Figure 262). Point Reyes Peninsula is a terrane on the west side of the San Andreas Fault and are part of the Salinian Block. The Salinian Block is composed of continental crustal rocks, mostly granite and marble basement rocks overlain by younger sedimentary formations. The Salinian Block shares its origin with the rocks in the Sierra Nevada Range—both were part of the ancestral Cordilleran volcanic arc that developed in the Mesozoic Era. Bedrock east of the Salinian Block consist of the Franciscan Formation—the formation is composed of a mix of rocks derived from ocean crust and deep ocean sediments derived from the ancestral Farallon Plate. Fault-bounded blocks of both Salinian and Franciscan materials have moved northward along fault systems along the California coast, in some cases by hundreds of miles since their time origin (see Figure 248). |

Fig. 260. Map of the San Francisco Bay region showing geology and major faults. |

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 261.The Golden Gate Bridge crosses the narrows of San Francisco Harbor between the highlands of San Francisco and the Marin Headlands |

Fig. 262.Headlands and Coves at Point Reyes National Seashore. Point Reyes is a part of the Salinian Block on the west side of the San Andreas Fault. |

Fig. 263. Montara Mountain on the San Francisco Peninsula coast in San Mateo County is composed of a large block of Salinian granite. |

Fig. 261. Pigeon Point along the coast of San Francisco Peninsula is part of a Sur Series terrane located on the west side of the San Gregorio Fault. |

|

Santa Cruz Mountains and Santa Clara Valley

The north end of the Santa Cruz Mountains begins where the San Andreas Fault comes onshore near Daly City. Montara Mountain at the north end of the range is a massive exposure of Salinian granitic basement on the west side of the fault (Figure 263). The Santa Cruz Mountains stretch for 80 miles south to the Pajaro River Gap near Watsonville. The Santa Cruz Mountains and started rising above sea level about 4 million years ago, pushed up by compression created by a large bend in the San Andreas Fault. The east side of the Salinian Block is the San Andreas Fault; the west side of the block is bounded by the San Gregorio Fault—the fault comes onshore near Half Moon Bay and again at Pigeon Point (Figure 264). The city of Santa Cruz is developed on the elevated marine terraces on the southern flank of the mountains. The Santa Cruz Mountains on the San Francisco Peninsula are mostly preserved as parklands, open space preserves, watershed for regional cities and several Coast Redwood preserves (Figure 265).

The Santa Clara Valley runs roughly south and east of southern San Francisco Bay, entrenched between the Santa Cruz Mountains and the Diablo Range to the east. San Jose (a large part of “Silicon Valley”) is situated at the north end of the valley. San Jose was started, in part, with commerce supporting the mining of mercury (supplying mercury need for the California Gold Rush). The mercury comes from mineralized veins associated with serpentinite in the New Almaden Mining District in the eastern foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains. Mt. Umunhum (elevation 3,486 feet;1,063 m) and Loma Prieta (elevation 3,786 feet; 1,154 m) are high point in the range along the Sierra Azul Ridge that runs along the east side of the San Andreas Fault (Figures 266 and 267). Rocks of several terranes and different ages make up the Franciscan Basement rock throughout the Santa Clara Valley. South of the Pajaro Gap (canyon of the Pajaro River), the San Andreas Fault runs down the east side of the Gabilan Range to where it converges with the Calaveras Fault south of Hollister at the southern end of the valley. Mission San Juan Bautista was built near Pajaro Gap on the fault scarp of the San Andreas Fault—it became the first “earthquake-engineered” building in the United States (Figure 268). To the south, the San Andreas Fault then roughly parallels the canyons and valleys of San Benito River south between the Diablo Range (on the east) and the Gavilan Range (to the west).

|

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 265. A forest of giant redwoods are preserved in Big Basin State Park in the Santa Cruz Mountains between San Jose and Santa Cruz. |

Fig. 266. Manzanita grows on serpentinite in the foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains east of Mt. Umunhum and Sierra Azul Ridge (in the distance) |

Fig. 267. Santa Clara Valley with El Toro [Peak] near Morgan Hill, California and Loma Prieta Peak and Sierra Azul Ridge in the distance. |

