Palomar Mountain is an excellent destination for day hikers and campers wanting to get out to see forests, mountain scenery, sunsets, and night skies away from urban lighting and noise of Southern California cities.

Palomar Mountain is home to the historic Palomar Observatory (Figure 1). The Observatory is owned and operated by CalTech. It has been in operation since the 1930s and remains a significant contributor to astronomical research.

Palomar Mountain State Park is a nature preserve with picnic and camping facilities. The park is host to unique sub-alpine, mixed conifer and deciduous forests and open meadows accessible by a many miles of hiking trails. Much of Palomar Mountain is within the Cleveland National Forest. The mountain summit area is accessible by two roads, the South Grade Road (S6) and East Grade Road (S7); both roads intersect Ca Highway 76 (see maps below). Roads leading to the Observatory and State Park merge near the intersection of routes S6 and S7. Scenic overlooks along the East Grade Road porvide with views of the regional landscape. Be sure to get gas before attempting to drive to this remote area. |

Click on images for a larger view. |

Fig. 1. Palomar Observatory on Palomar Mountain.

|

A1

Topographic, Satellite, and Geologic Maps of the Palomar Mountain Area

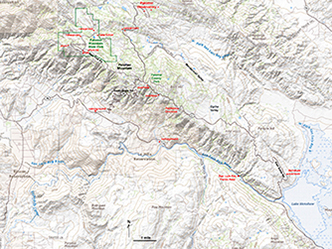

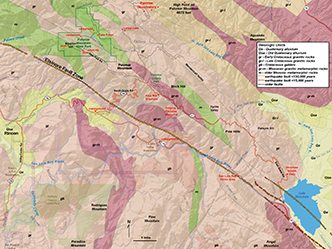

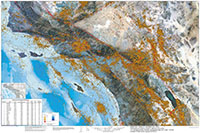

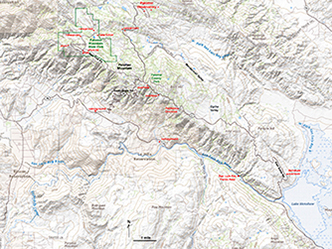

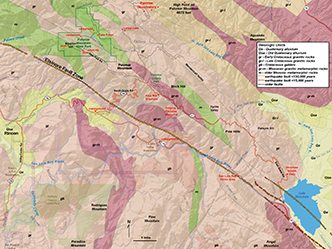

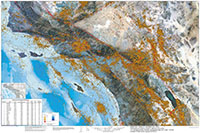

Palomar Mountain is located in the core of the Peninsular Ranges in northern San Diego County (Figure 2). Figure 3 is a topographic map that shows geographic features including the location of Palomar Mountain State Park, picnic areas, campgrounds, the Palomar Observatory, roads, streams, and landscape feature. Figure 4 is a satellite image map that shows the dark vegetation on the mountainsides in contrast to the meadows and grasslands in the valleys. Much of the forested areas are part of the Cleveland National Forest. Figure 5 is a geologic map of the Palomar Mountain area that shows the active earthquake faults and other mapped faults in the vicinity. Colors on the map correspond to general classes of bedrock of different ages in the area. The map has a legend that shows what the bedrock colors and lines on the map illustrate. |

Fig. 2. Palomar Mountain field trip area (location map). |

Fig. 3. Topographic map of the Palomar Mountain area. |

Fig. 4. Satellite map of the Palomar Mountain area showing the location of the Elsinore Fault.

|

Fig. 5. Geologic map of the Palomar Mountain area. |

A2

Geology of the Palomar Mountain Area

Palomar Mountain owes its existence to the formation of Peninsular Ranges Batholith during the Mesozoic Era This was followed by the tectonic forces that have resulted in the development of the Elsinore Fault Zone, a major strike-slip earthquake fault that cuts diagonally across the Peninsular Ranges. Palomar Mountain is an uplifted crustal block (a pressure ridge) that rises to elevations of 5,000 to more than 6,000 feet along the northeast side of the Elsinore Fault Zone valley. Figure 6 illustrates that there are numerous small earthquakes associated with the fault zone—the label for the Elsinore Fault Zone on the earthquake map is in the vicinity of Palomar Mountain. Note that in the vicinity of Palomar Mountain there are two clusters of epicenters—one is distributed on the northeast side of the fault, the other is on the southwest side of the fault near the Henshaw Lake end of the mountain. Epicenters dominating one side of a fault suggest the fault plain dips in that direction at depth. The earthquake data also reveal information about bends in the fault zone that may result in compressional uplift or tensional subsidence, and areas locations where the fault zone may be locked. |

