Chapter 9 - Weathering, Erosion, and Mass Wasting |

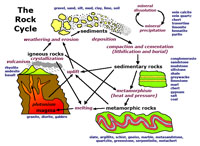

| The rocky surface of the planet is subjected to processes that break down rocks and move materials. This chapter focuses focuses on the weathering and erosion of rocks to form sediments, and the transport and modification of sediments to sites of deposition. Weathering and erosion impact the surface of the land in many way. Much of this relates to the mechanical, chemical, and biological processes breaking down rocks while shaping the landscape, including the formation of soils. Gravity has a large role in moving material downhill in a variety of means called mass wasting. Mass wasting is associated with a variety of serious landslide hazards that are often associated with heavy precipitation. Landslides can take place slowly or rapidly, and intermittently (such as events associated with seasonal storm floods or some that are triggered by earthquakes or human activities). |

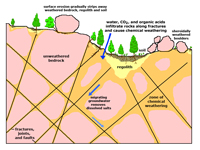

Chemical Reactions Involved In WeatheringChemical weathering involves a variety of chemical reactions including hydrolysis, hydration, oxidation, and carbonation.* Hydrolysis is the chemical breakdown of a compound due to reaction with water. * Hydration is the process of combining with water to a molecule. * Oxidation is the process of combining elements with oxygen ions. A mineral that is exposed to air may undergo oxidation. * Carbonation is saturation with carbon dioxide (as soda water). Decaying organic matter releases carbonation and organic acids that enhance the chemical reactivity between rocks and groundwater. All these chemical processes are happening around us. Weathering and erosion are continuous processes in the surface environment, enhanced by the presence of water (the "universal solvent"). In addition, barometric changes in air pressure with passing storm fronts push in or pull out air from the ground. |

What happens to common igneous rocks (granite and basalt) when they weather?Granite is common in mountainous regions in many regions in the western United States. When granite weathers, it separates into components. Mechanical weathering forces split the rock into fragments, and the interactions of water and gases slowly chemically alter some of the minerals into clay. The quartz in granite is most resistant to weathering, and remains virtually unchanged, becoming mostly gravel, sand, and silt. In contrast, the feldspars and micas eventually break down to become clays. Mafic minerals in granite break down into clays and iron-oxide residues (hematite and limonite). Soluble components dissolve and are carried away by groundwater or surface waters, eventually contributing to the salts in seawater.Basalt and most volcanic rocks of mafic and intermediate composition experiences a different fate than granite. Because basalt and these volcanic rocks are dominated by fine grained mafic minerals and feldspars, both of which break down to become clays. Sediments deposited along streams valleys and sediments deposited offshore of volcanic regions are generally dominated by mud (iron mineral residues, silt, and clay) and dissolved fractions contribute salts to seawater. |

Effects Of Physical and Chemical Conditions On Weathering

|

Factors That Influence Weathering

|

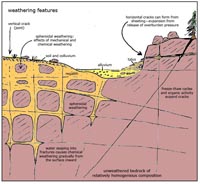

Weathering In the Subsurface, and the Origin of Rounded Boulders On the LandscapeRounded boulders are often seen on landscapes in arid regions (this is particularly well illustrated in the mountainous landscapes in Southern California). Boulders, or piles of boulders, on the landscape accumulate where chemical weathering has selectively broken down materials in the vicinity of fractures or around materials that are more durable and can withstand rock-water-air chemical weathering reactions (Figure 9-15). As a result more durable materials or the unfractured cores of large subterranean blocks may survive both chemical and mechanical weathering, where the intervening material is stripped away by erosion. Over time, erosion strips away the weathered material (soil and sediment) leaving the boulders, or piles of boulders, reposed on the landscape. Figures 9-16 to 9-18 illustrate how spheroidal weathering takes place, both below ground and above the surface. In most cases, spheroidally rounded boulders scattered on a landscape may not have moved far from their place of origin. Spheroidally rounded boulder piles on the surface exist where all the loose, weathered materials (decayed rock and soil) around the remaining boulders have been stripped away by erosion over time. Chemical weathering degrades rocks like granite to form a friable, crumbling rock residue called saprolite—degraded rock that has been sapped of its soluble components (illustrated in Figure 9-17). |

