Wilderness Gardens County Preserve |

|

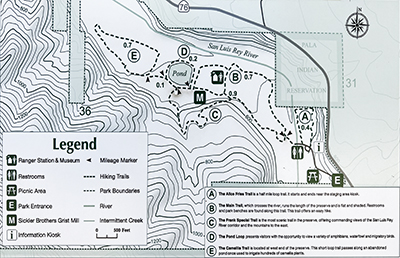

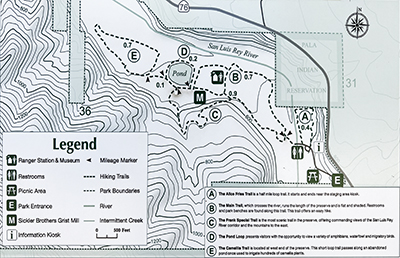

Wilderness Gardens County Preserve is located at 14209 Highway 76 several miles south of Pala in the northern part of San Diego County. Hours are 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., Thursday – Tuesday; Closed Wednesdays (and Christmas) Pedestrian access is available from sunrise to sunset, daily. Day-use parking is $3. The park offers more than 4 miles of relatively easy hiking trails and picnic area (see map, Figure 1).

This 737 acre open space preserve is located in the San Luis Rey River watershed and encompasses floodplain and lower hillslope habitats in the valley on the south side of Agua Tibia and nearby Palomar Mountain. The preserve is the oldest open space preserve in San Diego County (established in 1973) and is a destination ideal for birding, wildlife, wildflower viewing, and casual day hiking (Figures 2 to 5).

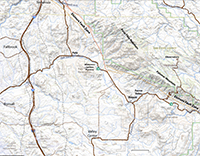

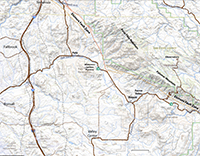

Figures 6 and 7 are topographic maps that show the location of the preserve (at different scales). Figure 8 is a satellite map and Figure 9 is a geologic map of the vicinity. Note that the geologic feature of perhaps greatest significance in the region is the Elsinore Fault, an active earthquake fault that is essentially responsible for shaping the regional landscape. The fault trace runs nearby, along the southside of the valley on the flanks of Palomar and Agua Tibia Mountains. |

Click on images for a larger view. |

Fig. 1. Trail map of the Wilderness Gardens Preserve.

|

Fig. 2. Sign on Highway 76 at the entrance to Wilderness Gardens Preserve. |

Fig. 3. Kiosk displays park rules, trail map, and wildlife information in the preserve. |

Fig. 4. View of the San Luis Rey River valley in the Wilderness Gardens Preserve. |

Fig. 5. View of Agua Tibia Mountain north of the preserve area. |

Fig. 6. Regional topographic map around the preserve. |

Fig. 7. Regional land-use map around the preserve. |

Fig. 8. Regional satellite map around the preserve. |

Fig. 9. Regional geologic map around the preserve. |

|

Geologic Setting

Figure 10 shows the dry stream crossing of the San Luis Rey River near the parking area (note the depth markers on the cement wall). This San Luis Rey River is an ephemeral mountain stream, flowing on the surface only during wet seasons and after storms. Figure 11 shows clearwater flow when the stream is being fed by groundwater from the shallow aquifer below the floodplain. Some of the floods in this mountainous watershed can be intense and potentially catastrophic. The numerous massive boulders scattered across the floodplain are a testament to the power of the episodic floodwaters.

Based on the geologic map (see Figure 9), the bedrock geology of the preserve is granitic rocks associated with the Peninsular Ranges Batholith that forms the crystalline core of the mountain ranges in San Diego County and beyond in Southern California. The batholith is an assemblage of numerous igneous intrusions that formed in association an ancient volcanic arc that existed across the coastal region during the Cretaceous Period (between about 120 to 93 million years ago). These ancient igneous intrusive bodies cooled to form the crystalline granitic rocks (mostly tonalite and gabbro varieties); the bedrock that locally crop out on the moutainsides. These rocks also make up most of the boulders visible in the stream bed and scattered across the floodplain. They are also well exposed in the cliff on the north side of the stream valley (along the Alice Fries Trail). The boulders exposed in the cliff are part of an older alluvial fan that once filled the valley to a higher level. Most of the white stream boulders are tonalite (in composition), some of the scattered darker boulders are gabbro. Other boulders consist of foliated schist and gneiss that were transported in from sources upstream (an example is Figure 16). This darker metamorphic rock are remants of even older ancient rocks that predate the Peninsular Ranges Batholith. These boulders share similarities with rocks associated with the Julian Schist, a belt of ancient ocean crustal metamorphic rocks of Triassic-Jurassic age, named for exposures in the vicinity of Julian, CA.

|

Fig. 10. Stream crossing with water depth markings on wall near the Staging Area Kiosk. |

Fig. 11. Looking upstream with the forested canyon wall in distance. |

Fig. 12. Ripple bedding glistens with mica flakes after floodwaters recede. |

Fig. 13. Large boulders blanket the broad floodplain of the San Luis Rey River. |

Fig. 14. Granite boulders in the dry river bed.

|

Fig. 15. Large boulders in the stream bed are a testament of the power of occasional floods.

|

Fig. 16. A river boulder displaying crenulated bands of biotite schist.

|

Fig. 17. Zoom view of the tourmaline gem mines on Agua Tibia Mountain, west of the preserve near Pala. |

|

Trails

There are several miles of interconnect trails throughout the preserve. Some are used by park maintenance vehicular activity, others are hiking trails. (See Figure 1.)