Fig. 6. SoCal earthquake epicenters, 1970-2010. A label for the Elsinore Fault Zone has been added to the map near Palomar Mountain. |

A3

Rocks on Palomar Mountain

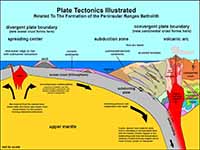

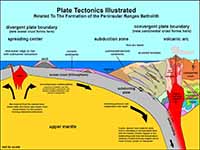

Figure 7 is a generalized plate-tectonics diagram that illustrates how the Peninsular Ranges Batholith formed. Palomar Mountain is straddles the boundary between two geologic provinces: the Western Belt and Eastern Belt of the Peninsular Ranges Batholith. The Western Belt is dominated by gabbroic and granitic intrusive igneous rocks of 120-105 million years age (Early Cretaceous). These rocks are shown as the pink areas and labeled gr on the geologic map. The Eastern Belt is dominated by granitic intrusive igneous rocks of about 98-93 million years age (early Late Cretaceous). These rocks are shown as the orange areas and labeled gr-l on the geologic map.These igneous rocks crystallized in plutons that had intruded into older metamorphic and igneous rocks that predate the formation of the batholith. These rocks are ossibly Jurassic, Triassic, or even Late Paleozoic in age (shown as purple and green areas on the geologic map). These rocks probably were ancient seafloor sedimentary and igneous rocks that have been completely altered from their original form. These metamorphic rocks include gneisses, schists, and migmatite (a complex mix of igneous and metamorphic rocks). These have been sheared, broken up, compressed, and partially re-melted back together before being intruded again with igneous materials when the batholith formed later in Cretaceous time. Examples of these rocks are illustrated below.

|

Fig. 7. Plate tectonics model illustrating the origin of the Peninsular Ranges Batholith along a convergent plate boundary with a subduction zone.

|

There are numerous exposures of Cretaceous-age granitic rocks in road cuts along the East Grade Road on Palomar Mountain. Figures 8 to 12 show images of the deeply weathered, light-colored granitic rock (Western Belt granite) that are cut by white pegmatite dikes. The pegmatite dike formed in the late stages of the cooling (and shrinking and cracking) of the large granite plutons that formed the batholith where fluids are injected into fractures. The granite is heavily locally fractured. It also locally included dark inclusions or blocks of older rocks that survived melting in the massive magma bodies that crystallized into granite (an example is in Figure 13).

Figures 14 to 19 show examples of older rocks exposed in Palomar Mountain State Park (typical of purple and green colors on the geologic map). These are the older metamorphic and igneous rocks that predate the Cretaceous granitic rocks. These rock are more mafic in composition that younger granite and are locally heavily deformed, displaying shearing structures and partial melting (migmatite).

|

Fig. 8. Pegmatite dike in granite along West Grade Road at Pica Mik Overlook. |

Fig. 9. Pegmatite vein in fractured granite in road cut along East Grade Road. |

Fig. 10. Pegmatite dikes stand out on a weathered granite road cut. |

Fig. 11. Pegmatite dike in weathered granite in an East Grade Road cut. |

Fig. 12. Close-up view of pegmatite dike (or rhyolite dike) in granite. |

Fig. 13. Gabbro inclusion in fractures granite exposed in an East Grade Road cut. |

Fig. 14. Granite-gneiss outcrops near the Silvercrest Picnic Area. |

Fig. 15. Gneiss (gabbroic metamorphic rick cut by a light-colored aplite dike). |