||||

|

Tafoni, An Unusual Form Of Surface WeatheringTafoni is small, fist- to head-sized, cave-like features found in granular rocks such as sandstone, granite, and other kinds of rocks. It appears as tiny pits, rounded entrances and smooth concave walls. Tafoni usually is found cliff faces, in overhanging vertical places, on large boulders, and rocky outcrops on hillsides, along canyons, and along coastlines (Figures 9-19 to 9-22). Tafoni features often occur in groups, forming a honeycomb-like form. In some locations, taphoni weathering can create cavernous pits or hollowed out boulders.How tafoni forms: Tafoni forms when rainwater or spray from seawater soaks into a porous rock and particularly dissolves mineral cements that hold mineral grains together. When drying takes place, the water trapped in the porous rock carries the dissolved mineral component back to the surface where evaporation causes the mineral component to precipitate. This precipitation of minerals (including salts or silica) creates case-harden surfaces that are more durable that the softer leached rock below the surface. Over time, the softer, leached material erodes leaving the case-hardened material behind, creating the unusual irregular tafoni weathering pattern. |

||||

|

Regolith, Colluvium, Eluvium, and AlluviumRegolith is the name for a layer of loose rock debris produced by weathering located between the bedrock and the surface in most places. Regolith can become soil with the introduction of organic residues and ongoing weathering. Once rock weather into sediments they can begin to move.Colluvium is a general term applied to loose and incoherent surficial deposits, usually at the base of a slope and brought their chiefly by gravity. Eluvium or eluvial deposits are accumulations of weathered rock fragments and soils that are derived by in-situ weathering (particularly leaching of soluble materials) or weathering plus gravitational movement and accumulation. The process of removal of materials from geological or soil horizons is called eluviation or leaching. Alluvium is a general term for unconsolidated sediments deposited by flowing water, such as on stream channel beds, flood plains, and alluvial fans (discussed in the Deserts chapter). The term, alluvium (or alluvial deposits), applies to stream deposits of recent times and it does not include sub-aqueous deposits, such as in lakes or undersea. On many geologic maps, anything that is an accumulation of sediments on land is called alluvium. However, there are sediment deposits on the surface that are not alluvium (sediments that accumulated not by flowing water alone). |

Erosion |

||

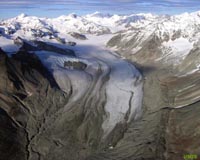

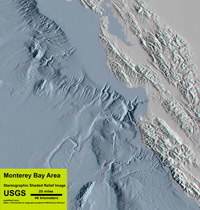

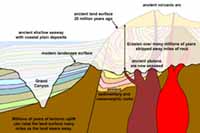

| Erosion is the mechanical processes of wearing or grinding away materials on a landscape by the action of wind, flowing water, or glacial ice. Erosion also involves the down-slope movement of materials under the influence of gravity, involving processes called mass wasting (discussed below). Erosion rates vary greatly from region to region based on climate factors, weather patterns, and bedrock conditions. Erosion produces sediments (rock particles or fragments of many sizes). In contrast, deposition is the process of sediments settling and accumulating from a moving fluid (wind, water, or ice). Chemical and mechanical weathering breaks down rocks, whereas erosion is the removal and transport of sediments to sites of deposition (deposition of sediments in sedimentary environments is discussed in Chapter 10). The migration of sediments from upland regions to the ocean basins can take a very long time. Sediments can eroded and re-deposited many times along the journey. All locations on Earth's solid surfaces are subject to erosion, this includes on land and beneath the oceans. Figure 9-23 shows the rugged landscape, coastline, and bathymetry of California's central coast. Note that Monterey Canyon offshore of Monterey Bay is nearly twice as deep as the Grand Canyon! It was carved by submarine erosion processes. When the geologist/explorer John Wesley Powell traveled west before his first legendary voyage down the Grand Canyon in 1869, he observed the highly eroded nature of the western landscapes in the Colorado Plateau region. He described it as the great denudation. The landscapes throughout the western United States shows evidence of a long history of erosion, with what appears that miles of rock have been eroded away (Figures 9-24 to 9-26). Today, a general consensus among geologists suggest that the Grand Canyon began to form about 5 to 6 million years ago as the Colorado River began to carve the canyon as the Kaibab Plateau began to rise. The canyon is now about a mile deep (Figure 9-25). In many locations, mountain ranges erode nearly as fast as as they are uplifted along faults or as volcanoes form. For instance, in many locations in California's Sierra Nevada Range and SoCal's Peninsular Ranges, the ancient plutons that were once possibly miles below volcanoes of an ancient volcanic arc 70 to 90 million years ago are now exposed as eroded remnants on the landscape. Figure 9-26 shows the eroded roots of a volcanic arc region in the City of Rocks National Preserve in Idaho. Streams channels act as the main location of erosion on a landscape. The steeper the stream gradient, the more sediments are eroded and transported. Waves energy is a persistent force of erosion along coastlines, carving away exposed bedrock and generating currents that move sediments to sites of deposition offshore (Figure 9-27). Human activity has become a dominant force of erosion in many parts of the world. In some places, mining operations, constructions of highways, and construction in urban areas have moved more materials than natural erosion has moved in millions of years (Figure 9-28). |