The Alice Fries Trail is a half-mile easy loop trail that starts at the Staging Area Kiosk near the parking area (Figure 18 to 20. It follows the north bank of the San Luis Rey River stream channel and loops around the floodplain area beneath the boulder covered cliff face before returning the the kiosk. The San Luis Rey River is dry most of the year, but occasionally experiences significant floods during winter wet seasons and summer monsoons. The river has carved down through an old alluvial van, creating the massive cliff wall of poorly consolidated sediments that borders the north wall of the canyon.

The Main Trail is an wide, flat, unpaved trail that runs the length of the preserve. It connects with the Pond Loop Trail , a shaded, flat path that locally provides views of the marsh and ponds that are host to waterfowl and migratory birds. One of the two ponds stays flooded year round and is host to a thriving population of non-native bullfrogs that provide quite a chorus in warm weather.

An unnamed trail on runs along the south side of the valley. This "Southside Trail" is narrow trail runs along the south side of the valley and connects with the Frank Special Trail that climbs partway up the hillsides on the south side of the valley. This trailproviding scenic views of the river cooridor and the mountains on the northeast side of the valley.

The Camelllia Trail is a short, flat loop trail along an abandoned pond at the west end of the preserve. |

Fig. 18. Staging Area Kiosk near the parking area at the Alice Fries Trailhead. |

Fig. 19. Alice Fries Trail is an easy 1/2 mile walk on the floodplain. |

Fig. 20. An oak tree provides good scale to the boulders in the old alluvial fan deposits. |

Fig. 21. Park benches are found ins shady spot along the trails near the ponds area. |

Fig. 22. Boulders on and along the Southside Trail.

|

Fig. 23. Trail along the abandoned channel that fed water to the mill. |

Fig. 24. View along the Southside Trail.

|

Fig. 25. Trail on the floodplain at the west end of the preserve.

|

|

Archeology and History

The establishment of the Wilderness Gardens County Preserve in 1973 is a milestone in the growing conservation movement to protect and restore native habitats in the region (Figure 26). Morteros (grinding holes) can be found on boulders scattered throughout the San Luis Rey valley (Figure 27). These grinding stones are a testament to hundreds to thousands of years of use by ancestral native populations (the Luiseño Indians) that lived and migrated through here, leading up to the modern tribes still utilizing the valley and region.

The historic Sickler's Grist Mill (now only a foundation) is part of pioneering story in the valley when ranching and agriculture utilized the preserve area in the late 19th century. Agricultural activity continued into the mid 20th century. Information about the local history is presented in the preserve's visitor center at the ranger station. |

Fig. 26. Plaque dedicating establishment of Wilderness Gardens on a large granite boulder. |

Fig. 27. Indian mortar hole on a granite boulder.

|

Fig. 28. Historic Sickler's grist mill.

|

Fig. 29. Historic mill waterwheel on display next to millhouse ruins.

|

|

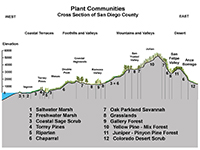

Ecosystem, Plants & Animals

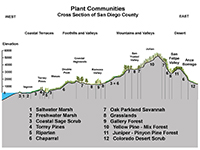

The San Luis Rey River valley and mountains surrounding the Wilderness Gardens Preserve host a variety of plant communities and wildlife habitats (Figure 30). The floodplain of the San Luis Rey River valley is host to a mix of restored riparian, grassland, and oak woodlands on land that was previously heavily used for agriculture and grazing, and occasional scorched by wildfire. Chaparral and coastal sage dominate the mountain slopes on both sides of the valley. Ponds once used for agriculture are still maintained to support wildlife habitat for birds and other wildlife. Coyote, mule deer, racoons, bobcat, and rattlesnakes are not uncommon sightings in the preserve. |

Fig. 30. Plant communities cross section of San Diego County.

|

Fig. 31. Chaparral plant community dominates the north-facing mountain slope of the south side of the preserve. |

Fig. 32. Poppies bloom in the grasslands dominate the dryer south-facing slopes north of the preserve. |

Fig. 33. A mixed oak woodlands, coastal sage, and grassland community covers the valley floodplain. |

Fig. 34. Mixed coastal sage and oak woodlands habitat on the floodplain.

|

Fig. 35. Grasses dominate areas of the drier well-drained soils of the floodplain.

|

Fig. 36. Drought tolerant oak on the floodplain.

|

Fig. 37. "Leaves of 3, let it be." Poison oak is common along the trails, along with other "hostile vegetables. |

Fig. 38. Man-made marsh/pond on the floodplain.

|

Fig. 39. View of the pond and marsh grass, and a cottonwood tree. |

Fig. 40. Shore of the pond with line of trees and cliff in distance. |

Fig. 41. Coots and other migratory waterfowl use the pond. |

Fig. 42. Bullfrog among the cattails. |

Fig. 43. Rabbit sitting alert on the trail. |

Fig. 44. Opossum climbing a small tree. |

Fig. 45. Snake trail crossing the path. |

|

https://gotbooks.miracosta.edu/fieldtrips/Wilderness_Gardens/index.html

|

3/12/2024 |

|