Fig. 16. Shear zone in gneiss and schist outcrop near the Silvercrest Picnic Area. |

Fig. 17. Migmatite, gneiss showing shearing in flow structure. |

Fig. 18. Migmatite composed of mostly biotite schist with a coarse gabbro dike. |

Fig. 19. Migmatite outcrop with gabbro inclusions in sheared biotite schist. |

|

A4

Elsinore Fault Zone And Associated Landscape Structures

The Elsinore Fault Zone runs along the southwestern flank of Palomar Mountain. The fault is a strike-slip fault with right-lateral (dextral shear) displacement—the crustal block on the west side of the fault zone is moving northward relative to the east side. Studies of the fault zone have documented Holocene earthquake activity (with rupture displacement). The long-term slip rate is estimated about 4-5 millimeters per year (Treiman, 1998). Total displacement since the fault developed in late Tertiary time is uncertain, but is in a range between 10 and 40 kilometers. |

Figure 20 shows the physiographic regions in San Diego County. The Elsinore Fault defines the boundary between the stable Santa Ana tectonic block on the west and the Fault-Bounded Blocks and Basins region to the east. The Salton Sea basin farther to the east is part of the expanding rift associated with the San Andreas Fault System and the Gulf of California.

There is also a vertical component to the fault movement that has resulted the rise of the Palomar Mountain ridgeline (an uplifted crustal block). The Palomar Mountain ridgeline is nearly 2,000 feet higher than the the peaks and mesa on the east side of the fault zone valley. Preferential erosion over millions of years by the San Luis Rey River and its tributaries have carved a linear valley along the southwestern side of Palomar Mountain. This fault valley basically follows Highway 76 from Lake Henshaw Dam westward to the Pauma valley near Rincon. Doane Valley (in the state park) and Mendenhall Valley are also linear valleys associated with erosion along fault zones. |

Fig. 20. The Elsinore Fault Zone defines the NE edge of the Santa Ana tectonic block. |

Views Along The Elsinore Fault Zone Valley On The South Side Of Palomar Mountain

Figures 21 to 29 are a series of view along and across the structural/erosional valley of the Elsinore Fault Zone, starting in the east near Lake Henshaw and proceeding westward to the Pauma Valley near Rincon, California.

Figures 21 and 22 are views looking southeast along the Elsinore Fault Zone where it leaves the San Luis River Valleyand cuts across the Lake Henshaw Basin. From there the fault cuts across the western flank of the Vulcan Mountains. On the distant horizon, the Elsinore cuts through a the gap (near Julian) with the Vulcan Mountains on the left (east) and the Cuyamaca Mountains on the right (west). From there, the fault descends into the Anza Borrego desert region through Banner Canyon before merging with other fault in the souuthern Imperial Valley.

Figure 23 and 24 are views looking down into the fault valley where the San Luis Rey river cuts through elevated river terraces (with fields) and descends into the series of fault- or fracture-zone controlled switchbacks in the narrow river gorge.

Figures 25 and 26 show views of the linear features in the fault valley in the vicinity where the South Grade Road intersects Highway 76. Fault scarps and side-hill benches are revealed by changes in slope and changes in vegetation (reflecting differences in the composition of the soil and bedrock underneath).

Figure 27 and 28 show the western end of the fault valley. Pala Mountain displays a unusually large linear band of granite running across its northern flank. Figure 28 shows a series of curves in Highway 76 as it descends along the fault valley into the Pauma Valley near Rincon, California. The Elsinore Fault Zone continues northward through Temecula, Murietta, through Lake Elsinore, and northward into the Los Angeles region where it merges with other faults.