Fig. 9-23. Erosion takes place both on land and on the seabed.  Fig. 9-25. The Colorado River has eroded away a mile of rock where it crosses the Kaibab Plateau in the Grand Canyon. Fig. 9-25. The Colorado River has eroded away a mile of rock where it crosses the Kaibab Plateau in the Grand Canyon. Fig. 9-27. Wave erosion is persistent, causing significant erosion and generating massive amounts of sediment. |

Fig. 9-24. The modern landscape in many regions is the eroded remnants of ancient landscapes and landforms.  Fig 9-26. Oval-shaped plutons of granite in City of Rocks National Preserve, Idaho are all that remain of an ancient volcanic arc that eroded away long ago.  Fig. 9-28. Human activity is now moving vast amounts of earth materials, more than natural processes of erosion in many regions. This is a silver mine in Nevada. |

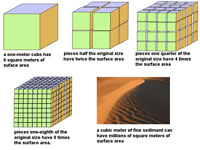

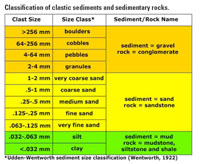

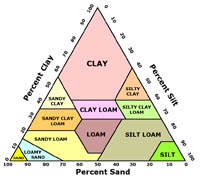

SedimentsSediments are solid fragments of inorganic or organic material that come from the weathering of rock and soil erosion, and are carried and deposited by wind, water, or ice. Sediments range in size from large blocks to microscopic particles. Figure 9-29 shows the technical definition of sediment particles (rock fragments). However, general usage is as follows ranging from largest to smallest: boulders, cobbles, gravel, sand, silt, and clays (Figures 9-30 to 9-33).Sediments form from the disintegration of rocks. They are transported, mostly by water, and in the process the fragments are abraded, with sharp edges worn down and the overall shape of particles increasing in roundness. Sediments derived from erosion on land are called lithogenous sediments. Sediments can also form from biological activity. Living organism (both plants and animals) generate the skeletal remains and residues that accumulate as biogenous sediments. Sediments are discussed in more detail in Chapter 10 - Sedimentary Rocks. Sediments that form and/or accumulate in the marine environment are discussed in detail in Chapter 15 - Ocean Basins. |

Fig. 9-29. Classification of sediments based on particle size. |

||||

|

|||||

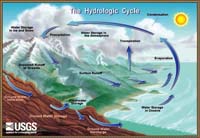

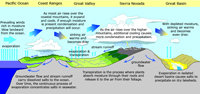

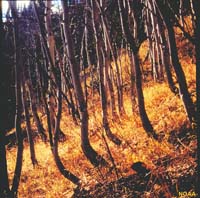

Environmental Factors That Control the Rate Of Weathering and Formation of SoilsEnvironmental factors include:• climate (water availability and temperature effects) • macro- and microorganisms living in or on the soil • erosion rates • duration of exposure to air and water. Climate is perhaps the most significant factor in soil formation and soil character. Climate is the general weather conditions prevailing in an area or region, and may reflect seasonal variations related to temperature and precipitation. Figure 9-34 illustrates the Hydrologic Cycle, the movement of water through the physical environment. California has its own unique hydrologic setting that is linked to the character of the landscape and its location along the Pacific Ocean Basin (Figure 9-35). In the coastal mountain regions and the Sierra Nevada weathering is most intense because the abundance of water (Figures 9-36 and 9-37). However, most lowland and desert regions of California are subject to long periods of no rain (even drought) when little erosion occurs. Then wet periods occur, typically in the winter, or sudden intense summer thunderstorms occur. During one of these thunderstorms, landscapes that have thin vegetation because of extended dry periods may experience tremendous erosion, removing large quantities of soil and weathered bedrock. It is the reason so many western mountainous areas are devoid of vegetation. The soil has been stripped away, so plants cannot become established. |