Fig. 268. The historic El Camino Real runs along the rupture scarp of the San Andreas Fault next to Mission San Juan Bautista. |

|

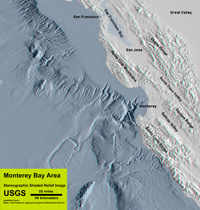

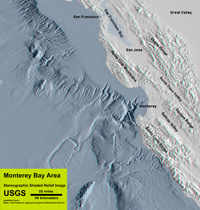

Monterey Bay Region

Monterey Bay is at arc-shaped bay at the head of Monterey Canyon, a 10,000 foot deep submarine canyon that descends into abyssal depths offshore. The canyon is at the mouths of the Pajaro and Salinas Rivers between the cities of Santa Cruz and Monterey (Figure 269). The Santa Lucia Range runs roughly north-south along the coast south of Monterey; its steep western slope is called the Big Sur (Figure 270). The San Gregorio-Hosgri Fault runs along the coast offshore of the Big Sur. The Salinas Valley is bordered by the Santa Lucia Range on the west and Gabilan Range on the east. Arroyo Seco (meaning "dry wash") drains from a canyon the eastern side of the Santa Lucia Range into the broad valley of the Salinas River Valley (Figure 271). Junipero Serra Peak, elevation 5,857 feet, is the highest in the high peaks portion of the Santa Lucia Range.

Fremont Peak (elevation 3,455 feet) was named after John C. Fremont, the military explorer who planted a US flag on the peak in 1848 before fleeing to Oregon to escape from a Mexican army. Fremont Peak is the highest peak at the north end of the Gavilan Range (Figure 272). The top of the mountain is a great block of marble of late Paleozoic age. Both the Santa Lucia and Gabilan Ranges are part of the Salinian Block on the east side of the San Andreas Fault. Pinnacles National Park is at the south end of the Gabilan Range (Figure 273). The Pinnacles are the eroded remnant of half of a volcano that formed about 23 million years ago on the San Andreas Fault. The other half of the Pinnacles formation is preserved a the Neenach Formation 195 miles south in the western Tehachapi Mountains. |

Fig. 269. Shaded relief map showing bathymetry and topography of mountain ranges and valleys the greater Monterey Bay region. |

| Fig. 274. View looking south along the crest of the Gabilan Range showing the anticline structure of Salinian Basement exposed in the core of the range. |

The Diablo Range

The Diablo Range is the belt of mountains on the east side of the Santa Clara Valley and San Benito River Valley to the south. Geologically, the Diablo Range is on the east side of the Calaveras Fault and San Andreas Fault at its southern end. The range extends south from the Carquinez Straight in the East Bay and Sacramento River Delta region. The range runs south along the west side of the Great Valley to the Carrizo Plain. Mt. Diablo (elevation 3,889 feet; 1,185 m) is a high peak at the north end of the range. Mount Hamilton (elevation 4,260 feet; 1,300 m) is near San Jose is home of the historic Lick Observatory. San Benito Mountain (elevation 5,241 feet ; 1,597 m) is the highest peak in the southern end of the Diablo Range. Most of the rest of the range is within elevations of 1,500 to 3,000 feet. Bedrock in the Diablo Range consists of Franciscan Basement rocks (with serpentinite) and where present, overlain by the Great Valley Sequence and younger Tertiary sedimentary rocks (Figure 275). Physical landscape features associated with San Andreas Fault system stand out along the surface ruptures (Figure 276). The town of Parkfield (population of a couple dozen) is one of several towns to claim it is the "Earthquake Capitol of the World" (Figures 277 and 278). |

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 275. Franciscan basement with serpentinite overlain by Great Valley Sequence in the Diablo Range south of Pinnacles National Park. |

Fig. 276. Sag Pond next to fault scarp along the San Andreas Fault in the Diablo Range between Coaling and King City, CA. |

Fig. 277. Parkfield, California, claims to Earthquake Capital of the World. It experiences a major earthquake about every 20 years. |

Fig. 278. This bridge over Cholame Creek in Parkfield, California displays offset warping by motion because it crosses the San Andreas Fault. |

|

| https://gotbooks.miracosta.edu/geology/regions/coast_ranges.html 1/20/2017 |

|

|

|

|