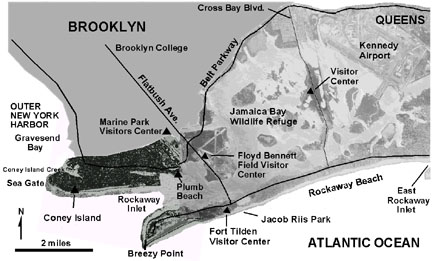

70. Jamaica Bay (Gateway National Recreation Area)

Jamaica Bay is a 10,000 acre wildlife refuge that straddles the boundary between Brooklyn and Queens (Figure 187). The refuge encompasses a diverse ecosystem of salt marshes and wetlands, tidal creeks, beaches and islands isolated within the shallow bay. The turbid waters of the bay are rich in algae and zooplankton, providing the base of the food web for invertebrates, brooding and feeding grounds for an abundant variety of fish. The salt marsh islands that cover much of the bay is a major feeding and resting point for migratory birds along the Atlantic Coast. This large tract of land and sea supports a large fishing community, and serves as a major multi-purpose recreational site for the metropolitan area.

|

| Figure 187. Map of Jamaica Bay, Coney Island, Rockaway Spit (Brooklyn and Queens). |

Jamaica Bay's history includes a succession "improvements." Until the late 1800s Jamaica Bay was essentially a wilderness area, serving a prosperous shellfish and fishing industry. In 1878, the Secretary of War along with the city government of New York petitioned to establish the bay as a major seaport. As a result, a major landscape modification project began. Broad channels were dug; the dredging spoils were used to fill in marsh areas and to create raised lands for dockage and piers. A large amount of marshland vanished in the construction of Floyd Bennett Field and Idlewyld (now John F. Kennedy International Airport). The Marine Parkway Bridge which connected Flatbush Avenue to the Rockaways was completed in 1937, hastening the development of the barrier island. Along the north shore of the bay, large tracts of wetlands and salt marshes were filled in to make space for subdivisions. Large landfills and sewage sludge disposal sites took away additional marshland and progressively contributed to the decline of the bay, both in extent and ecosystem quality.

Efforts to preserve the bay were ineffective until 1938 when Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and Parks Commissioner Robert Moses collaborated on efforts to protect it. In 1948 the lands were transferred to the New York City Department of Parks. Still, construction and "improvement" projects continued. Under Robert Moses' plan, the Belt Parkway was built around the north shore of the bay. Thinking that freshwater environments better served the wildlife, two great impoundments were constructed as part of a plan that ran the combined A and S train line across Jamaica Bay. Unfortunately, it wasn't until the 1960s that the true ecological value of the salt marshes was realized. However, by then the original extent of the Jamaica Bay salt marsh and surrounding freshwater wetlands had diminished from around 25,000 acres to about 13,000 acres. Although great strides have been made to protect the bay it is still under constant threat. Of perhaps greatest concern is the ever increasing influx of freshwater from treated wastewater and urban runoff that eventually enters the bay from numerous sources. Freshwater should also be considered a "pollutant" to the salt marsh habitat, in that marine and brackish water organisms have a low end tolerance level, beyond which they cannot survive or out-compete with freshwater plant species. Mosquitoes also favor freshwater. For instance, the tall reed grass that lines much of the Belt Parkway is not a native species! Before the massive volume of treated waste water began to flood portions of the bay, relatively little freshwater naturally entered the estuary, especially during the late summer and fall.

|

| Figure 188. Peat exposed by beach erosion at low tide at Floyd Bennett Field. Note the new marsh grass growth about a meter above the high tide line. |

However, the bay is being saved "indirectly" by other means. First, sea level is rising. This is quite evident in beach areas along the shore of the bay where erosion is exposing multiple levels of marsh peat layers (Figure 188). These layers indicate that sea level has risen as much as a meter within 100 years, however this measure is relative, and doesn't account for the compaction of the underlying sediments. Secondly, the dredging of the channels (deemed as so harmful in the past) are actually providing more efficient marine water flushing of the bay. This is especially important considering the amount of progradation of Breezy Point, and the obstruction created by the landfill created for Floyd Bennett Field. Had it not been for the construction of the groins and jetty at Breezy Point, and the episodic dredging of the shipping channel through Rockaway Inlet, Jamaica Bay as a saltwater marshland might perhaps be "dead" already!

The heavy buildup of the Rockaway barrier island is perhaps a recipe for disaster in the event of a hurricane. Coastal residents and city planners should take a look northward at islands in Jamaica Bay. These islands are, in part, a reflection of the natural geologic processes associated with the evolution of barrier islands and lagoons. The sand that forms the core of these islands was originally derived from the outwash the Wisconsin glacier. A much larger "ancestral" Jamaica Bay is recorded by the presence of the Gardeners Clay throughout portions of the south shore of Long Island, including the region of modern Jamaica Bay. As the Wisconsin glacier melted, sea level competed with isostatic rebound, creating an uneven record of marine transgression and regression throughout the New York region in Late Pleistocene and Holocene times. The islands in Jamaica Bay are likely reminders of devastating coastal storms that ripped through the barrier island, creating inlets with large tidal deltas. Longshore drift, storm event erosion and deposition, and the twice-a-day scour of tides are the natural processes that closed these inlets and created new ones. These islands are preserve stabilizing overgrowth of the salt marshes around their shores and the maritime shrub forests in the upland areas.

Jamaica Bay became part of Gateway National Recreation Area in 1974. Most of the area includes inaccessible wildlife habitat and is off limits except for educational and research purposes. Primary access points and educational resource sites include the Jamaica Bay Visitor Center on Cross Bay Boulevard, the Park Headquarters and Visitor Center at Floyd Bennett Field, and a new environmental education facility in Marine Park, Brooklyn.

| Return to Our Transient Coastal Environment. |