|||||

|

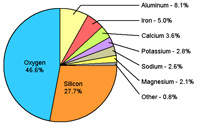

|||||

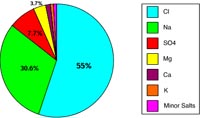

Fate of Soluble Components Of Rocks: Formation Of SeawaterAs rocks weather, they loose their soluble elemental components, they dissolve in groundwater and surface runoff and are carried away, eventually reaching the ocean, or as in the Great Basin region, end up being concentrated as salts on dry lake beds (or brine in basins such as Mono Lake (CA) or the Great Salt Lake (Utah). Over billions of years, rivers and streams, and groundwater flowing into the oceans have contributed to the saltiness of seawater. Salt in seawater is concentrated by the evaporation of water back into the atmosphere. Figures 9-38 and 9-39 show the abundance of elements in the Earth's crust compared to the elemental components of salts dissolved in seawater. |

Fig. 9-38. Composition of crustal rocks, some elements are more soluble and others. |

Fig. 9-39 Elemental components of salts dissolved in seawater. |

SoilsIn most places, soil is the upper layer of Earth composed of unconsolidated materials in which plants grow. Soil contains organic matter (remains of plant, animal, and microbial matter) mixed with mineral matter and rock fragments derived from weathering and erosion. Soil also contains open voids that contain water and gases. Soil may also contain live plants, microbial life forms, and contain plant or animal remains that may or may not have begun to decompose.The content of soil reflects many environmental factors including climate (seasonal water availability and temperature effects), relief (flat vs. slopes), and biological activity (microorganisms, plants, and burrowing animals). The character of soils is also dependent on the chemical and physical characteristics of the source material (weathered rocks and sediment), and how all these factors interact over time. Soil is typically a black or dark brown color, but can be many shades of yellow, orange, red, or gray, depending on its principle mineral and organic components (examples: organics tend to be black to brown, hematite is brown, calcite, quartz sand or clay-rich sediments tend to be yellow, white, or gray.

|

Fig. 9-40. Components of soil  Fig. 9-41. Examples of types of soil from California . Dark soils are rich in organic matter; brown and red soils are enriched in iron; light colored soils are enriched in clays, quartz silts and sand, and calcite.  Fig. 9-42. The types of soils in a region can vary considerable depending on many environmental factors.  Fig. 9-43. Agricultural practices can significantly change the character and quality of soil. Long-term agricultural practices have significantly reduced to thickness and quality of soil in many areas. New methods are being devised and used to reduce soil degradation. |

The Relationship Of Soils With Plants (Example: Serpentinite Soil)Note that native plants are adapted to different, often unique, soil conditions. A region may have different kinds of soils in different settings, and may therefore host a variety of ecosystems associated with the different soils in a region. For instance, Northern California has many areas that have serpentinite bedrock (which weathers to become serpentinite soil)(Figure 9-44). Serpentinite is a rock that naturally contains high concentrations of metals (it is ultramafic, meaning enriched in iron and magnesium). However, in some places serpentinite is enriched in the elements of nickel, chrome, mercury, manganese, and other elements that are toxic to most plants. Over many thousands of years, some plant species have adapted to tolerate concentrations of these heavy metals, and therefore can survive where non-native invasive species cannot. |

Fig. 9-44. Plants adapted to serpentinite soil in the Santa Cruz Mountains, California |

