8. Harriman State Park

Harriman State Park was established in 1900 as part of the Palisades Interstate Park Commission. It covers 46,181 acres of forested mountainous terrain within the Hudson Highlands region in Orange and Rockland Counties, New York. The park is host to numerous bogs and lakes, and has several hundred miles of hiking trails, including almost 16 miles of the Appalachian Trail. The park adjoins Bear Mountain State Park to the east along the Hudson River. After previous, failed, attempts to preserve the parklands, Bear Mountain-Harriman State Park became a reality in 1910 thanks to the ambitious leadership and financial resources of Union Pacific Railroad president, E. W. Harriman, and the gifts of land and money by numerous wealthy businessmen.

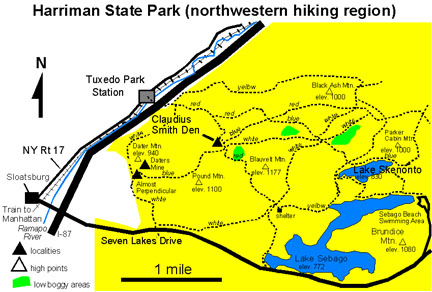

Along the western side of the park, the New York Thruway (I-87), NY Route 17, and the Metro North Train Line follow the valley of the Ramapo River. Several scenic roads that intersect NY Route 17 traverse the park, including Seven Lakes Drive which enters the western end of the park at Sloatsburg, NY. Figure 26 is a map of the trail system in the western half of the park. This section of the park contains a variety of geologic features in very scenic settings. It should be noted that several hours of moderately strenuous hiking are required to view these localities, but the scenic rewards are stupendous! In addition, Metro North stops at Tuxedo Park Station, making the hiking trails at the western end of the park accessible from the city without the need of a car! The park has an extensive system of trails that are well marked and well maintained. Exceptional trail maps are available, particularly those published by the New York/New Jersey Trail Conference, a regional hiking club (available in most camping stores).

|

| Figure 26. Trail system and investigation sites in western Harriman State Park (map modified after Palisades Interstate Park trail map). |

A trail that leads to the park starts at the southern end of the Tuxedo Park train station parking lot. It crosses a foot bridge across the Ramapo River, then follows a road through an underpass beneath the Thruway. The trail follows the road as it curves to the left and winds up a hill. A trailhead is on the right approximately a quarter mile past the underpass bridge. Once in the park there are numerous trails to choose from; all of them are moderately to fairly strenuous. Elevation gain from the river to the hilltops is over 600 feet. Plan to carry a lunch with extra water, and enjoy a long circuit hike. High areas offer spectacular views scattered among the forested peaks. Low paths offer access to tumbling brooks and lakeside settings.

The Tuxedo Park trail climbs fairly steeply up the eastern side of the Ramapo River Valley. Several very scenic overlooks approximately a mile into the trail provide vistas of the valley and glacier scoured exposures of bedrock. The rocks throughout the park are dominantly granitic and amphibolite gneiss of Middle Proterozoic age. The Ramapo River Valley is carved into the fracture zone of a large northeast-trending fault, an offshoot of the greater Ramapo Fault that borders the western margin of the Newark Basin. In this region, however, rocks on either side of the fault are both Proterozoic gneiss.

Many of the low areas are swamps or bogs which were once glacial kettles and ponds that filled with muck and organic debris over time. Such bogs in the region have been cored and examined for pollen residues to determine the progression of reforestation of the region after the ice melted. Cores reveal that after the glacial ice retreated roughly 15,000 years ago, tundra grasses and shrubs persisted for about 3000 years, and were ultimately replaced by spruce-dominated forests around 12,000 years ago. These gave way to the more modern deciduous forests beginning around 7,000 years ago. These changes in vegetation reflect the gradual warming of the climate as the glaciers retreated northward.

One of the most scenic locations within the park is named Claudius Smith Den, a small overhang beneath a massive cliff and barren hilltop consisting of granite gneiss. The hillsides around the den are host to mountain laurel that blooms starting in late May through June. Claudius Smith, "the Cowboy of the Ramapos," was an ardent Tory who, with the help of three of his sons and other outlaws, raided farms in the region to steal horses to sell to the British. The sheltered overhang was supposedly one of his hideouts. It makes a wonderful picnic stop, (especially when it is raining). The hilltop above the overhang is barren of soils, and locally preserves grooves and striations carved by rocks imbedded in glacial ice as it passed over (Figure 27). The hilltop is a large roche mountonnee, a name given to hills of glacially-scoured bedrock characterized by steep lee sides where the hill was broken away. This occurred as water seeped downward into cracks beneath the glacier and froze, causing large blocks of rock to break loose to be carried away by the flowing ice.

|

| Figure 27. View of the barren, glacier-scoured hilltop above Claudius Smith Den in Harriman State Park. The view of the hilltops in the distance illustrates the Schooley Peneplain, a mid-Tertiary erosional surface that is now the top of the regional erosionally dissected plateau. |

The barren hilltop exposure offers exceptional views in all directions. It is interesting to note that all the hilltops in the area are about the same elevation in height (roughly between 1,000 and 1,200 feet)(see Figure 27). This similarity in elevation suggests that the region is an erosionally dissected plateau. The name, Schooley Peneplain, has been applied to this upland surface, and was interpreted to be part of an extensive late-middle Tertiary erosion surface. There is still debate as to the significance of this surface. Most of the ridge crests throughout the Appalachian region correspond to this elevated erosional surface, including the tops of the Watchungs and the most of the Highlands region in New Jersey. The surface may represent the remnant of an ancient landscape that was eroded down to base level (perhaps close to sea level). Since middle Tertiary time the region has risen slowly, allowing streams to carve downward into their flood plains, with many carving ravines and canyons into the bedrock.

The rocky exposures along the trails throughout Harriman State Park consist dominantly of granite and amphibolite gneiss that are cut locally by small quartz veins, and sometimes by migmatite. Throughout the hillsides there are numerous prospect pits and several abandoned iron mines that were worked in the pre- and post-Civil War eras. There are many mines on area maps with names such as Pine Swamp Mine, Hogencamp Mine, Doodletown Mine, Daters Mine, the Nickel Mine (due to an ore with a high nickel content). The primary ore in all the mines was magnetite, a black, shiny, highly magnetic iron mineral (Fe3O4). Accessory minerals include pyrite, biotite, and hornblende. The ore deposits occur as localized hornblende gabbro veins or small intrusions within the amphibolite gneiss. The ore was processed in large rock furnaces using charcoal derived at the expense of local forests; early photographs of the area show most of the hills completely stripped of vegetation. Lime was derived from oyster shell and limestone hauled in from quarries in the surrounding region. At the climax of the iron mining industry in the early 1900s, the Highlands mining industry produced approximately 17 percent of the world's iron. The Highlands iron industry faded as Pennsylvania coal and Lake Superior iron production developed in the Great Lakes region.

| Return to the Highlands Province Main Page. |