Figure 29 is a panoramic view looking south from Boucher Point in the state park that takes in a sweeping view of the coastal mesas and hills in the region referred to as the Area of the "Old Erosion Surface" on the Santa Ana tectonic block west of the Elsinore Fault Zone.

|

Fig. 21. View looking west toward the Elsinore Fault valley near Lake Henshaw. |

Fig. 22. View west along the Elsinore Fault valley with distant Cuyamaca Mountains. |

Fig. 23. San Luis Rey River gorge and elevated river terraces. |

Fig. 24. Zoom view of the San Luis Rey River gorge and elevated river terraces . |

Fig. 25. View looking east along the Elsinore Fault Valley from overlook on South Grade Road. |

Fig. 26. View looking west along the Elsinore Fault Valley from overlook on South Grade Road. |

Fig. 27. Zoom view west from Boucher Lookout toward Pala Mountain in the Hellhole Canyon County Park. |

Fig. 28. View showing Highway 76 descending along the fault zone into Pauma Valley near Rincon. |

|

Fig. 29. Panoramic view to the south and west from Boucher Lookout Tower area. This view is looking across the stable Santa Ana tectonic block toward the Pacific Ocean. The name, Area Of "Old Erosion Surface" refers to the character of this region that preserves characteristics of an ancient pediment surface. This ancient erosion surface once extended from the volcanic highlands region of Sonora, Mexico all the way to the coastal plain/continental shelf region of the San Diego coastline. Since mid-Tertiary time, this region split away from Mexico has been slowly drifting northward as a coherent tectonic block along with the entire Baja Peninsula. It is riding northward attached to the Pacific Plate. The Santa Ana tectonic block has also been very slowly rising, allowing streams to incise into there valleys, resulting in an erosionally-dissected plateau. Isolated coastal mountains on the Santa Ana tectonic block are monadnocks (remnants of ancient mountains) that locally rise above the ancient pediment surface. Near the coast, the mesas regions are remnants of the wave-cut surfaces associated with embayments on the ancient continental shelf. These mesas are part of the regions referred to as the Area of High Terraces and Area of Coastal Plain Terraces shown on Figure 20.

|

A5

Palomar Mountain State Park

Palomar Mountain State Park encompasses 1,862 acres along the northwestern end of Palomar Mountain. The park is known for its scenic pristine forests and and mountain meadows. Information about the park campgrounds, picnic areas, trails, facilities, and park rules can be found on the websites:

Palomar Mountain State Park and Park Brochure. These locations are on the park map (Figure 30).

Tree species on Palomar Mountain include Black Oak, Canyon Live Oak, Coast Live Oak, Incense Cedar, Ponderosa Pine, Douglas Fir, White Fir, and Big-Cone Pine (Colter Pine). Parts of the forest appear to be old growth, but the area has experienced selective logging and extensive wildfires in the past. The discussions and photo galleries below illustrate the amazing variety of forested landscapes and meadows, and other features in the park. |

Fig. 30. Map of Palomar Mountain State Park. |

A6

Silvercrest Picnic Area

(Palomar Mountain State Park)

The Silvercrest Picnic Area is a worthwhile area to explore. It is located close to the park's Ranger Station (entrance station).

The picnic area is located within a grove of ancient (and large) Incense Cedars trees (Figures 31 to 37). One of the largest has been dated to being over 400 years old. Adjacent to the picnic area is an area of outcrops of granite and gneiss that preserve morteros (well-worn mortar holes carved into the stone used for the grinding of acorns and seeds, Figures 38 to 41). It is interesting to ponder how communities of ancestral American Indians utilized the natural resources this mountaintop area for countless generations. See the Friends of Palomar Mountain State Park website for a discussion about the cultural history of the area. |

Fig. 31. The Silvercrest Picnic Area is close to the Ranger Office/Entrance Station. |

Fig. 32. This large Incense Cedar is in the Silvercrest Picnic Area.

|

Fig. 33. This Incense Cedar at Silvercrest Picnic Area isestimated 400 years old. |

Fig. 34. Picnic tables near the ancient Incense Cedar at Silvercrest Picnic Area. |

Fig. 35. Incense Cedar at Silvercrest Picnic Area estimated to be 400 years old. |

Fig. 36. Old Incense cedar tree in the Silvercrest Picnic Area.

|

Fig. 37. Incense Cedar, Silvercrest Picnic Area. |

Fig. 38. Ancestral Indian-carved morteros in granite at the Silvercrest Picnic Area. |