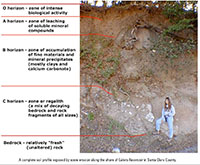

Soil Profiles: The Character of Soil Changes With DepthThe soil on the surface is typically quite different that how it appears several inches below the surface, and even more so with increasing depth to where it rests on weathered bedrock; the lower boundary of soil profile is often difficult to define. A soil profile is subdivided into soil horizons, or layers, that are distinguishable from the initial material as a result of additions and losses (transfers of fine sediment or dissolved components), and transformations in the chemistry of materials, or the ability to support rooted plants. In most places, agricultural practices have largely changed the character of soils from what might be construed as its original natural character. Figure 9-45 illustrates a soil profile with its different horizons exposed. |

|

| O horizon—zone of intense biological activity, interval with the accumulation of organic residues (humus). A horizon—zone of leaching of soluble mineral components. B horizon—zone of accumulation of fine materials and mineral precipitates (mostly clays and calcium carbonate). C horizon—zone of regolith (a mix of decaying bedrock and rock fragments of all sizes). bedrock—relatively fresh, unaltered solid (consolidated) rock below the surface or exposed in rocky outcrops. |

Fig. 9-45. Example of a soil profile exposed by erosion along a stream bed. |

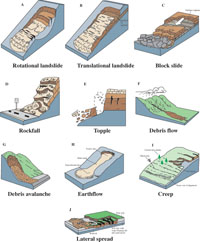

Mass WastingMass wasting is a general name for processes by which soil, regolith, and rock move downslope under the force of gravity. Types of mass wasting include landslides, mudflows, debris flows, lahars, topples, rock falls, and avalanches, and creep—each with its own geomorphic characteristics, and taking place over time scales ranging from seconds to years. It does not include surface erosion by running water, however, streams in flood can in some cases carry as much sediment as the water moving downstream. It may be caused by natural erosional processes, by natural disturbances, or by human disturbances.Landslide is a general term covering a wide variety of mass-movement landforms and processes involving the down slope transport of soil and rock under the influence of gravity. Usually the displaced material moves over a relatively confined zone or surface of shear. Landslides have a great range of morphologies, rates, patterns of movement, and scale. Their occurrence reflects bedrock and soil characteristics and material properties affecting resistance to shear. Landslides are usually preceded, accompanied, and followed by perceptible creep along the surface of sliding and (or) within the slide mass. Slumps, debris flows, rock falls, avalanches, and mudflows are all forms of landslides. Each type has own geomorphic characteristics, and taking place over times scales ranging from seconds to years. Types of mass wasting include: * rock falls and topples * slides (rockslide & mudslides) * debris flows and floods (including lahars on volcanoes) * avalanches * creep Landslides can be extremely hazardous. Estimates vary, but current thought is that thousands to tens-of-thousands are killed by landslides each year, most often in association with storms in mountainous terrain, and areas of poor land-use planning and building codes. Most deaths occur in Southeast Asia. Landslides associated with large volcanic eruptions can do even greater damage. Damage by "landsliding" causes billions of dollars in damage each year, affecting homes, buildings, roads, bridges, and all kinds of infrastructure. Much of the damage is a result of minor shifts in the soil beneath poorly or improperly-designed foundations. Some regions are more likely to experience landsliding, and it is related to the character of the bedrock and soil, the relief of the land, and the amount a rainfall received in an area. Geologists and engineers classify landslide-prone areas. They use the word susceptibility—defined as the state or fact of being likely or liable to be influenced or harmed by a particular thing. In geology, the term is used as a means of classifying areas that are prone to natural hazards, such as landsliding, liquefaction, flooding, fire, avalanches, etc. Home buyers should really know the risks of landsliding in an area before purchasing! |

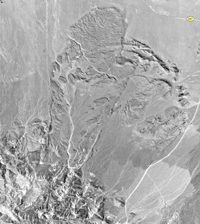

Landslide HazardsLandslides can be massive and sudden events, or slow moving disasters. Landslides are largely unpredictable. They can stall or move very slowly for long periods, then change suddenly and move catastrophically. Landslides prone areas often display evidence of the kinds of landslides that have occurred in the past. Whole mountainsides may be covered with a large "landslide complex" where some parts are dormant, and other are active. Sadly, whole communities have been builds on large landslide complexes, particularly along coastal areas or mountain communities near cities where land for development is scarce, and often in the past real estate developers have simply bulldozed over landslide features before building communities. It may be many years before homeowners realize their mistakes of purchasing a home in a landslide-prone area.California's Blackhawk Landslide is one of the largest known landslides in North America (Figure 9-46). It is located in Lucerne Valley (east of LA). Blackhawk slide is 5 miles long, about 2 miles wide, and 30-100 feet thick. The landslide occurred in prehistoric times, but is well preserved because of the dry climate. It serves as a grim reminder about the uncertainty of living in landslide-prone areas. |

Fig. 9-46. Aerial view of the Blackhawk Landslide, one of the largest in North America |

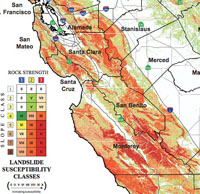

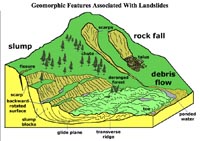

Landslide SusceptibilitySome hilly and mountainous regions are more prone to landsliding than others. Areas with steep slopes, certain kinds of soils or sediment cover, ore areas undercut by stream erosion are more likely to experience landsliding. It is usually possible to see evidence of past and or current landsliding in susceptible areas. Figures 9-47 and 9-48 illustrate landslide susceptibility maps for California. The term landslide applies to include many kinds of landscape features associated with mass wasting.Figures 9-49 to 9-50 illustrate common landscape features and processes associated with landsliding. |

|||||

|

|||||

Example of Landslides IllustratedRock fall—the relatively free falling or precipitous movement of a newly detached segment of bedrock of any size from a cliff or very steep slope (Figure 9-51). Rock falls are most frequent in mountainous areas during spring when there is repeated freezing and thawing of water in cracks in rock. Movement may be straight down or in a series of leaps and bounds down the slope; it is not guided by an underlying slip surface (like a slump).Talus—a sloping mass or cone-shaped deposit of rock fragments (often loose or slightly compacted) at the foot of a cliff (Figure 9-52). The angle of repose is the steepest angle of descent or dip of the slope relative to the horizontal plane when material on the slope face is on the verge of sliding. Talus slopes reflect the angle of repose of coarse sediments. Rock slide—the usually rapid downslope movement of newly detached segments of bedrock. Rock slides can be small to extremely large, moving whole mountainsides and filling in valleys, damming rivers (Figure 9-53). Avalanche—a mass of snow, ice, rocks, and debris falling rapidly down a mountainside (Figure 9-54). |

| Slump—a type of landslide where the downward slipping mass of unconsolidated material or rock moves as a unit (Figure 9-55). A slump block usually displays backward rotation and on a more or less horizontal axis parallel to the slope or cliff from which it descends. Slumps often reveal themselves by trees leaning in odd directions (called a "drunken forest" or "deranged forest"), and lumpy terrain at the toe where broken-up material is pushed up. Springs commonly are found in the vicinity of the toe of a slump. Slumps typically have a fault-like escarpment at the head of a landslide (Figures 9-56 to 9-59). Earth flow—a slow moving downslope viscous flow of fine grained materials that have been saturated with water, and moves under the pull of gravity; a slow moving mass of material, slower than a more fluids debris flow, rock fall, or avalanche (Figure 9-60). Debris flow—a moving mass of rock fragments, soil, and mud in which more than half of the particles being larger than sand size (otherwise it would be a mudflow) and with 70 to 90 percent of the material consisting of sediment (the rest is water and trapped gases). Slow debris flows may only move a few feet per year, whereas rapid ones can reach speeds greater than 100 miles per hour. Debris flows can display either turbulent or laminar flow characteristics. Debris flows can travel long distances down into valley regions (Figure 9-61). Debris flows associated with volcanoes are called lahars, and have a history of wiping out whole villages and communities where they are known to happen. Mudflow—a downhill movement of soft wet mud and rock debris, made fluid by rain or melted snow, and capable of moving downslope at great speed (also see debris flow). Debris flood—a typically disastrous flood, intermediate between the turbid flood of a mountain stream and a debris flow, ranging in sediment load between 40 to 70 percent (the rest is water and trapped gases)(Figure 9-62). Many streams in the American West are prone to debris floods, worthy of the old phrase about rivers in the western United States: "Too thick to drink, too thin to plow!" |