Fig. 39. A picnic area grill next to a granite outcrop with morteros. |

Fig. 40. Indian-carved morteros in granite at the Silvercrest Picnic Area. |

Fig. 41. Indian morteros holes carved in a granite-gneiss outcrop near the picnic area. |

Fig. 42. Valley overlook looking south near the Silvercrest Picnic Area. |

|

A7

Doane Valley Area In Palomar Mountain State Park

Doane Valley is host to broad meadows on a floodplain between forested slopes in the highlands of Palomar Mountain. Upper Doane Valley is about 5,000 feet in elevation. As a result, the area is host to a unique climate and plant community. Palomar Mountain averages about 30.2 inches of rainfall each year (with an average annual snowfall of 26 inches). About 90% of the precipitation occurs between November and April. The average annual high temperature is 65ºF, the average annual low is 47ºF. Daily highs in the summer range 70º to low 80sºF, winter lows 35º to low 40sºF.

Figures 43 to 60 is a gallery of images that illustrates the scenic landscapes in Doane Valley. These were taken along a 1.5 mile loop walk that goes out along the Upper Doane Valley Trail and returns along the Thunder Spring Trail to the parking area near Doane Pond; (the pond is a popular tourist destination in the park). The trails are show on the park map (Figure 30). Doane Creek flows through the meadows and forest in upper Doane Valley into Doane Pond. Doane Creek is a tributary of Pauma Creek that drains through Pauma Valley All the local streams are part of the San Luis Rey River watershed.

The Friends of Palomar Mountain State Park provide a guide to the Doane Valley Nature Trail that links to the Doane Valley Campground. The San Diego City Schools operates the Palomar Outdoor School in Doane Valley for 6th grade outdoor education. |

Fig. 43. Thunder Spring drains into the Doane Creek. |

Fig. 44. Doane Creek, a spring fed creek flows year round. |

Fig. 45. Cat tails along the shore of Doane Pond. |

Fig. 46. Doane Pond at the west end of the Doane Valley. |

Fig. 47. Large oak with picnic table near Doane Pond. |

Fig. 48. Meadow along the Upper Doane Valley Trail. |

Fig. 49. Meadow along the Upper Doane Valley Trail. |

Fig. 50. Meadow view along the Upper Doane Valley Trail. |

Fig. 51. Meadow view along the Upper Doane Valley Trail. |

Fig. 52. Old live oak trees in Doane Creek valley. |

Fig. 53. Forest along the Thunder Spring Trail. |

Fig. 54. Forested slope along the Thunder Spring Trail. |

Fig. 55. Bracken ferns along the Thunder Spring Trail. |

Fig. 56. Rocky stretch of the Thunder Spring Trail. |

Fig. 57. Bracken ferns along the Thunder Spring Trail. |

Fig. 58. Meadow view along the Thunder Spring Trail. |

Fig. 59. Meadow view along the Thunder Spring Trail. |

|

Fig. 60. Panoramic view of the forested hill slope along the Thunder Springs Trail along the south side of Doane Valley.

|

A7

Boulders and Trees In the Cedar Grove Group Campground Area (Palomar Mountain State Park)

The Cedar Grove Group Campground area is a delightful area to camp and explore with its unusual boulder areas and large trees.

It is an interesting area to see how trees adapt to the rocky landscape and contribute in the weathering process of splitting rocks where roots grow into fractures and expand (Figures 61 to 68). |

Fig. 61. Oak with spreading branches surrounded by picnic tables. |

Fig. 62. Campsite grill among boulders in a campsite.

|

Fig. 63. Fractures define the shape of boulders in the campground area. |

Fig. 64. Boulders in the campground area.

|

Fig. 65. Trees growing between boulders in the campground area. |

Fig. 66. Massive oak tree roots spreading over an outcrop for support. |

Fig. 67. Trees growing between boulders in the campground area. |

Fig. 68. Looking up at the canopy of a large oak tree.