||||||||

|

Lahars: Landslides in Volcanic RegionsLandslides in volcanic regions are particularly dangerous, particularly on volcanoes that are composed of massive amounts of ash, cinders, and other debris. A pyroclastic flow is a dense, destructive mass of very hot ash, lava fragments, and gases ejected explosively from a volcano and typically flowing downslope at great speed. A nuée ardente is an incandescent cloud of gas, ash, and lava fragments ejected from a volcano, typically as part of a pyroclastic flow. Just like landslides, the hot mass of gas, ash, and volcanic debris flows downslope like an avalanche, only hot and capable of burning and burying everything in its path (Figure 9-63).The heat of a volcanic eruption can suddenly melt glacial ice contributing massive amounts of water to a pyroclastic flow producing a lahar. A lahar is the term for any kind of debris flow or debris flood from a volcano. Lahars race down mountainsides and can flood stream valleys for many miles downstream, carrying with them massive amount of sediments (Figure 9-64). High volcanoes, like many in the Cascade Range in northern California, Oregon, and Washington, accumulate massive amounts of precipitation in the forms of ice, snow, and rain (Figures 9-65 to 9-66). The weigh of this precipitation can cause mountain slopes to fail. Earthquakes and volcanic eruptions can also trigger massive landslides. that can Every year in volcanic regions around the world, hundreds to even thousands of people are killed and massive damage to infrastructure as a result of lahars. Landsliding during major tropical storms in volcanic regions are particularly destructive. |

||||

|

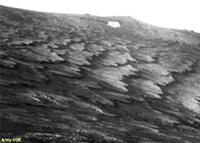

Creep and SolifluctionIn geology, the word creep has two meanings. In earthquake terminology, creep is the slow, more or less continuous movement occurring on faults due to ongoing tectonic deformation. In landslide terminology, creep is slow, more or less continuous downslope movement of surface materials (mineral, rock, and soil particles) under gravitational stresses. Figure 9-57 shows trees that have curved trunks from adjusting to the slow creep of soil down a slope.Solifluction is the slow, downhill movement of soil or other material in areas that experience freeze-thaw cycles. When water freezes in soil, ice expands moving sediments, pushing them upward or outward. As the ground warms up, the ice between sediment grains melt, allowing the sediments to sink or readjust under the influence of gravity or moving fluids (Figure 9-68). Freeze-thaw cycles are common in high elevations and in winter in mid-latitude regions where there are wide temperature ranges daily and seasonal basis. |

Fig. 9-67. Trees adjust their trunks to counter the effect of soil creep on a slope. |

Fig. 9-68. Solifluction associated with freeze-thaw cycles cause soils to move down slope, creating a step-like pattern on some slopes. |

Wildfires Can Change Landscapes In Many WaysMany parts of the United States are prone to wildfire disasters, but wildfires are a part of the natural processes that change the landscape (Figure 9-69). Wildfires create massive amounts of sediment, both as airborne dust and debris, and as material that is easily eroded by rain storms in the period after after a fire and before vegetation can grow back to help hold loose material (sediment and ash) in place. Perhaps ironically, rainstorms after fires create some of the most deadly disasters after wildfires. Without plant cover after a fire, an intense rainfall causes surface runoff to turn into massive debris flows that can cause catastrophic damage along stream valleys, even many miles away from where wildfires have burned (Figure9-72). |

||||

|

Humans Are Agents Of ErosionIt is easy to argue that humans have become a major, if not the most significant, force of erosion on the planet. Construction of cities, highways, agriculture, dams, levees, and massive mining operations for metals, construction materials, coal, and other resources are now changing the surface of the planet more rapidly that all natural landscape-changing forces combined. That is at least, in most years. Some of that construction is done to try to prevent natural catastrophes from destroying developments, often with limited success. |

Fig. 9-73. Cities (like San Francisco shown here) are constructed from vast quantities of material moved and refined from the ground. |

Fig. 9-73. Explosive blasting is one of many ways human break down large quantities of rocks in mines and construction sites. |

Fig. 9-74. Large mining operation move large quantities of rock, altering landscapes, such as this large coal strip mining operation. |

| Chapter 9 Quiz Questions |

|

| https://gotbooks.miracosta.edu/earth_science/chapter9.html | 12/28/2018 |