|

|

A8

East Grade Road to Henshaw Valley

The drive along East Grade Road on Palomar Mountain is well worth the time and effort to include multiple stops at overlooks along the way. Three developed overlooks along the East Grade Rode provide views of region around Palomar Mountain. The Kica Mik Overlook is about a mile west of the intersection with South Grade Road (Figure 69). The Gregory Pacheco Firefighters Memorial overlook is about 2 miles west of the intersection. Many of the outcrop and fault valley pictures shown above were taken along the West Grade Road. There are additional pull offs along the side, but be cautious when stopping along the road because of speeding vehicles with distracted drivers. Also, the gravel along the side of the road may be soft, and the slopes next to the road are very steep. Figures

70 to 73 show view from the Henshaw Scenic Vista area. (See overlook locations on the maps above.) |

Fig. 69. Kica Mik Overlook area along the Wes Grade Road. |

Fig. 70. California poppies blanketing fields in Henshaw Valley. |

Fig. 71. California poppies blanketing fields in Henshaw Valley. |

Fig. 72. California poppies blanketing fields in Henshaw Valley. |

Fig. 74. California poppies blanketing fields in Henshaw Valley. |

|

Fig. 74. Panoramic view to the east from the Henshaw Scenic Overlook on West Grade Road.

|

A9

Palomar Mountain After Dark

The Palomar Observatory is owned and operated by CalTech and is home to three active research telescopes: the 200-inch (5.1-meter) Hale Telescope, the 48-inch (1.2-meter) Samuel Oschin Telescope, and the 60-inch (1.5-meter) telescope. Research at Palomar Observatory is pursued by a community of astronomers from Caltech and other domestic and international partner institutions. The Observatory Center (community and facilities) includes a visitor center that has museum displays that highlight current major knowledge in astronomy. It is recommended to check the Visiting Palomar Observatory website before attempting to go to the observatory.

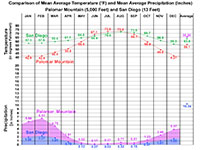

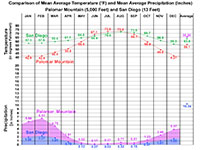

Although the Observatory is closed at night, on clear night s dozens of people gather for monthly "star parties" held at U.S. Forest Service's Observatory Campground (fee area) on Palomar Mountain. Amateur astronomers provide telescopes. These "Explore the Stars" events are held one weekend a month from April through October. Figure 82 shows the monthly average temperature and precipitation totals for Palomar Mountain that might be useful for planning at trip to the mountain. |

Fig. 75. A sequoia tree at the Palomar Observatory Museum. |

Fig. 76. Path to the historic Palomar Observatory.

|

Fig. 77. Cirrus cloud behind the Palomar Observatory.

|

Fig. 78. View looking north from near the high point on Palomar Mountain.

|

Fig. 79. Sunset from an overlook on West Grade Road on Palomar Mountain. |

Fig. 80. Sunlight reflected off the Pacific Ocean as seen from Palomar Mountain. |

Fig. 81. Zoom view of a sunset on the Pacific Ocean from Palomar Mountain. |

|

A10

Selected Resources

Cleveland National Forest (US Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service) website. (link)

Palomar Mountain State Park (official website). (link)

Friends of Palomar Mountain State Park. (link)

Palomar Observatory (CalTech website). (link)

Palomar Mountain (PAMC1) weather station (National Weather Service). (link)

Geologic Map of California: Caifornia Department of Conservation, California Geological Survey and U.S. Geological Survey. (link)

Treiman, J.A., compiler, 1998, Fault number 126d, Elsinore fault zone, Temecula section, in Quaternary fault and fold database of the United States: U.S. Geological Survey website (as of 04/28/2021). (link) |

Climate Data

Fig. 82. Comparison of mean monthly and annual average temperature (°F) and mean average precipitation (inches) for Palomar Mountain (5,000 Feet) and San Diego (13 Feet) (Airport) - U.S. National Weather Service data, 2020. |

https://gotbooks.miracosta.edu/fieldtrips/palomar_mountain/index.html

|

5/14/2021 |

|